![]()

Prepared for

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

ABN: 18 108 001 191 2

Heritage Management Plan – Volume 2

Kirribilli House and Garden, Kirribilli, NSW

13-Nov-2023

Kirribilli House HMP Update

Doc No. FINAL

![]()

Prepared for

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

ABN: 18 108 001 191 2

Heritage Management Plan – Volume 2

Kirribilli House and Garden, Kirribilli, NSW

13-Nov-2023

Kirribilli House HMP Update

Doc No. FINAL

Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, NSW

Client: The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

ABN: 18 108 001 191 2

13-Nov-2023

AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to ISO9001, ISO14001 and ISO45001.

© (AECOM). All rights reserved.

AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. Subject to the above conditions, this document may be transmitted, reproduced or disseminated only in its entirety.

Document | Heritage Management Plan - Volume 2 |

Ref | l:\secure\groups\!env\team_iap\archaeology & heritage\proposals & projects without apic numbers\2023_05_10 kirribilli hmp\third draft hmp 20231113 public version\updated 2025\20250131 kirribilli house hmp vol 2 draft.docx |

Date | 13-Nov-2023 |

Originator | Redacted for public exhibition |

Checker/s | Redacted for public exhibition |

Verifier/s | Redacted for public exhibition |

Revision Date | Details | Approved | ||

Name/Position | Signature | |||

A | 20-Jun-2023 | Draft | Redacted for public exhibition |

|

B | 18-Oct-2023 | Draft | Redacted for public exhibition |

|

C | 13-Nov-2023 | Final | Redacted for public exhibition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

This document includes professional services that require approval from a registered professional.

Discipline / | Name of Registered Professional* | Signature | Registration No. | Date | |

NSW Board of Architects | Heritage | Redacted for public exhibition |

| Redacted for public exhibition | 21/06/2023 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* The registered professional must be the originator of this work or have provided direct supervision to the originator.

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

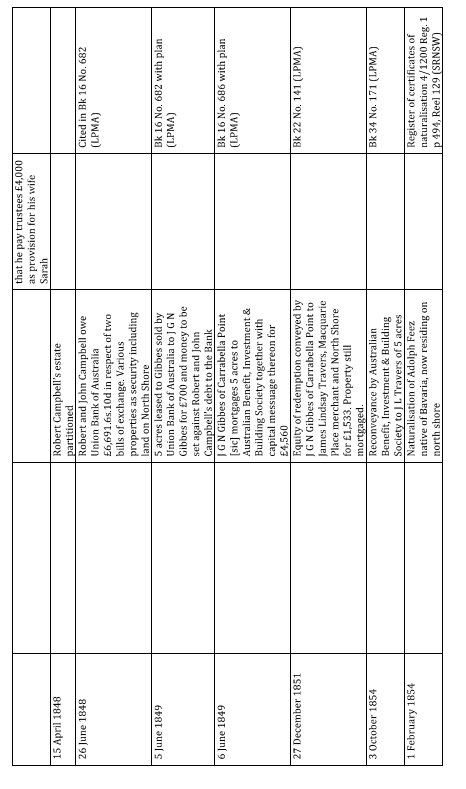

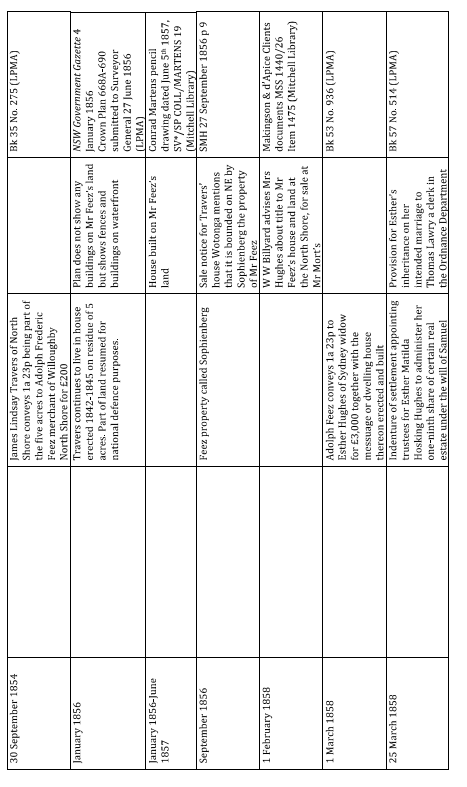

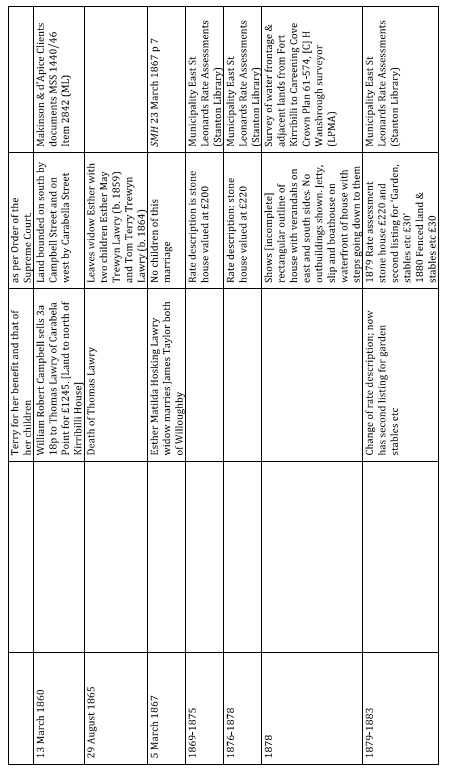

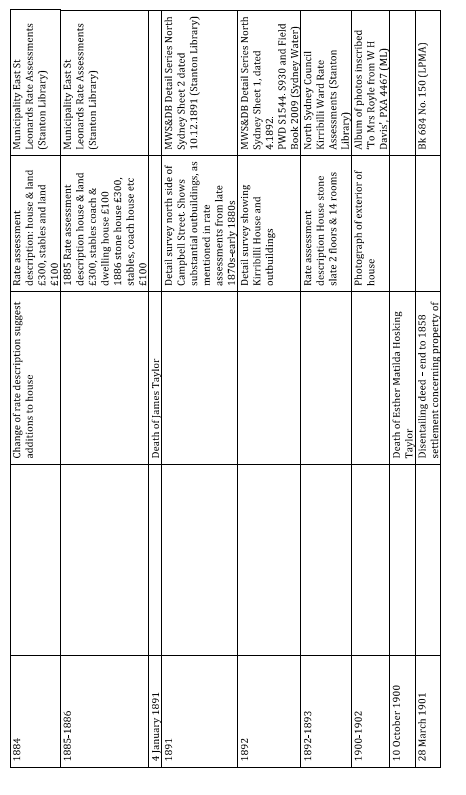

Historical Background

APPENDIX C

Australian Prime Ministers 1901

APPENDIX D

Historical Summaries

APPENDIX E

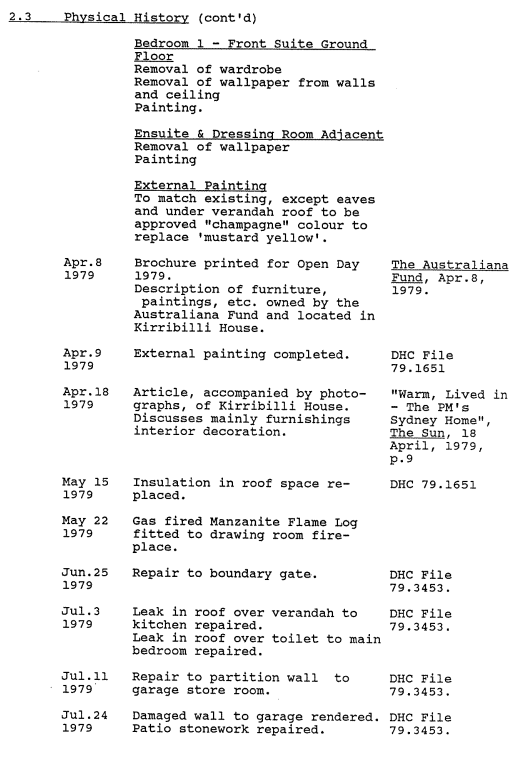

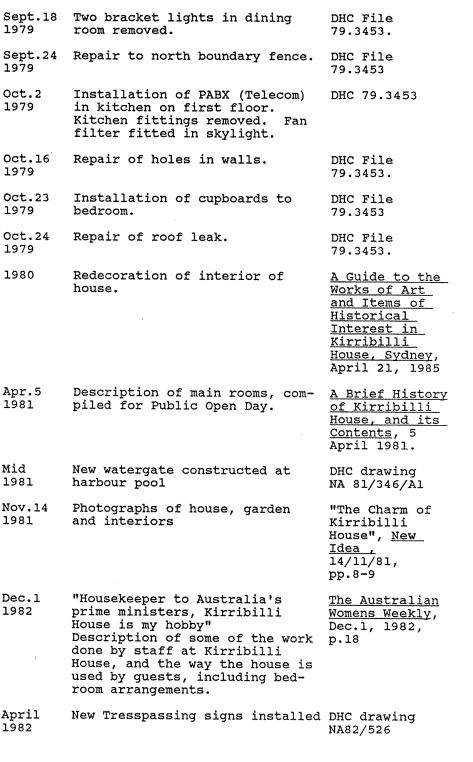

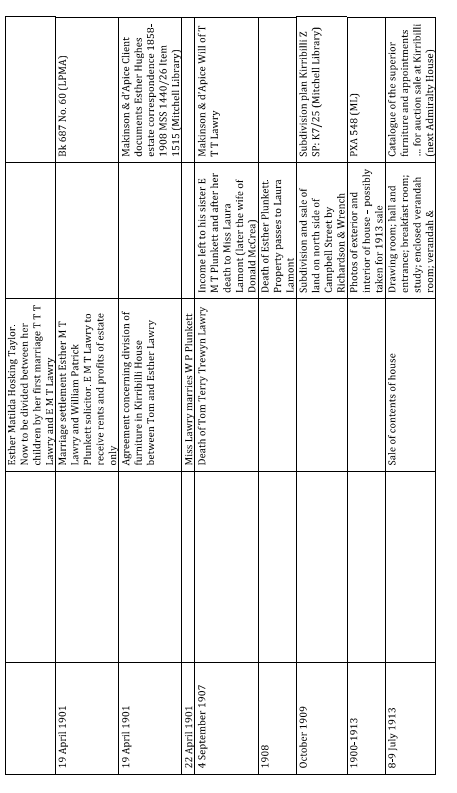

Timeline -1794 – 1957 by Rosemary Annable

APPENDIX F

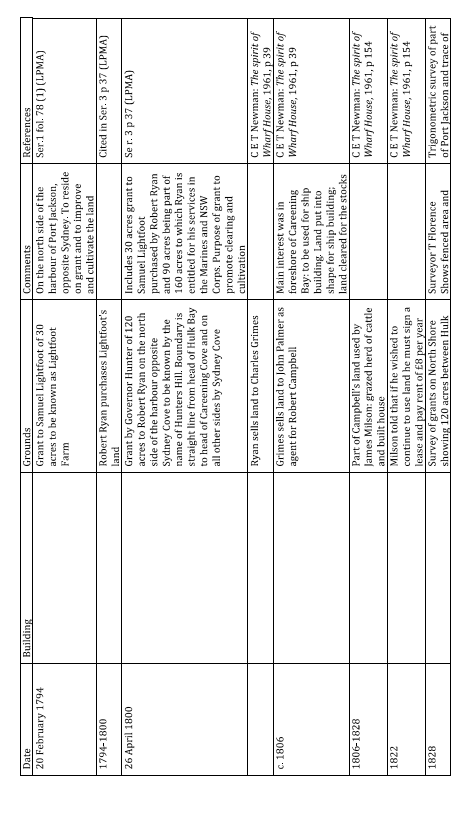

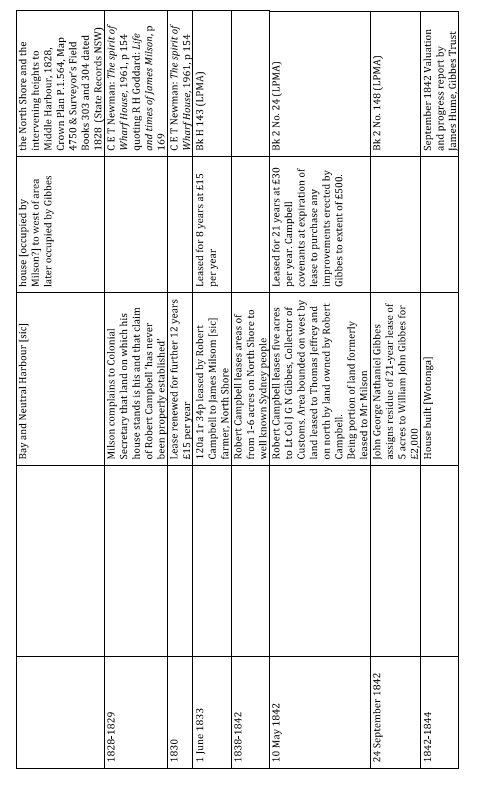

Owners and occupiers 1806 – 2023

APPENDIX G

Recent schedule of works 1978 – 2023

APPENDIX H

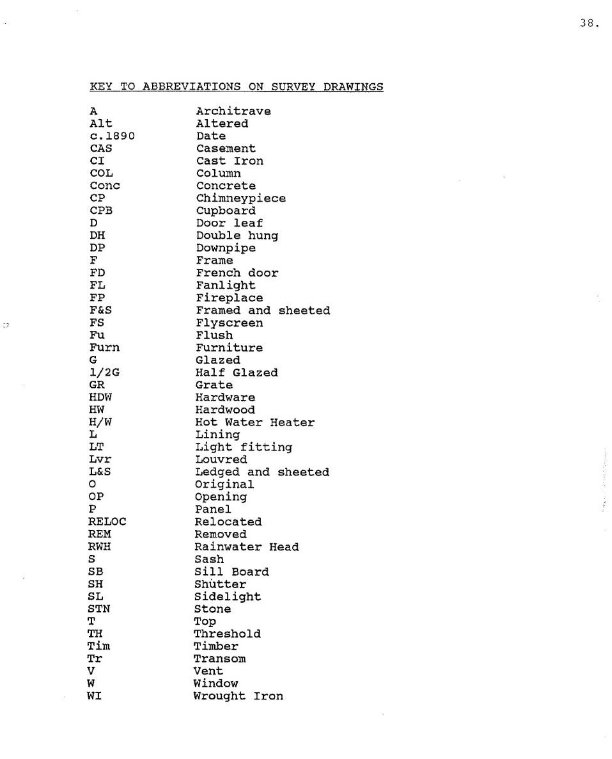

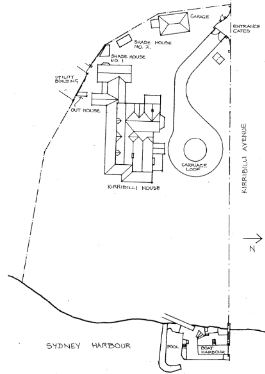

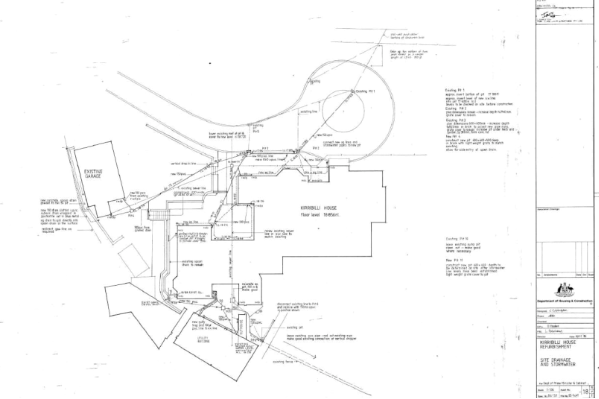

Physical survey/Fabric survey – Kirribilli House

APPENDIX I

Tree Survey by AECOM, 2023

APPENDIX J

Assessment of Indigenous Heritage Values by AECOM, 2023

APPENDIX K

Landscape Management Plan by Taylor Brammer, 2020

APPENDIX L

Non-Indigenous Archaeological Assessment by Casey & Lowe, 2010

APPENDIX M

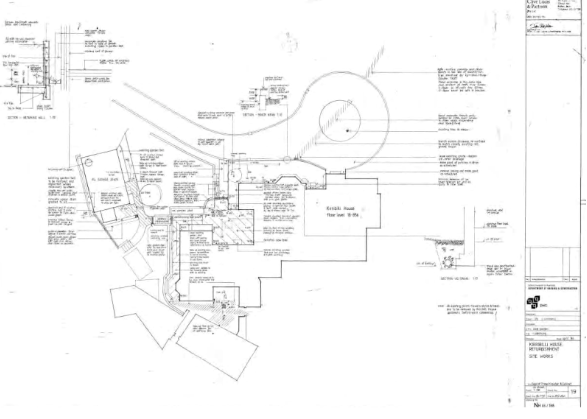

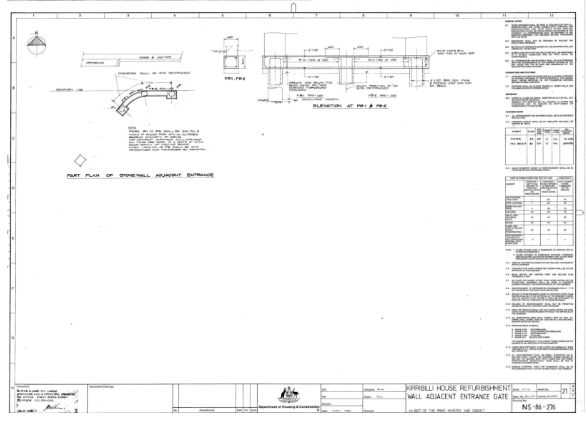

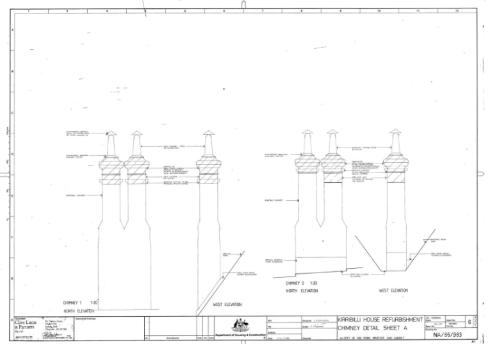

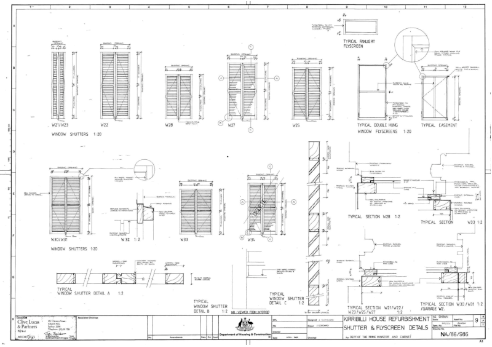

Evolution plans, by Design 5, 2010

APPENDIX N

Kirribilli Bathing Pool by Grace Karskens, 1987

APPENDIX O

Colour palette and interior design by GML, 2014

APPENDIX P

Heritage Induction Training Materials (Including Dos and Don’t Handbook), AECOM, 2023

Appendix Q

Assessment of NSW State Heritage and National Heritage assessment criteria

The historical background of Kirribilli House has been thoroughly researched by previous assessments. A chronological history was undertaken by Dr Grace Karskens, Catherine Forbes and Brendan Lennard as part of the “Kirribilli House, Conservation Analysis and Draft Conservation Policy” (November 1985), prepared by Clive Lucas & Partners. In addition, consultant historian, Dr Rosemary Annable, conducted additional research on the early European history of the site for the draft CMP in 2010 by Design 5 Architects.

The following historical background is based on Dr Annable’s research as presented in Appendix B2 of GML Heritage’s 2016 HMP. Dr Annable’s reports are included in Appendices E-G. AECOM findings from additional research has also been included.

Both Dr Annable and GML Heritage list the sources of documentary evidence used in their reports. In updating this report, where possible, documentary sources used in previous reports such as photographs, drawings, maps, and plans, have been verified/augmented from the following documentary sources:

The following history of the place was prepared by Dr Rosemary Annable as part of the historical research carried out for the Design 5 Architects 2010 draft HMP and was reproduced in the 2016 GML Heritage HMP. The text has been reviewed by AECOM and updated for any errors or omissions and knowledge gaps.

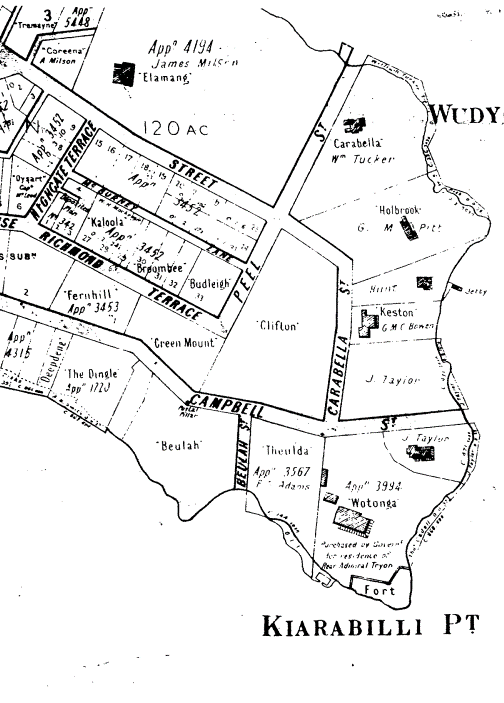

Within a few years of European settlement at Sydney Cove small grants of land were being taken up on the opposite side of the harbour at what became known as the North Shore. In 1800, Robert Ryan was granted 120 acres by Governor Hunter between the head of Hulk Bay and the head of Careening Cove, an area that incorporated an early grant to Samuel Lightfoot made in 1794.[1]

By 1806, Ryan’s land had been acquired by Robert Campbell who saw the area as a useful adjunct to his ship-building and mercantile interests at Sydney Cove and it remained in Campbell’s ownership for the next forty years until his death in 1846.[2]

Campbell’s first tenant was James Milsom, who built a house and ran a small farm and was, for some twenty years, the main occupant of the area.[3] From the late 1830s, however, as the property became more valuable for residential use than for farming or ship building, Robert Campbell began to lease parts of his land on the North Shore in smaller portions of a few acres. Many of these had desirable harbour frontages that not only provided views but also the easiest means of accessing the sites, by water.

In May 1842, Campbell leased five acres with a water frontage to Lieutenant Colonel John George Nathaniel Gibbes, Collector of Customs, for a period of twenty-one years, with the promise of the payment by Campbell of up to £500 at the end of that period (subsequently increased to £800) for any improvements made by Gibbes.[4] It was here at ‘Carrabella (Kirribilli) Point’, that Gibbes built the house that he called “Watonga”, later to become Admiralty House (Figure 1‑1).

Figure 1‑1: ‘“Wattonga” J LTravers Esq., Sept. 1855’, Rebecca Martens (Source: State Library of NSW, Call numbers DL PX 37/5)

Between 1830 and 1870s, the North Shore area was a popular location for residential development. The number of free settlers and emancipists were growing and access to the North Shore was limited to those who could employ licensed watermen and have access to their own boats and landing. The residents of the North Shore could enjoy the clean air, seclusion and harbour views and were protected from the crowds of the Sydney town. Residential development began in Neutral Bay in the early 1830s with ‘Craignathan’ ‘Thrupps cottage’ and Clee Villa’. In the 1850s houses included ‘Wallaringa’ (W. Dymock), ‘The Monastery’ (R.P Abbott), ‘Kurrabba House’ (Mr Jarrett), ‘The Dingle’ (Mr Grundy) and ‘Euroka/Graythwaite’ (Edwin Sayer). Houses on Kirribilli Point in the 1850s and 1860s included ‘Sunnyside/Wyreepi’ (Robert Hunt, Deputy Master for the Royal Mint), ‘Holbrook’ (Mr G M Pitt, of Pitt, son and Badgery). ‘Greenmount’ (William Tucker, wine merchant) and ‘Woodlands/Theluda’ ( H. H. Beauchamp) (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 1993:32-22).

Gibbes’ financial affairs became precarious later in the 1840s[5] as did those of Robert Campbell’s heirs, his sons Robert and John, who had to offer the five acres that their father had leased to Gibbes as security to the Union Bank of Australia to cover two bills of exchange. When the bank needed payment in June 1849, it sold the land to the lessee and occupant, J G N Gibbes (Figure 1‑2) for £700 to set against Robert and John Campbell’s debt.[6] After acquiring the title to his house and land at modest cost, Gibbes immediately mortgaged the property and eventually sold it, still mortgaged, to James Lindsay Travers (a merchant) in December 1851.[7]

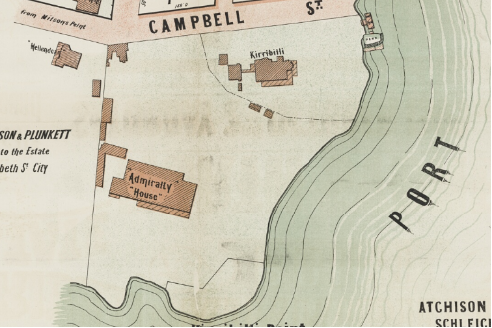

Figure 1‑2: Detail of 1840s map, “Campbell’s Estate”, showing the land leased to Lt Col Gibbes, and the outline of “Wattonga” (marked on map as ‘New House”) (Source: Trove, Ferguson Rare Map Collection, Map F 903)

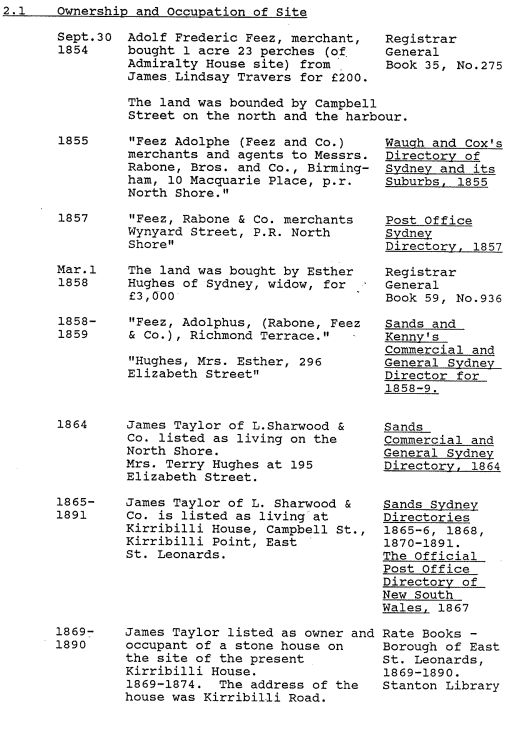

In September 1854, Travers sold 1 acre and 23 perches of land at the north-east corner of his Carrabella Point estate to fellow merchant Adolph Frederic Feez for £200.[8] A native of the Kingdom of Bavaria, Feez had arrived in Sydney in 1851 and in February 1854, then aged 28, had become a naturalised citizen, making him eligible to hold freehold land in the Colony.[9] He and Travers shared the same business address at 10 Macquarie Place in Sydney and had presumably become acquainted through mercantile interests.[10]

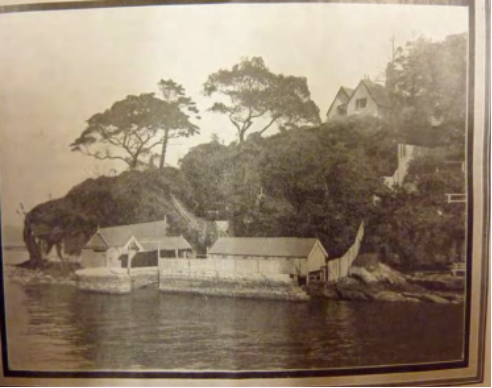

Feez named the property ‘Sophienberg’ and between September 1854 and mid-1857 built a house, although the exact date is not known. Plans of Travers’ property drawn in June 1856 describe the area as “Mr Feez’s land” and how only fencing, a jetty and other structures on the waterfront, but no buildings, suggesting that construction had not yet begun.[11] The top of the house is visible, however, above Wotonga, in a sketch by Conrad Marten of Kirribilli Point viewed from the south side of the harbour, dated 5 June 1857.[12]

Access by water was essential for these properties and the construction of a jetty and boat house would have been a prerequisite for any occupation, including landing materials for building. Adolph Feez was already living on the North Shore when he purchased the land in 1854 and it is possible that this was intended as an investment property rather than to provide him with his own home.[13]

The boat harbour, boatshed and bathing pool in particular also reflects the recreational activities that were popular at the time and reflects the historical theme of The Pleasures of the People-Society, Culture and Entertainment identified in the thematic histories of the North Shore (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 1993:125)

B-3.5 The Lawry/Taylor Family Home 1858-1908

Early in 1858 Mr Feez’s property, now complete with house, was put up for sale and on 1 March 1858 was purchased by Mrs Esther Hughes, widow of John Terry Hughes, for £3,000.[14] It seems likely that Mrs Hughes was purchasing the house for her daughter, Esther Matilda Hosking Hughes, in anticipation of her intended marriage to Thomas Lawry. Esther was underage when she married and while Mr Lawry was a clerk in the Ordnance Department on a salary of £450 a year, Esther had considerable property in her own right, bequeathed to her by her grandfather Samuel Terry.[15] With the permission of the Equity Court, Esther’s inheritance was the subject of a settlement formalised on 25 Mach 1858, the day of her marriage to Thomas Lawry. Under the terms of this settlement, the income from these properties was held by trustees for Esther and for any children of her marriage.[16]

From 1858 until 1908 the property that Adolph Feez had named Sophienberg, and later known as Kirribilli and Kirribilli House, was held in trust for Esther Matilda Hosking Hughes and her children and was their family home. Esther was married twice: first to Thomas Lawry, from 1858 until his death in August 1865 and, after a comparatively short widowhood, to James Taylor of the firm of L Sharwood & Co., importers, from March 1867 until his death in 1891.[17]

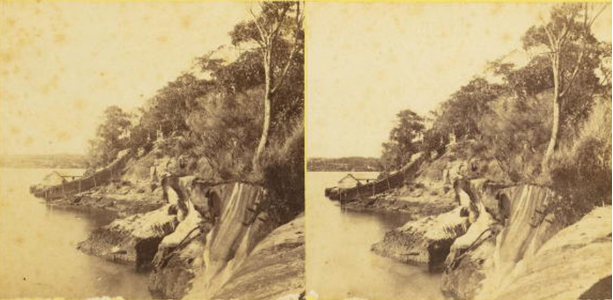

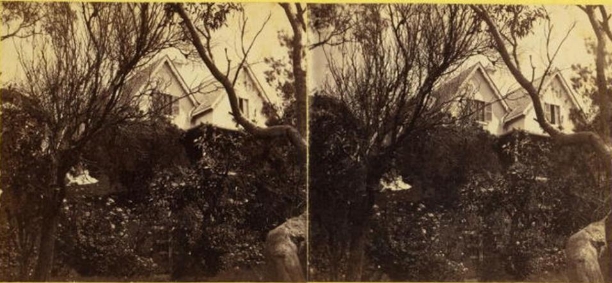

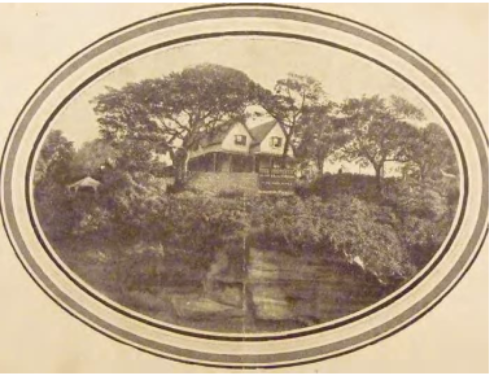

Esther and Thomas Lawry had two children, Esther Mary Trewyn Lawry born in December 1859 and Thomas Terry Trewyn Lawry born in March 1864.[18] Two stereo photographs, taken by William Hetzer in the period 1858-1863 show the harbour foreshore of Sophienberg and part of its gardens and grounds.[19] If the man, woman and child in the photograph of the house and garden are a family group, as seems likely, then this must be Thomas and Esther Lawry and their young daughter Esther (Figure 1‑3).

Figure 1‑3: One half of stereographic photograph of Kirribilli House & Garden, by William Hetzer, c. 1860-1863. A man, woman and child can be seen sitting on the grass behind a tree at left (Source: Powerhouse Museum, Call number 87/1019-15)

In 1860, Thomas Lawry purchased another piece of Campbell property, an area of 3 acres, 18 perches, immediately to the north of Sophienberg, on the northern side of Campbell Street. This land, bounded on the west by Carabella Street, added considerably to the family’s waterfront holdings and was separated from the family home only by the line of Campbell Street, which at this date seems to have been a street in name only.

Thomas Lawry ‘of Sophienberg, North Shore’ died in August 1865 aged 44 at his mother-in-law’s home, Albion House.[20] He had become a Justice of the Peace and Magistrate and by the time of his death, had relinquished his employment at the Ordnance Department.

It is not clear from street directories (the only source of information about place of residence at this date) whether Esther Lawry continued to live at Sophienberg after she was widowed, although she definitely lived in the area. Her future husband, James Taylor, was listed as resident at Kirribilli House in 1865 and 1866 and it is possible that the house was leased to him. What is evident is that Esther Lawry and James Taylor were neighbours at this period and that following their marriage, Kirribilli House was again Esther Lawry’s (Esther Taylor’s) home after their marriage in March 1867.[21] By this time the name Sophienberg had ceased to be used and the property was variously listed in street directories as Kirribilli House or just Kirribilli.

The marriage of James and Esther Taylor produced no children. Thomas Lawry’s children were aged three and seven when their mother remarried but they did not take their stepfather’s name of Taylor and retained the surname Lawry.

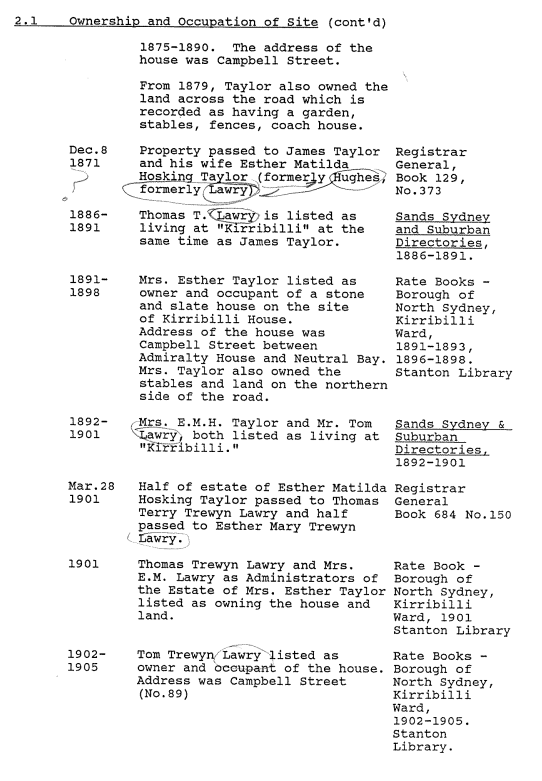

Evidence from the St Leonards Municipal rate books suggests two phases of change in the house and its ancillary buildings, in 1878-1879 and in 1883-1884.[22] In 1878-1879 buildings were erected on the land to the north of the house that Thomas Lawry had purchased in 1860. This was not separately itemised and rated at £30 as ‘Garden, stables etc.’ or ‘Fenced land, stables, etc.’ The 1891 detail survey shows three substantial structures on the land, two of them close to the entrance to the property which was directly opposite the entrance to Kirribilli House.[23]

A change in the assessed value of the house from £220 to £300 in the period from 1883-1884, suggests a substantial addition to the domestic accommodation. By this date, the two Lawry children were adults but unmarried and it is possible that this addition was to provide appropriate room for two more adults. As an unmarried daughter, Esther no doubt continued to live permanently at home and while her brother Tom had a property at Vermont, Cobbity, his keen interest in ‘aquatics’ no doubt saw him making good use of the boat houses and jetty at Kirribilli House.[24]

The extent of the house is shown in the 1891 survey and in the rate books is variously described as having 13 or 14 rooms. Following the death of her husband, James, in 1891, Esther Taylor continued to live at Kirribilli until her own death in 1900.[25]

Figure 1‑4: Detail of Parish of Willoughby map, c. 1899 showing Kirribilli as “Kiarabilli Point”. Location of Kirribilli House and grounds is marked in red (Historical Land Records Viewer, File Name 14019101.jp2)

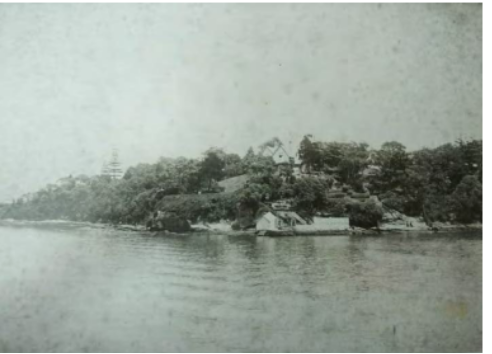

In 1901 her children, Thomas and Esther Lawry, agreed to divide between them the property that was held in trust for them according to their mother’s marriage settlement, including the properties at Kirribilli. Tom took the house and Esther the land on the north side of Campbell Street that their father had purchased in 1860.[26] In the same year, Esther, then aged 42, married William Plunkett and moved to her own marital home. A photograph of Kirribilli taken by W H Davis between 1900 and 1902 shows the house and possibly its occupant, Tom Lawry, perhaps with members of his household.[27]

Tom, who never married, continued to live in the family home until his death in September 1907 aged 42. It seems he had continued to have an interest in ‘aquatics’; he bequeathed his boats and motor launches to his friends.[28] His sister, Mrs Plunkett, died the following year, aged 49, ending the fifty-year association of the Lawry/Taylor family with Kirribilli House. In 1909 her land, on the north side of Campbell Street, was subdivided and sold, thereby separated from the Kirribilli House property.

According to the terms of Tom Lawry’s will, the major beneficiary following his sister Esther’s death was Miss Laura Lamont (Lamotte) who inherited a life interest in his furniture and effects, an income from his properties and a life tenancy of Kirribilli House.[29] Laura initially lived at Kirribilli House, which she rented at a nominal rent agreed to by the trustees and it became her marital home following her marriage in 1909 to William Donald McCrea.

Figure 1‑5: Detail of subdivision map for the Kirribilli Estate, c. 1909 showing Kirribilli House (Source: State Library of NSW, Call number Z/SP/K7, SP/K7).

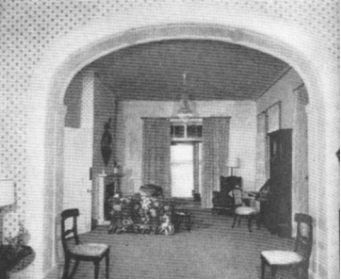

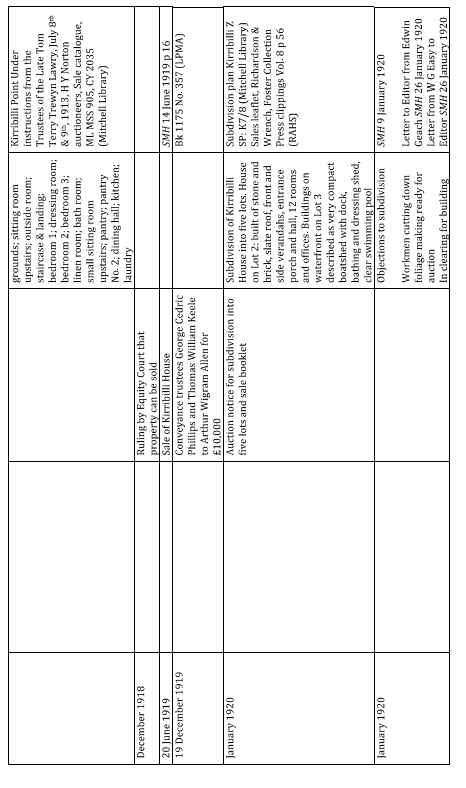

By 1913, however, she wished to move, and the trustees of the Lawry estate petitioned the Equity Court to allow them to let the house for a reasonable length of time, to obtain a tenant. The petition was not supported by Mrs McCrea and so her life interest prevailed, and the petition was disallowed by the Court.[30] Meanwhile, Laura and her husband vacated Kirribilli House anyway. The contents of the house were auctioned in July 1913, and the house was then tenanted, presumably on short-term leases.[31] An album of photographs of both interior and exterior views of the house at this period may have been taken for the purposes of the auction.[32]

Following the departure of Laura and William McCrea, the house was occupied by Arthur Pittar, a dentist (listed in Sands Directory in 1915-1918) followed by Michael Minnett (listed in Sands Directory in 1919 and 1920), the head gardener at Admiralty House. Sands Directory (which was frequently out of date) may have been incorrect about the length of Minnett’s occupancy as the house had not been occupied for some time and was “…in a very dilapidated state” when it went for auction in January 1920.[33]

In 1918, another suit in the Equity Court was more successful, when Laura McCrea petitioned to sell the Lawry trust properties including Kirribilli, which by now was costing more in upkeep than it raised in rent.[34] The sale was ordered by the Court in December 1918 and in June 1919 Kirribilli House was sold to A W Allen for £10,000. The property was advertised as having an unequalled position on the harbour front for “…a site for a large residence, for flats, or public buildings, or would subdivide to advantage”.[35]

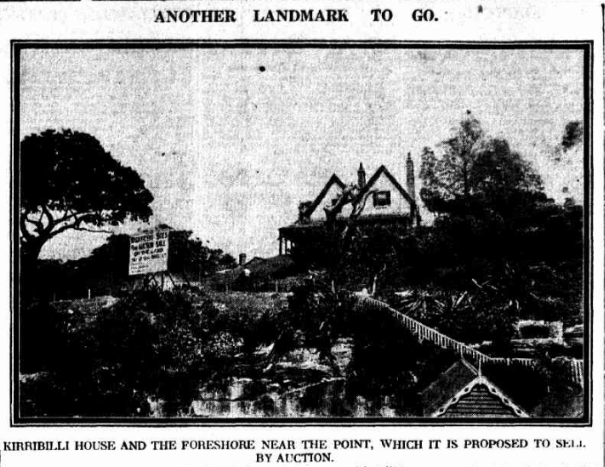

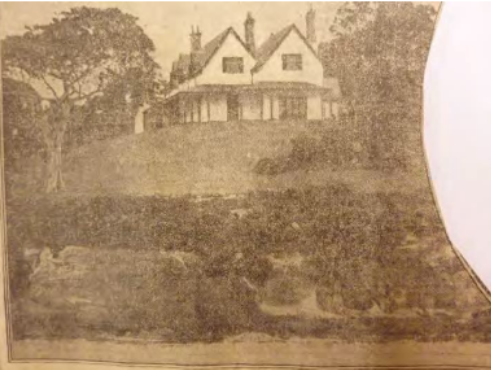

Allen’s purchase had been purely an investment and six months later the house and land were again offered for sale, this time divided into five lots (Figure 1‑6) .[36] The site was indeed a very desirable one, and it seemed that the house would inevitably be demolished. Photographs of the apparently intact house and garden in the sale brochure contrasted with those in the newspapers, which showed that tree felling had already begun in advance of the auction,[37] increasing public concern that that the site was to be cleared for the construction of residential flats.[38] An inscription “H L M 1820” was found on a large rock when clearing the land on the waterfront.[39]

Figure 1‑6: Kirribilli House Subdivision Plan, 1920 (State Library of New South Wales, Ref Z/SP/K7/8)

There was little comment on the historical value of the property, but opposition to the sale centred largely on it being the only remaining piece of waterfront land that could be useful for public purposes. Headed by the People’s Open Air Space Movement, there was much agitation for the retention of the site for public purposes, while a number of ‘public spirited persons’, including Senator Pratten, Dr Mary Booth, Mr Sydney Smith and the Mayor of North Sydney waited upon the Minister for the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook, to encourage him to place the matter before the Federal Government.[40] A few days later, a public meeting convened by Dr Mary Booth, decided to make a direct appeal to the Prime Minister.[41]

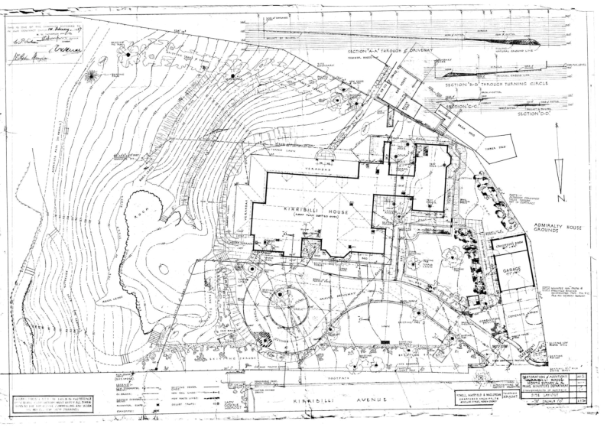

More pragmatically, from the government point of view, Admiralty House had been offered to the incoming Governor-General as his residence when in Sydney and its amenity and value would have been seriously eroded by the construction of flats so close by. While the public protests gained publicity, it seems that it was the latter arguments that had some weight with the government.

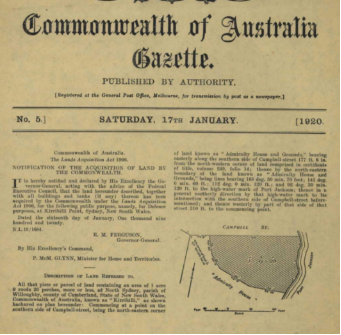

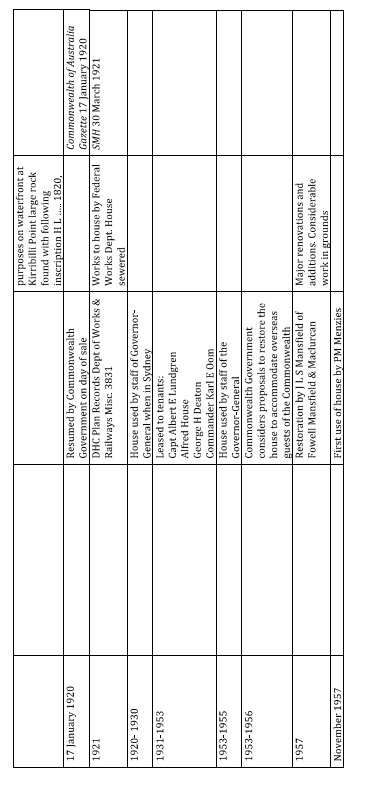

The acting Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Cook, agreed to the purchase of the house for £12,000 (the Valuer-General’s valuation)[42] and when the offer was rejected by the vendor,[43] the house and land were resumed by the Commonwealth on the day of the auction sale ‘for defence purposes’ (Figure 1‑7).[44] As Minister for the Navy, Cook had thought that Kirribilli House might replace Tresco as the home of the officer in charge of Garden Island. However, by December 1920, the Cabinet had decided that both Admiralty House and Kirribilli House would be placed at the disposal of the Governor-General when in Sydney.[45] When the repairs to Kirribilli House were complete and Lord Forster, the new Governor-General, found that there was not enough accommodation at Admiralty House for his married daughter, whose husband was on his staff, Kirribilli House was accordingly taken up as part of the vice-regal establishment and Tresco remained the home of the Admiral.[46]

Figure 1‑7: Gazette Notice of resumption, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 17 January 1920, p. 1

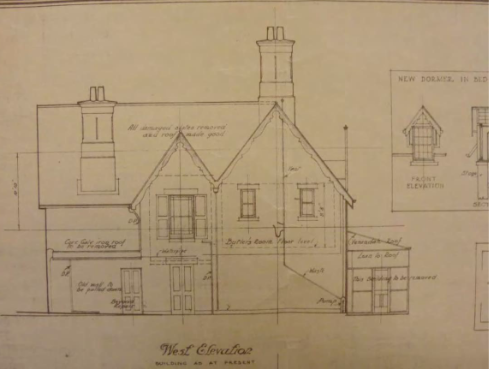

From 1920 until 1930, Kirribilli House was used in conjunction with Admiralty House, to provide accommodation for the Governor-General’s staff, and in particular for the aides-de-camp. Plans for alterations and additions to the house drawn in January 1921 provided for a small addition to the west end bringing most of the service areas indoors, accessed either from within the house or from the porch on the west side. On the ground floor an office was provided for the aides-de-camp, with adjacent conservatory, and a servants’ hall, with bedrooms for the staff upstairs at the west end of the house.[47] The house was fully sewered, an amenity that it had not previously enjoyed and the whole of the exterior was painted white to conceal the difference between the existing stonework and the new brick addition.[48]

These alterations and additions were carried out by the Works Director in Sydney for the Commonwealth Works and Railways Department, which was also responsible for the choice of soft furnishing. In 1922, the Afforestation Branch in Canberra provided trees for Kirribilli House, where it seems, the grounds were cared for by the Head Gardener of Admiralty House, Mr Minnett.[49]

Both Lord Forster (Governor-General 1920-1925) and Lord Stonehaven (1925-1931) had several aides-de-camp. It is not known whether the house was used permanently by an aide-de-camp based in Sydney, or only during vice-regal visits to Admiralty House. According to an article in the Cairns Post, Lord Stonehaven used Kirribilli House for visitors and he frequently slept there himself, in preference to Admiralty House.[50]

By 1920, the two boat houses on the foreshore and the canopy over the bathing area were described as ‘…more or less dilapidated”, but the bathing area, jetty and retaining walls were still in reasonable repair.[51] These remained unused in 1920-1930, as similar facilities at Admiralty House were sufficient and so deteriorated even further.

In 1930, at a time of extreme economic stringency, the Commonwealth government decided to discontinue the use of Admiralty House and Kirribilli House by the Governor-General and to lease Kirribilli House.[52] The contents of the house were sold by public auction in November 1930.[53] Figure 1‑8 shows the site during the construction of the Harbour Bridge.

Figure 1‑8: Admiralty House (left) and Kirribilli House (right) during construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, c. 1930 (Source: Sydney Morning Herald, 26 March 1930, p. 18)

In October 1930, tenders were invited for the lease of Kirribilli House and in December 1930 the house was leased to Captain Albert Edwin Lundgren CBE, a Swedish shipping agent, for 400 guineas per annum for a period of three years plus an option of renewal for a further two years.[54] Captain Lundgren surrendered the term of his lease in February 1935 to Alfred House and when this ended, the house was vacated.

The expiration of the lease coincided with the government’s decision in 1936 to make Admiralty House available for the incoming Governor-General, Lord Gowrie, but Kirribilli House was not included in this arrangement. Instead, the house was renovated and once again put up for lease. Tenders to use it as a boarding house were rejected. Instead, it would be leased ‘…to some person of means who would be able to afford the rent of a home in such a locality’. Improvements prior to leasing included the installation of a hot water system, modernising one of the bathrooms and the installation of a gas stove.[55]

The new lessee was George Henry Deaton, of Deaton & Spencer, printers, and the rent was.[56] The grounds were ‘very neglected’ with many dead trees and shrubs. The flower borders were a mass of weedy growth, most of the grassed areas were Buffalo grass and the gravelled approach was also overgrown.[57] In 1939, damp was a problem. The cellar was full of water and expensive wallpaper was becoming discoloured and coming off the walls. Despite this, Mr Deaton was not keen to relinquish his lease and caused some embarrassment to the government when he refused to do so when preliminary discussions were in progress concerning accommodation for the Governor-General designate, HRH the Duke of Kent.[58]

In correspondence with the Australian government, concern had been expressed by the royal household about Kirribilli House being tenanted, but Mr Deaton was adamant that he would not move; and there was no provision for breaking the lease. With the outbreak of war late in 1939, the Duke of Kent did not take up the position of Governor-General and the problem was solved. Mr Deaton’s lack of co-operation may, however, have worked against him when he asked to surrender the lease in 1942 and was refused. With a sick wife and unable to secure any domestic help, Mr Deaton closed up the house in February 1942 and moved elsewhere. It was used for a month by the military, but then remained unoccupied until October 1943, when Mr Deaton transferred his lease to Commander Karl Erik Oom. A Naval officer and noted hydrographer, Commander Oom had recently been appointed officer-in-charge of the Hydrographic Branch in Sydney, responsible for survey operations in the South-West Pacific for which he won international recognition.[59] He continued to live at Kirribilli House until October 1953, by which time he had been invalided from the Navy.[60]

With Kirribilli House once more vacant, the question of its future use came under discussion. The Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was reluctant to dispose of it and felt that any action to do so, ‘would meet with general disapproval particularly in New South Wales’. Moreover, the same arguments for its retention applied as in 1920, because when invited to be Governor-General, Sir William Slim had been told that Admiralty House would be made available to him. If Kirribilli House was sold, the land subdivided and flats built, then this would destroy the privacy of Admiralty House, and ‘…detract greatly from its value”.[61]

For their part, although Kirribilli House had not been made available for vice-regal use since 1930, success Governors-General had retained an interest in the house, had continued to ask (without success) for it to be made available for their personal or domestic staff and requested that they be kept informed of plans for its future.

In December 1953, M L Tyrell, official secretary to the Governor-General, wrote to the Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department informing him that Sir William Slim wished to obtain permanent use of Kirribilli House and had had discussions with the Prime Minister on the topic. As Admiralty House was to be used more frequently over relatively longer periods of time, it was necessary to send almost all members of the Governor-General’s staff to Sydney.[62] Indeed, three or four members of staff were already living temporarily at Kirribilli House (an arrangement that continued intermittently until July 1955).

Early in 1954, the Department of Works reported on the building and in August the Ceremonial and Hospitality Officer of the Prime Minister’s Department, J H Scholtens, personally inspected Kirribilli House. Scholtens’ report was not encouraging. The grounds were shockingly neglected, the shrubbery growing wild, the lawns overgrown, paths cracked and the whole area “…in the grip of nature”. The state of the house was “…in complete harmony with the grounds”. With no damp course, damp, dry rot and a lack of general maintenance, his overall impression was “…a dirty, decayed, damp dwelling deserving destruction”.[63]

The Department of Works gave an estimate of £6,650 for the necessary works and pointed out that the layout for the house was unsuitable for domestic staff accommodation. Their report offered, however, another perspective; that once completely renovated, the house would offer accommodation, “…of which the official staff would be highly covetous”.[64] By October 1954, it had been decided that the house did indeed offer possibilities and in March 1955 approval was given for a private architect be engaged to prepare proposals for alterations to the house for the government’s consideration.[65]

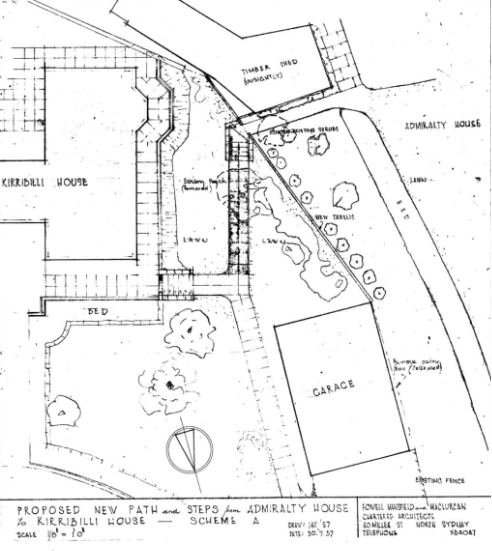

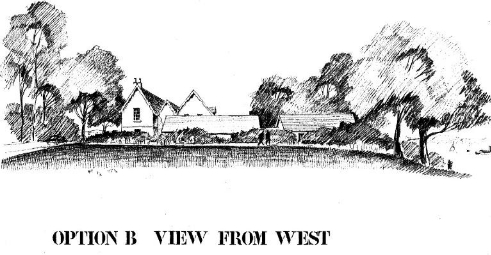

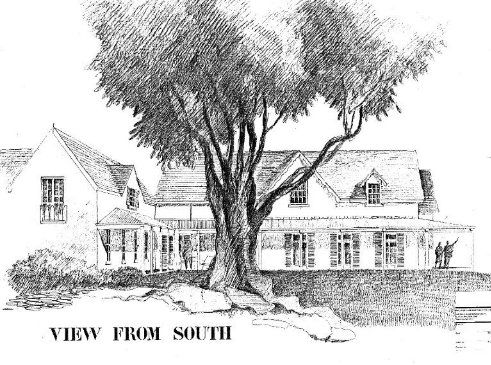

The NSW Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects was invited to submit a panel of names and Mr J C Fowell of Fowell, Mansfield and Maclurcan was recommended.[66] It was, however, his partner, J C Mansfield, who was to become the designer and supervising architect of the project. Fowell Mansfield and Maclurcan’s drawings and report on proposed renovations and additions to Kirribilli House was completed in September 1955.

In light of the government’s brief that Kirribilli House would be restored ‘…to provide accommodation from time to time for distinguished visitors and guests of the government’, Mansfield’s proposal was a scheme that would allow Kirribilli House to be used either as two separate flats, or, on special occasions, as a whole. The ground floor flat would be suitable for use by the Prime Minister on visits to Sydney or for distinguished visitors, and the other flat for guests separately, or as overflow accommodation for either Admiralty House or the ground floor. The house had ‘…some historic interest and architectural character occupying a superb site on the harbour foreshore’ and would have “…a charm, individuality and local colour which would be greatly appreciated”. Its decoration and furnishings should be chosen, Mansfield suggested, “…to create an atmosphere of quiet distinction”. The major change to the existing house would be the relocation of the stairs to provide privacy for each flat and, the main addition, a new service wing with kitchen, pantry and staff quarters, in the same style as the original building.[67]

In January 1956, following the re-election of the Menzies government for a third term, it was decided to ‘press on smartly’ with the rehabilitation of Kirribilli House.[68] Working drawings were completed in March to May[69] and furniture, carpets and curtains were removed from the house in anticipation of work beginning.[70]

As the house had not only been completed renovated but also decorated and furnished, Mansfield suggested that “…a lady of outstanding taste and furnishing expertise – known to the Prime Minister – not connected with any decorating firm but knows them all” might work with his firm to undertake this aspect of the work. The lady concerned was Helen Blaxland, who, “apart from her flair for decoration and knowledge of furniture”, was “thoroughly aware of all that is necessary and desirable in such a household”.[71] With the “enthusiastic and appreciative” support of the Prime Minister Menzies and his wife, Dame Pattie, this arrangement was approved.[72]

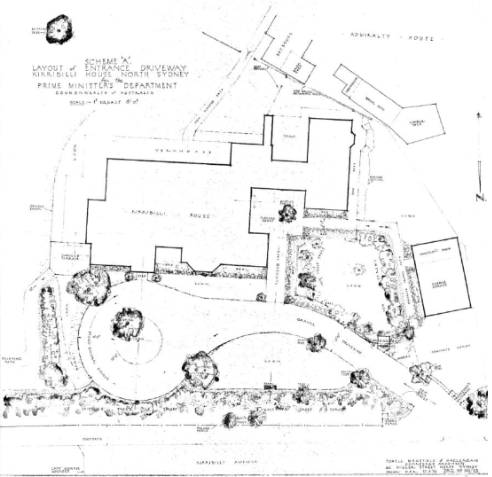

At the end of February, Mansfield submitted a summary of his ideas and proposals for the treatment of the grounds of Kirribilli House and the interior decoration and furnishing,[73] and in March the Executive Council approved the cost of the building contract. The Secretary to the Treasury was informed that the Governor-General and Prime Minister had agreed that Kirribilli House should be renovated as soon as possible and divided into two apartments to be used: by overseas guests of the Commonwealth; by certain of the Governor-General’s staff when at Admiralty House; and by the Prime Minister when in Sydney.[74]

Although the working drawings were prepared and finance approved, an increase in the estimates and general concern about costs delayed further action. In January 1957, Prime Minister Menzies finally gave his approval and in February the building contract with H W Thompson Pty Ltd was signed.[75]

Work on site took place between March and October 1957 and as it neared completion Kirribilli House was placed under the control of the Prime Minister’s Department.[76] The Department was keen that there be no doubt about who was in control of the house but trod carefully when dealing with the Governor-General’s request for his staff to occupy the top floor, trying to avoid a showdown.[77]

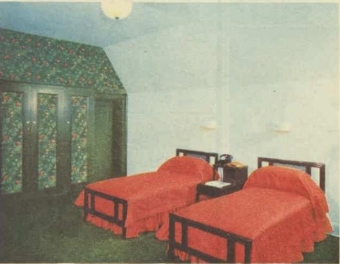

The philosophy for the interior decoration and furnishing of Kirribilli House was that the house “…would present the appearance that it had been lived in continuously, the taste of the original owners having been modified as the years went by, and modern comfort and vitality introduced”. It was this appearance that was affected by Helen Blaxland, working in particular with Marion Best Pty Ltd. The house included a mix of modern furniture and a few good antiques “…to establish the desired character”[78] some of which were purchased in Ireland where quality 18th century furniture could be purchased at extremely low prices.[79]

While economising on antiques, the carpets were specially woven and wallpapers specially printed. As Mansfield had suggested, the general ambience of the house was essentially that of an old colonial home.

In the grounds, Mansfield’s landscape plan was put into effect by the head gardener of Admiralty House, G W Gillham and his staff, with useful suggestions and advice on his planting plan by Professor L D Pryor, the Director of ACT Parks and Gardens.[80] The planting was in three sections: “the atmosphere of an early Australian garden with old-fashioned plants” near the house, exotic that would be of interest to overseas visitors; and on the lower slopes near the harbour, local flora.

The first official visitors were the Prime Minister and Dame Pattie Menzies and their staff, who signed the Visitors’ Book on 25 November 1957 and stayed for four days. The day after their departure the Prime Minister of Japan was the first overseas guest to use Kirribilli House, for an overnight stay.[81] In the four years since the Governor-General had indicated his wish that Kirribilli House be available permanently for his staff, there had been a shift in emphasis. The needs of the Prime Minister now came first and although the house was divided into two separate flats, the Prime Minister would enjoy exclusive use of them when in residence.

As Kirribilli House came into new life, the Prime Minister’s Department put on file the policy for the use of the house as approved by the Prime Minister. The house “…should play a ‘special occasion’ role and not develop into some sort of hotel”, but on the other hand it should not be under-used. In addition to its use for government guests from overseas and for the Prime Minister when in Sydney – and the use of the upstairs bedrooms by the Governor-General’s staff – Kirribilli House could also be made available to a limited number of distinguished overseas guests who were not government guests but who were on public business or private, non-commercial visits. In addition, Commonwealth government ministers might use the house for entertaining (but only for luncheons and early evening receptions) with the agreement of the Prime Minister.[82]

From 1957 until 1967 the running and management of the house was in the hands of a married couple, Mr and Mrs Ferry, who were the resident custodian and housekeeper. While Mrs Ferry filled the roles of housekeeper, cook and occasional hostess, her husband undertook a large range of jobs including repairs and maintenance in the house and substantial work in the grounds. In 1959 he was placed in sole charge of the gardens assisted by a contract gardener.[83] In November 1967, this work was overtaken by a new gardener, Mr R Kulper, qualified horticulturalist.[84]

Following its refurbishment in 1957, no substantial works were undertaken in the house for over twenty years, although parts were subject to campaigns of redecoration by Prime Ministers’ wives. Mrs Holt in 1966-1967 favoured chartreuse Thai silk wallpaper for the drawing room walls and ceiling, with similar colours in the dining room,[85] while her successor, Mrs Gorton, ordered wallpapers from the USA.[86] For the exterior, Mrs McMahon in 1972 wanted Kirribilli House to be painted white and black instead of the existing white and grey.[87] Mr Mansfield and his firm continued to be associated with the house, working with Mrs McMahon in 1972-1973 on small alterations in the hallways, until all work at Kirribilli House ceased on the election of a new Labor government.[88]

Early in 1976, under the new Fraser government, the policy for the use of Kirribilli House was reviewed. No visitor had been kept in the early years of the house’s use, but these had begun to be recorded from 1969-1970.[89] On the basis of these figures, there was a concern about the dwindling use of the house by distinguished visitors (for whom the accommodation was in many cases somewhat limited), which was down to less than three days a year. Meanwhile, use by successive Prime Ministers had varied considerably. Mr McMahon (1971-1972) had used the house only three times in 21 months, while it had been more popular with Mr Whitlam, who used it on 128 occasions in three years. In light of the change of government, it was recommended that the house be kept, without any change in policy on use, to see how things developed with the new Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser.[90]

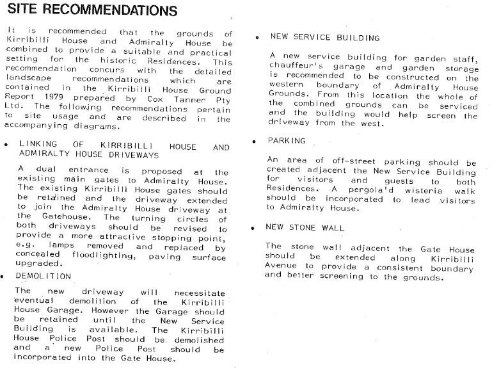

The ‘holding position’ recommended in January 1976 proved to be a wise position. In September, Prime Minister Fraser set up a committee to advise on the operation, conservation and long-term development of all four official residences of the Commonwealth, the first time that a unified approach had been taken on caring for these establishments. In its first report, the committee recommended that an Official Establishments Trust be established as a permanent, independent advisory body and this initiative was duly announced by the Prime Minister on 20 September 1979.

The first work undertaken at Kirribilli House under the guidance of the new Official Establishments Trust was the refurbishment and redecoration of the main bedroom. A décor “…in keeping with the historical significance of Kirribilli House” was adopted for this work, an acknowledgement of the changed nature of heritage conservation since the 1950s and an approach that did not depend exclusively upon the taste of the current Prime Minister’s wife for inspiration. The following year, the official reception areas on the ground floor were “…comprehensively refurbished and redecorated” and the main guest suite on the first floor was also refurbished.[91] Meanwhile, the Department of Housing and Construction began preparing a long-term plan of restoration.[92]

By this time, it was becoming apparent that major works were needed at Kirribilli House to combat problems such as rising damp, some of which had manifested itself quite soon after the 1957 work was completed. In 1985, Kirribilli House was the subject of extensive analysis and research by Clive Lucas and Partners whose conservation policy for Kirribilli House and recommended works were accepted by the Official Establishments Trust in 1985. The recommended restoration philosophy adopted by the Trust was that the front of the house be reconstructed and restored to its 1880s configuration and layout, “…this being the date of most significance to the architectural history of the house”. The 1950s alterations to the rear would remain with minimal rearrangement to enable the house to fulfil its current function.[93]

Due to funding constraints, these works were undertaken in a staged programme between 1985 and 1988. The most urgent included roof repairs and re-slating, the installation of a damp proof course and improved external drainage.[94] Interior refurbishment followed and David Spode was commissioned to prepare designs for internal decoration in the style of the 1880s, consistent with the conservation philosophy.[95]

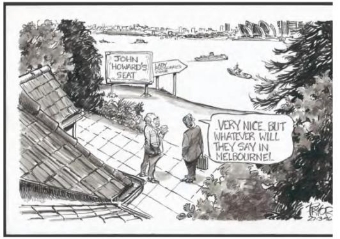

A substantial change to the role of Kirribilli House occurred in 1996 with the election of the Liberal/National Party Coalition under the leadership of John Howard. The new Prime Minister, who held the seat of Bennelong and whose family home was also in Sydney, soon made it clear that he would “…not spend quite as much time in Canberra” as some of his predecessors and that his family would not be relocating to The Lodge (the official Canberra residence of the Prime Minister). When it was found impossible to upgrade security at the family home in Wollstonecraft, Kirribilli House became the Howard family’s main home, the first time it had served this function since 1953.

During the Howard family’s residence, a proposal to relocate the 1880s staircase within the main hall, one of the recommendations of the 1985 Clive Lucas report, finally came to fruition. Not only was this part of the philosophy adopted for the house, but also with only a single occupant, there was no need for the separation between the ground and first floors that Mansfield had been at pains to provide for the use proposed in the 1950s.[96]

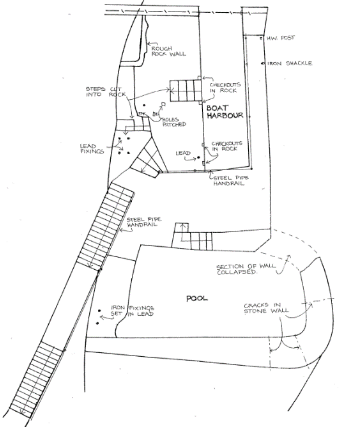

Despite its use as a family home, some of the once-favoured facilities of Kirribilli House were abandoned. In 1986, Grace Karskens had identified the Kirribilli House stone harbourside swimming pool (a part of its jetty and boat sheds complex) as “…probably the oldest bathing pool on Sydney Harbour”.[97] However, a report for the Official Establishments Trust in 1999-2000 recommended that the pool and adjacent boat dock be preserved only as ruins as any “residual heritage value” had been “…irrevocably diminished by substantial work undertaken in 1968” and that there was no prospect of a boat dock being used in the future.[98]

After eleven years as a family home, the role of Kirribilli House changed swiftly following the Labor election victory in 2007. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd confirmed that living in The Lodge was Labor party policy and that he would not be departing from that arrangement. In May 2008, the Prime Minister announced that Kirribilli House would be made available to up to ten registered charities a year, for fundraising purposes, a new departure for a government residence that had once been intended to place a “special occasion” role, for distinguished guests of the government.[99] This policy had begun to be implemented when Kevin Rudd was replaced as Prime Minister by his deputy, Julia Gillard in June 2010. Prime Minister Julia Gillard continued this arrangement until she was replaced by Kevin Rudd in June 2013.

Following the election of Tony Abbott as Prime Minister in September 2013, Kirribilli House became the primary residence of Abbott’s family while work on The Lodge was being undertaken. Between September 2013 and September 2015, Prime Minister Abbott resided between Kirribilli House and the Australian Federal Police Academy College while works to The Lodge continued.

In September 2015, Tony Abbott was deposed as party leader and Malcolm Turnbull became the new Prime Minister. With work on The Lodge complete, Prime Minister Turnbull confirmed that the Lodge will continue as the primary official residence of the Prime Minister, and that Kirribilli House will be used for official purposes of the office of the Prime Minister.

In 2022, the Australiana Fund compiled an illustrated care manual (The Australian Fund, 2022) for the collection of artwork, furniture, and memorabilia on loan for display at Kirribilli House.

This section (verbatim) was prepared by Geoffrey Britton in 2015 as part of the GML 2016 HMP to confirm and update Britton’s assessment that was completed as part of the Design 5 2010 HMP.

After many decades of development there remain persistent components of a much earlier, pre- European landscape within the Kirribilli House site. These can be summarised as underlying landform, remnant vegetation and the site’s ancient relationship with the drowned river valley that now forms Sydney Harbour.

Despite various earthworks—including nineteenth-century levelling for house benches and terracing of steeper areas—the basic site morphology remains largely consistent with that formed thousands of years ago. Obvious components include the dramatic sandstone cliffs at the eastern edge (mostly visible from marine craft within the harbour) and the massive line of outcropping running through the central part of the site to the northeast, east and southeast of the house.

Some of this latter feature has been covered by grass or obscured by the growth of garden plants. In other places the rock outcropping has been built over with steps (the access path near the southern boundary), or hidden by the recently installed large water tank. Prior to the water tank’s installation, the area behind it was a sandstone outcrop that provided an intimate, secluded space within the grounds contrasting with the open, expansive lawns nearby. It likely also afforded an excellent viewing prospect out to the harbour.

Persistent locally indigenous vegetation includes Port Jackson fig (Ficus rubiginosa)—at least one old specimen remained near the south eastern corner of the site throughout the nineteenth century and half of the twentieth century (it was removed by c1968). A specimen of this species survives near the main entry gates at Kirribilli Avenue and other seedlings remain along the eastern cliff line. Smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata) also remains on site and is evident in the archival record. Additional indigenous representatives on site include a few struggling trees under the large Hill’s fig tree, and another regenerating tree near the eastern cliff.

Other local species present include several coastal banksias (Banksia integrifolia), blueberry ash (Elaeocarpus reticulatus), sweet pittosporum (Pittosporum undulatum) and spikerush (Lomandra longifolia).

The vegetation would originally have consisted of shrubby woodland dominated by smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata), with fewer Sydney peppermint (Eucalyptus piperita) and red bloodwood (E. gummifera), and subdominant small trees Christmas bush (Ceratopetalum gummiferum), black sheoak (Allocasuarina littoralis) and various sclerophyll shrubs on the ridges, slopes and headlands. This would have passed into a depauperate rainforest in the sheltered gullies running down to the harbour, these dominated by Moreton Bay fig (Ficus macrophylla) and lillipilli (Acmena smithii) with subdominant cheesewood (Glochidion ferdinandi), black pencil cedar (Polyscias elegans), sweet pittosporum (Pittosporum undulatum) and bleeding heart (Omalanthus nutans). Swamp sheoak (Casuarina glauca), Port Jackson fig (Ficus rubiginosa) and coastal banksia (Banksia integrifolia) are still to be found dominating the rocky shoreline vegetation with subordinate tough herbs such as matrush (Lomandra longifolia) and blue lily (Dianella caerulea) beneath.

Eight species occur on the site that can be considered native there. These are Angophora costata, Banksia integrifolia, Dianella caerulea vel aff., Elaeocarpus reticulatus, Ficus macrophylla, Ficus rubiginosa, Lomandra longifolia and Pittosporum undulatum.

With the early site development and building of Kirribilli House came levelling and smoothing of landscape contours. Together with the early build and later house modifications, these site interventions are still partly discernible as benching and banking. Apart from the marine precinct, various archaeological resources—especially within the northeast lawn and the elevated area west of the house—may also reveal some of this early development.

Evidence of the nineteenth-century layout remains apparent in areas such as:

Also, of nineteenth-century origins are:

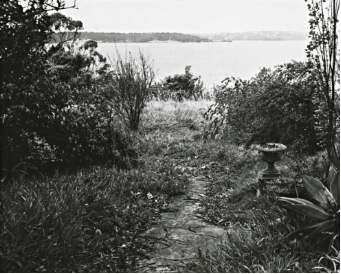

From archival material it appears the garden walk followed approximately the present path—winding down from the northeast verandah, past the northern fence, then generally along the contour across the grounds close to the eastern cliff line before, possibly, climbing again along the southern boundary.

The 1890s images from the Mitchell Library (refer to Figures B.5 and B.6 in Appendix B) also show various flights of steps within the reserve allowing access to the water. It is feasible that some, if not many, of the existing steps within the reserve were built as part of the Kirribilli House development in the nineteenth century and simply reused as convenient water access when the reserve boundaries were established (probably) in the early twentieth century.

Some of the extant plantings, such as the two bull bays (Magnolia grandiflora) behind the house and the large camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora) at Kirribilli Avenue, are very likely to have been introduced in the nineteenth century. Others are either also possibly from the nineteenth century or early twentieth century such as the large clumping plants Strelitzia nicolai (near the southern boundary and northern boundary) and Phoenix reclinata (near the path to the marine precinct), and the solitary Firewheel Tree (Stenocarpus sinuatus) at the northern boundary fence.

Other likely nineteenth-century plantings that have since been removed include the lemon-scented gum (Corymbia citriodora) at Kirribilli Avenue, the flame tree (Brachychiton acerifolium) formerly within the front drive loop, another camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora) formerly near the northern boundary, and the kauri pine (Agathis robusta) formerly near the northeast corner of the house.

Beyond individual plant species, a hallmark of the historical grounds evident in the archival photography is the rich character of the gardens created through use of a variety of foliage plants and strategic placement to provide shade, shelter and screening. There are only glimpses of such compositional richness and structural organisation within the present grounds, and these mostly occur where older trees remain as a foundation for later plantings.

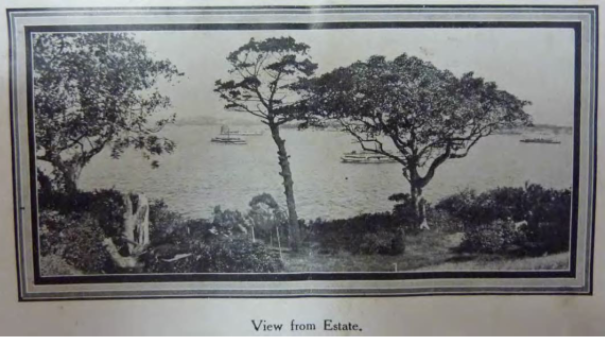

The prospect of spectacular harbour scenery, from both house and grounds, has been a feature of the place since the 1850s—though the site undoubtedly also offering scenic prospects for countless others a long time before that. Historically, as is the case presently present, the grounds offered vistas (eg from the front entry), filtered views and glimpses of the harbour through foliage, and broad panoramas.

There are also other important legacies from the nineteenth century still manifest at Kirribilli House. These include the enduring relationship the place has with its immediate neighbour, Admiralty House, from which estate the Kirribilli House grounds were originally subdivided. It is both rare and remarkable that these two major marine estates remain essentially intact. The two are appreciated together from around the harbour and are regarded as integral parts of the iconic harbourside scenery.

There is also considerable collective value contributed by Kirribilli House, Admiralty House and many of their surviving nineteenth-century neighbours such as Sunnyside (1862), Burnleigh (c1875), Newton (1870) and the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre building (1873). There is also value in the contribution Kirribilli House makes in combination with its streetscape neighbours, such as the residence across the road.

After changing ownership several times from 1913, Kirribilli House was acquired by the Commonwealth of Australia in 1920. Several changes within the grounds are discernible from the earlier part of this period.

An obvious one is that the present garage (built by 1930) now stands as a replacement for the former outbuildings to the west of the house. Between 1920 and 1930 the property was tenanted to various prominent people and it is possible that the present Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) and the nearby jelly palm (Butia capitata) were introduced, along with the Himalayan cedar (Cedrus deodara). It is possible other trees may date to this general period also—such as the Hill’s fig tree—though it is unclear if this was planted or bird-propagated. Alternatively, this tree was introduced as part of the 1957 grounds makeover.

The 1957 letter from L D Pryor records the existence of a lillipilli (possibly still remains), kauri pine (removed), the flame tree (removed), lemon-scented gum (removed) and Ginkgo biloba (removed). Many of these trees would have been planted prior to 1920, though it is possible the lillipilli was one that was introduced after 1920.

Correspondence from 1922 indicates that Charles Weston, as head of the Yarralumla Nursery in Canberra, was directly involved in the despatch (and possibly also the plant selection) of species to Kirribilli at that time. Weston would have known the site, its soils and microclimate intimately as he was formerly the head gardener at Admiralty House for 10 years, living on site in the gardener’s cottage before moving across the harbour to work at Government House for a further four years.

Much of the current layout in the northern and western sides of the grounds dates to the major transformations of the 1957 construction phase. During this period, the staff wing and other building alterations were undertaken. The driveway and drive loop were also added. Even the eastern side was affected banking was continued across the site with the addition of more flights of steps, and the earlier more dramatic bank was terraced to help use up spoil from the excavation on the western side.

A further flight of steps (and extended garden bedding) appears to have been added in the 1970s (possibly during the Fraser incumbency) to the southern end of the central rock formation. The repeated practice of adding flights of steps at various places with no connecting pathway created more problems than it solved. Each new set of steps then required a later pathway only to be confronted with the necessity of more steps to negotiate remaining changes of level. An unfortunate consequence of this cycle was the gradual erosion of the earlier sense of ‘wildness’ and drama that befitted the picturesque character of the site.

The 1957 report on the work at Kirribilli House states that Professor EG Waterhouse assisted with advice on the grounds in 1957. While having a distinguished academic career as a linguist, Waterhouse was also well respected as a horticulturist and camellia expert even to the point of becoming an advisor on landscape projects at Sydney University (main quadrangle, vice- chancellor’s courtyard and St Paul’s College campus), the Teachers’ College and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. It is assumed that the older camellias within the grounds, including those below the central rock outcrop and the large Camellia reticulata at the southern boundary, would have come at the suggestion of Waterhouse.

The large Hill’s fig tree is more problematic. It could either have been introduced sometime between the interwar period to 1950s or been propagated by birds during this time span. The very broad, spreading canopy of the fig tree is affecting the viability of plants under it, including a large group of locally indigenous species such as Angophora costata. Other smooth-barked apples lined the main driveway in the 1960s and 1970s, but had gone by 1986. The smooth-barked apple is a species that is otherwise highly desirable to have on site.

The mature Macadamia and Backhousia seem about the same age and were plausibly planted c1960sthere is no sign of the Macadamia in the 1957 photography of the western area and driveway precinct. It is possible that these plantings were instigated by Bettina Gorton (resident 1968 to 1971) as it is consistent date-wise and circumstantially—especially given her demonstrated advocacy of Australian flora and in providing the impetus for the famous Native Garden at The Lodge.

While possibly an earlier introduction, the aggressive Ficus pumila that functions as a makeshift hedge along the central rock outcrop may have been introduced as part of the 1980s recommendations. However, it is now threatening to engulf everything around it including rock outcropping and any other nearby plants—even trees. Although seemingly demure in its small-leafed juvenile stage it soon develops a larger and more aggressive adult type of foliage, and Sydney’s climate is very conducive to its fast-spreading and invasive habit. It probably should not be retained on site.

Very recent additions to the grounds include kentia palms (Howea forsteriana) (an appropriate choice in cultivating a Victorian landscape character) at the northern side of the house and, during the Rudd incumbency, a jacaranda within the drive loop as a replacement for the lost flame tree.

Of particular concern is the obvious demise of several older trees, such as the large camphor laurel, old flame tree and large lemon-scented gum, along with the near total defoliation of the remaining large camphor laurel. A solid and continuous line of trees along the northern boundary appears to have been a key feature of the place since at least the early twentieth century and likely earlier.

The 1950s remodelling of the northern spaces was a radical departure from the nineteenth and early twentieth century form, but was ameliorated by the retention of the mature trees along the northern boundary and along the driveway. The loss of many of these trees has had a substantial impact. Currently the important arrival spaces (whole northern side) are a partly successful development from the bland and austere landscape apparent in the 1980s. There is also currently evident a preponderance for neatness rather than a rich mixture of plant species consistent with a Victorian harbourside mansion.

There appears to be no clear direction on either the treatment of major precincts within the grounds such as the important approach sequence or the eastern cliff line where earlier exotics and locally indigenous vegetation are vying with environmental weeds—or the use of lighting elements and furniture (eg the inappropriate kidney-shaped stone seat). Walling varies from 1960s ‘fieldstone’ walls to very poor-quality mortared stone walling that needs replacing.

The former marine entry and saltwater pool precinct remains ruinous after the 1960s removal or unnecessary displacement of much stonework.

The purpose of this review of documentary material is to determine, as much as possible, what the place was like in its earlier phases and then, by comparing these characteristics with current evidence, establish a basic site development chronology and level of integrity that then helps to inform the assessment of significance. To do this each of the key archival records are analysed below and obvious site developments are noted.

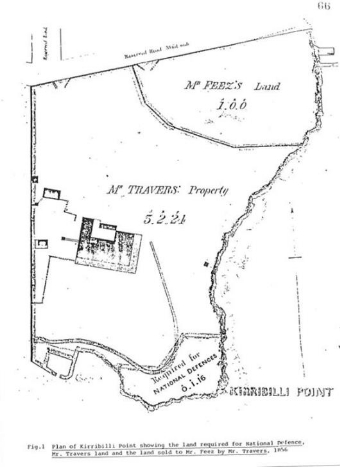

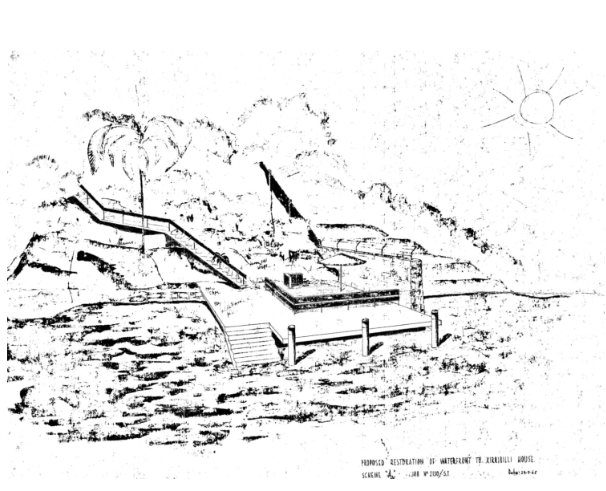

A plan of 1856 shows the land acquired by Mr Feez from Mr Travers as well as land required for national defence purposes at the southerly point (Kirribilli Point[100]) (Figure 1‑9).

Figure 1‑9: 1856 plan showing area required for national defence purposes

The plan clearly shows the arcing boundary with Wotonga (sic) as it was separated by subdivision. It also shows the splayed entry recess from the road reservation at the north-western corner of the site along with boat mooring structures into the harbour at the eastern edge. The road reservation also shows some indecision with a bold line denoting the northern boundary of the Kirribilli site but a dotted line projecting further to the north.

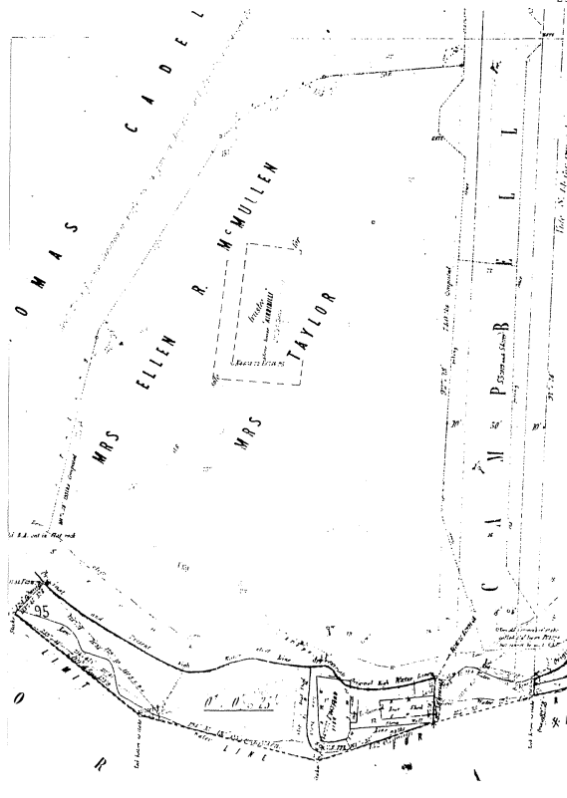

The 1883 plan for the Parish of Willoughby indicates the presence of the house ‘Kirribilli’ shown dashed graphically, the splayed entry recess of Campbell Street and the confusing eastern end of the northern road reserve where the northern property boundary seems to twist out to the north-east over the road reserve.

Of particular note is the extent of substantial development of the marine facilities where two enclosures are shown – one labelled ‘Boat Shed’ (to the north and parallel to the harbour) and the other “Fish Pond”[101] (to the south and perpendicular to the harbour). Above these is a line indicating the upper extent of the cliffs near the eastern boundary of the site and the faint indication of the access linking the maritime facilities with the top of the cliffs which accords with the present line of access between the two.

This document records the detailed field notes of the site by Surveyor T G Wilson and, although not drawn to scale, provides descriptions of structures and materials. One of the areas of interest is at the harbour edge where the marine facilities are outlined and described as containing at least three weatherboard boathouses and three flights of, presumably, stone steps. Some form of safety balustrading is also shown graphically at each of the water edges.

Another area of interest is at the north-eastern corner of the house where splayed steps are shown off the northern end of the verandah and, further to the east, a rectangular outline is described as being weatherboard with (as far as can be deciphered) the word, “Tank” in it.

Beyond this, the northern boundary is noted as being fenced, the splayed entry recess is clearly outlined, some bedding is shown in front of, and parallel to, the northern house bay outline, substantial weatherboard buildings are shown to the west of the house with a cobblestone area between them and a verandahed link to the house. A note to the left of the field sketch indicates that the spire of St Mark’s (presumably Darling Point) was used to make directional references.

This plan is probably the finished version of the previous in sketch form and is virtually identical to another survey of 5 April 1892 in the Stanton Library and the 1985 CMP report. The plan confirms the status of buildings and other structures across the site by this time including the full complement of built elements at the marine entry, the western outbuildings to the house and the small weatherboard structure to the northeast of the house labelled as “Tank”.

It also confirms the general alignment of the eastern cliff line, adjoining outbuildings with Admiralty House and provides yet another permutation to the northern boundary line in relation to the road reserve (still Campbell Street).

While offering no new information about site development this plan does continue to confirm that the site allotment has remained exactly the same since its subdivision in the 1850s.

Evidence of the direct involvement of Charles Weston and the Yarralumla Nursery in the review of Kirrabilli House grounds after its government acquisition is provided in a letter from the Afforestation Branch in Canberra of 12 May 1922. The following plants (the old nomenclature is retained) were despatched by Weston from Queanbeyan Railway Station to Mr M Minnett, Head Gardener, Admiralty House via Milsons Point Station:

The large number of Cupressus macrocarpa suggests their use for a hedge but no such feature currently remains part from a solitary cypress to the east. Of the other species listed here, only one Deodar Cedar remains and the preponderance of conifers is quite consistent with Victorian taste.

Although somewhat sparse in detail, this extract off the 1930 plan for the Parish of Willoughby shows the present motor garage. This indicates that it was probably built in the 1920s following the purchase of Kirribilli House by the Commonwealth of Australia. The plan also shows the house footprint through no outbuildings.[102]

An indicative rendering of the main gate entry is shown as a curved bay indent. The most elementary indication of buildings is shown adjoining the site boundary with Admiralty House though no structure is shown in the lawn to the northeast of Kirribilli House. This may mean that the former weatherboard structure with the ‘Tank’ has also been removed by 1930.

A watercolour rendering by G V F Mann in 1932 shows Kirribilli House in a dramatic setting from the southeast. The house is framed by vegetation on the extreme left (existing Bull Bay [Magnolia grandiflora]?) and to the right (a former Moreton Bay Fig Tree [Ficus macrophylla]) with a dense, continuous line of vegetation behind the house to the northeast.

Of note also is the sheer, even grassed bank falling to the harbour from the verandahs indicating the earlier (typical 19th century) form of the banking before the present terraced arrangement. The 1985 report also describes the colours used in the work anticipating black and white copies of the document.

This very useful record of the marine entry precinct details levels, layout and materials used throughout this important area. Of note are the annotations for the stepped access to the area from the main grounds. The extended, straight section – in exactly the same alignment as that existing – was built from two long flights of timber steps off concrete steps at the top with a long flat section using natural rock outcropping.

Although the earlier surveys of this area do not reveal the connection between the shoreline and the upper grounds, it is likely that this line of access has remained constant, only the materials being changed.

Other survey notes describe where bedrock has been cut to form steps or the boat harbours; masonry blocks used to form the arcing breakwater; and concrete steps added to provide better access. However, no buildings are indicated.

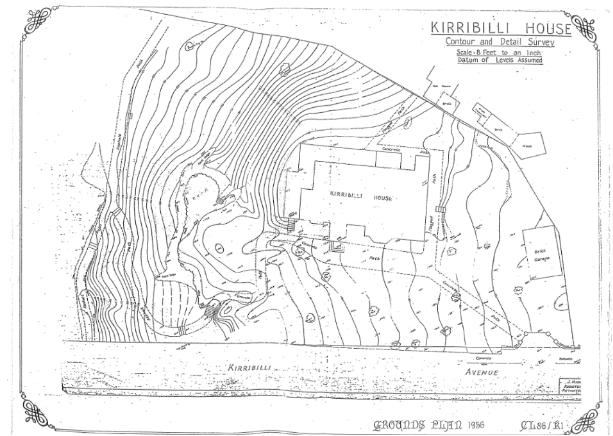

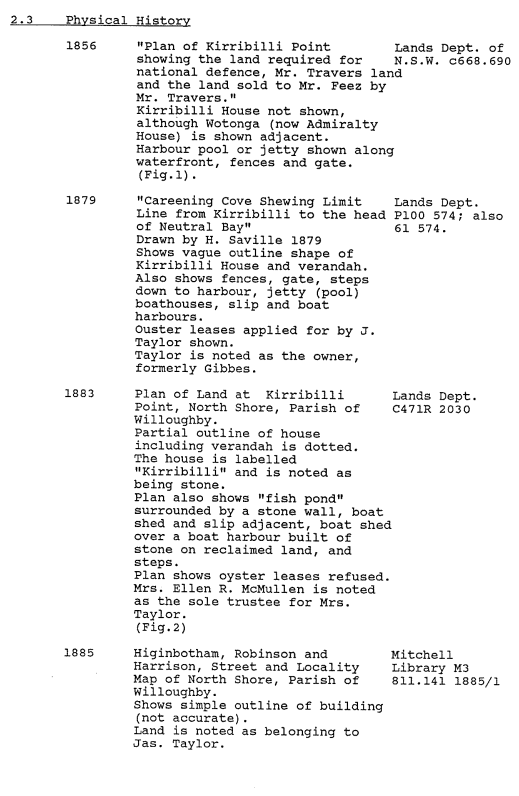

This important survey plan forms one of the most crucial records of the grounds as it describes the character, layout, levels and some of the features of the site just before the most transformative phase since the initial site development about one hundred years earlier. A reading of this survey with the 1957 grounds plan provides much information about the extent and scale of 1950s interventions.

The 1956 survey clearly shows the uniform steep bank (Figure 1‑10)[103] off the house verandahs before the present terraces were introduced, the earlier main entry gate ensemble at Kirribilli Avenue (including placement of piers – most matching the existing arrangement), the earlier flights of steps off the northeast verandah and main entry porch and the arrangement of the entry path (shown in concrete by this date).

A flagged path is described running along the western end of the house, then a concrete path at the southern return but with another stone flagged section (and associated ornamental pond) linking the house with the boundary to Admiralty House. A flight of steps is shown adjacent to the western doorway leading up a bank.

The concrete path at the front house entry continues in a series of (presumably ramping) bends to steps down the steep slopes to the northeast of the house finally leading to an asphalt path that traverses the upper edge of the eastern cliff line. Unlike photographs of the same period, this plan also confirms the existence of a designated garden walk within the grounds as would be expected of most places of this scale.

In a line projected off the northern façade of the house there is a note of ‘steps’ beyond the eastern cliff line indicating the access to the marine precinct and further to the south is a rectangle possibly indicating the lancet-shaped lattice portal shown in archival photographs. Apart from the house and the garage, no other structures are noted.[104]

Figure 1‑10: 1956 Survey Plan (Department of Housing and Construction Landscape Architects ACT Region, 1986)

Also east of the house verandah is the present large rock outcrop formation along the central part of the eastern grounds. The survey records the upper cliff edge as well as the lower rock ledge. The form of the outcropping appears to have dictated the location of steps with one flight shown to the north skirting above the rock while, to the south, a flight (presumably the existing one cut into the rock) is shown wedged between rock outcrops.

Not all of the annotations for existing vegetation are decipherable or provide identification, especially on the northern side of the house. Those that are, however, include a ‘Moreton Bay Fig’ in the southeast of the grounds, a ‘Magnolia’ at the bottom of the bank near the Admiralty House boundary and, what appears to be, a ‘Grey Gum’ to the north of the house. Given the general level of identification evident the latter may have been a locally indigenous Angophora costata. All other plant symbols appear to be labelled, “Tree”. Correlation with later records, however, soon reveals the identity of many of these otherwise anonymous former and existing species.

Two of the 1956 drawings used for the later site contract work document the extent of changes to the Kirribilli House landscape since the 1956 survey. Drawing 56 1411/1 provides ground and first floor plans and an elevation and section where substantial cut and fill is indicated, and instructions given such as ‘remove stone steps’ for the former splayed steps to the northeast verandah as well as those to the front porch.

The elevation and section reveal that the former outbuildings (removed by 1930) must have been built across the rising ground to the wet of the house with stabling closest to the western boundary. As it shows the line of the earlier ground levels west of the house it implies that a considerable amount of cut material has been excavated to allow for the 1957 staff wing and that, where levels have been retained or filled (such as above the stone retaining walls), there may remain some archaeological evidence of the former 19th century outbuildings.

At the northeastern side of the house the elevation and ground plan show where levels have been filled to raise the new drive loop to meet the upper slab of the entry threshold. This was done on the basis of attempting to retain the two existing trees in this location – the one in the front of the porch being a Flame Tree and the other possibly a Kauri Pine (both trees have since gone).

The ground plan also shows an earlier version of the path layout to the northeast of the house and confirms the intention to reconfigure the levels around this area consistent with the raised driveway. It is possible – and logical – that excavated material from the staff wing was used to fill areas for the drive loop and the bank terracing to minimise the contract cost of removing soil off the site.

Another drawing (56 1411/4) confirms the arrangement of the gated entry in 1956 and the extent of modification required by the new work. This entailed retaining the two sandstone walls and enclosing piers facing Kirribilli Avenue along with the western pier forming a gate top the west. The earlier pedestrian gate and inward pier were removed with a new curving section of stone wall being built to enclose new wrought iron gates.

The drawing also shows that an existing timber paling fence was retained along part of the northern boundary, though this has since been replaced.

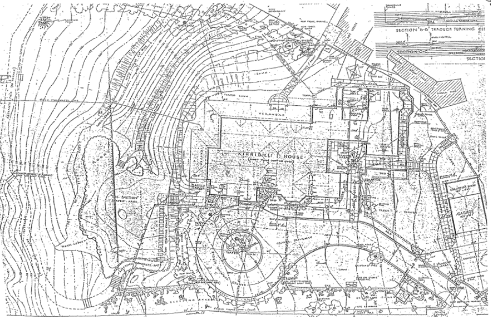

Together with the 1956 site survey, this plan readily reveals the extent of changes arising from the 1957 works contract among which include the broadening of the old earth bank to the east and formation of two intermediate terraces; the filling of the area in front (north) of the house and introduction of a paved (gravel) drive loop and turning circle, the removal of earlier stone steps (and early iron railings); the reconfiguration of the entry gates and the addition of the staff wing along with associated stone retaining walls and steps following substantial excavation.

With substantial interventions to the west, north and southeast of the house the 1957 work effectively changed about half of the grounds. The nature of some of these changes – such as the introduction of the bank terraces – also meant that further changes were left implied, and which were duly fulfilled subsequently. In the case of the terraces later changes included the addition of more steps and paths to take advantage of the easier access provided by the terracing.

Other site modifications involved replacing the earlier southern connection to Admiralty House with a new flagged pathway (and a new paling fence and gates) and curved threshold where the earlier conservatory was demolished, the provision of a new stone paved connection into the grounds of Admiralty House from the new western courtyard. Interestingly the former small pond next to the southern pathway has gone.

Curiously, however, while one of the old bull Bays are shown near the southern boundary and the former Moreton Bay Fig Tree is not shown (as it has presumably been removed), the plan shows the present mature Jelly Palm as an ‘existing palm’ – along with a small pond next to it – though the 956 survey omitted the palm even though it must have been present.

In a letter to the Prime Minister’s Department the architects Fowell, Mansfield and Maclurcan set out their design intentions for the grounds of Kirribilli House, foremost of which were the objectives of ‘economy of maintenance’ and ‘to present the appearance of a garden to a private house than that of an official building’. A preliminary plan originally accompanied the letter, but this has not been found.

The recommendations further listed that the immediate house environment be cultivated with plants ‘suitable to the architecture’ and ‘favoured by the early pioneers’. Two remaining objectives are particularly interesting as they advocate the use of Australian plants generally for the benefit of overseas visitors and the use of locally indigenous species along the harbour edges.

A later suggestion in this letter, referring to the intermediate outcrop known as “The Bastion”, is for the existing ‘ficus and other growth along the cliff edge’ to be ‘severely cut back and to some extent removed’ and, where feasible, replaced using ‘more interesting native plants’. This may refer to the existing problematic Ficus pumila that has covered the entire rock outcrop and many of the plants around it.

The letter also includes many plant species suggestions and locations for these and, despite emphasising the need to reduce maintenance commitments, specifies the use of annuals, herbaceous borders, hedges and fruit trees. Camellias and azaleas were stipulated as feature plants within the northern entry areas and even climbing plants ‘of restrained habit’ were suggested for corner verandah posts.

The demise of the old fig tree at the south-eastern corner was contemplated in 1957 as the letter indicates that it ‘will probably be removed and a plantation of Callitris is suggested at this point’. The existing examples of Monstera deliciosa probably date from the later 1950s as this species is recommended in the letter as well as Acanthus.

Two letters from Professor Lindsay Pryor, then Head of the Parks and Gardens Section of the Department of the Interior, to Ken Herde of the Prime Minister’s Department provide considerable insight into the thinking behind the changes to the grounds at Kirribilli House in 1957. In the first of these letters, Pryor acknowledges the existence, and desirable retention, of a number of the earlier plantings such as a Kauri pine and the Flame Tree near the main entry of the house, a Lillipilli (possibly the existing Syzgium to the lower north-east grounds) and a Lemon-scented Gum (probably the one now cut down at the northern boundary).

Pryor also graciously offers advice on Mr Mansfield’s landscape planning and makes various recommendations to fine-tune the Fowell, Mansfield and Maclurcan proposals. Chief among these considerations is the need to reduce areas of lawn where the amount of shade would preclude its viability. However, the shade regime current when Pryor was writing was quite different to that of today on account of the recent loss of so many of the larger canopy trees.

In supporting Mansfield’s proposal for native plants around “The Bastion” area, Pryor provides a list of suitable species that include some local Sydney plants such as Eriostemon (now Philotheca), Banksia spinulosa, Telopea and Grevillea buxifolia. Pryor goes on to suggest the addition of several NSW rainforest trees such as Red Ash (Alphitonia excelsa), Red Cedar (Toona cedrela) and Flindersia oxleyana (syn. F. xanthoxyla) for the lower grounds.

Other exotic trees recommended by Pryor, such as Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) ‘to accompany the fine Ginkgo which already exists’ along with a Chinese Elm (Ulmus chinensis), Swamp Cypress (Taxodium distichum) and Zelkova. Concluding paragraphs indicate that camellias and azaleas are likely to be ‘extremely expensive’, though certain strategic locations may justify such expense and that an umbrageous tree is warranted near the main entry gates – a role presently filled by the large Macademia tetraphylla though apparently not included in the 1957 plantings.