Kirribilli House and Garden Heritage Management Plan 2025–2030

I, Steven Kennedy, Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, acting pursuant to subsection 341S(2) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, make the Kirribilli House and Garden Heritage Management Plan 2025–2030, to protect and manage the Commonwealth Heritage values of the Commonwealth Heritage places, Kirribilli House and Kirribilli House Garden and Grounds.

This instrument commences on the day after it is registered.

Dated this day of 15 August 2025

Dr Steven Kennedy PSM

Secretary

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Prepared for

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

ABN: 18 108 001 191 2

Heritage Management Plan – Volume 1

Kirribilli House and Garden, Kirribilli, NSW

05-Feb-2025

Kirribilli House HMP Update

Doc No. FINAL

Heritage Management Plan - Volume 1

Kirribilli House and Garden, Kirribilli, NSW

Client: The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

ABN: 18 108 001 191 2

Prepared by

AECOM Australia Pty Ltd

Gadigal Country, Level 21, 420 George Street, Sydney NSW 2000, PO Box Q410, QVB Post Office NSW 1230, Australia

T +61 2 8008 1700 www.aecom.com

ABN 20 093 846 925

05-Feb-2025

AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to ISO9001, ISO14001 and ISO45001.

Quality Information

Revision History

Rev | Revision Date | Details | Approved |

Name/Position | Signature |

A | 20-Jun-2023 | Draft | Dr Darran Jordan, Principal Archaeologist and ANZ Technical Lead |

|

B | 18-Oct-2023 | First draft comments addressed | Dr Darran Jordan, Principal Archaeologist and ANZ Technical Lead |

|

C | 27-March-2024 | Final comments addressed | Dr Darran Jordan, Principal Archaeologist and ANZ Technical Lead |

|

D | 07-May-2024 | Final comments addressed | Dr Darran Jordan, Principal Archaeologist and ANZ Technical Lead |

|

E | 05-Feb-2025 | Additional comments addressed | Dr Darran Jordan, Principal Archaeologist and ANZ Technical Lead |

|

Professional Registration

This document includes professional services that require approval from a registered professional.

Registration Scheme | Discipline /

Area of Practice | Name of Registered Professional* | Signature | Registration No. | Date |

NSW Board of Architects | Heritage | Ameera Mahmood |

| 8254 | 21/06/2023 |

* The registered professional must be the originator of this work or have provided direct supervision to the originator.

Table of Contents

Heritage Management Plan - Volume 1 2

Quality Information 3

Executive Summary i

1.0 Introduction 3

1.1 Background 3

1.2 Site location 3

1.3 Heritage status 3

1.4 Previous key heritage reports 7

1.5 Objectives 7

1.6 Stakeholder roles and responsibilities 9

1.6.1 Management of Kirribilli House 10

1.7 Methodology 10

1.7.1 General 10

1.7.2 Assessment of significance Thresholds 11

1.7.3 Significance Assessment under the EPBC Act 11

1.7.4 Knowledge Gap Analysis 15

1.8 Consultation 16

1.8.1 Public exhibition 17

1.9 Assumptions and Limitations 17

1.10 Authorship 17

1.11 Acknowledgements 18

2.0 Statutory Controls 19

2.1 Commonwealth Controls 19

2.1.1 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 19

2.1.2 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 20

2.2 State and local legislation 21

2.2.1 Heritage Act 1977 (NSW) 21

2.2.2 Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) 21

2.2.3 North Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2013 (Local) 22

2.2.4 North Sydney Development Control Plan (DCP) 2013 23

2.3 Other relevant Legislation and Codes 23

2.3.1 National Construction Code (NCC) 23

2.3.2 Disability Discrimination Act 1992 23

2.4 Non-Statutory Information and Guidelines 24

2.4.1 The Burra Charter 24

2.4.2 Ask First: A Guide to Respecting Indigenous Heritage Places and Values 24

2.4.3 Engage Early 24

2.4.4 Australian Natural Heritage Charter 24

2.4.5 National Trust of Australia 25

3.0 Site background 26

3.1 Introduction 26

3.2 Landscape setting 26

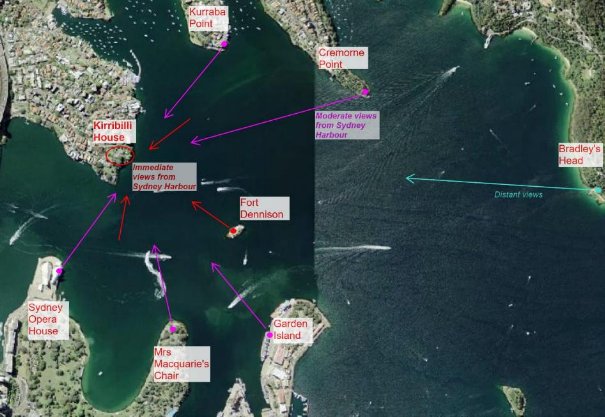

3.2.1 Broader views and vistas to Kirribilli House 28

3.2.2 Description of the allotment 29

3.3 Kirribilli House 31

3.3.1 Exterior 31

3.3.2 Internal Description 33

3.3.3 Condition 37

3.4 Garden 38

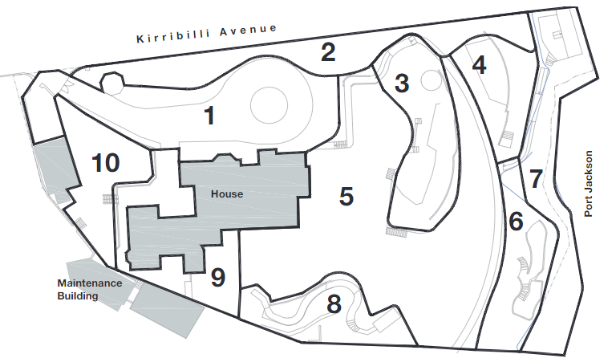

3.4.1 Garden areas 39

3.4.2 Area 1 – Entry gate and driveway 39

3.4.3 Area 2 – Northern boundary garden 40

3.4.4 Area 3 – Central Garden 40

3.4.5 Area 4 – Viewing Area 41

3.4.6 Area 5 – Lawn 42

3.4.7 Area 6 – Upper foreshore 42

3.4.8 Area 7 – Foreshore 43

3.4.9 Area 8 – Southern Garden 44

3.4.10 Area 9 – Service Area 44

3.4.11 Area 10 – Kitchen Garden 45

3.4.12 Condition 45

3.5 Other elements 46

3.5.1 Guard house 46

3.5.2 Garage 46

3.5.3 Storeroom 47

3.5.4 Ruins of the boat harbour, bathing pool and boathouse 47

3.5.5 Boundary walls and fences 48

3.6 Views from Kirribilli House 48

4.0 Historical background 51

4.1 Indigenous History 51

4.2 Natural History 51

4.3 Historic heritage 51

4.3.1 Historical summary of the house 52

4.3.2 Historical summary of the garden 53

4.3.3 Timeline of events 55

4.3.4 Key Historical photographs 59

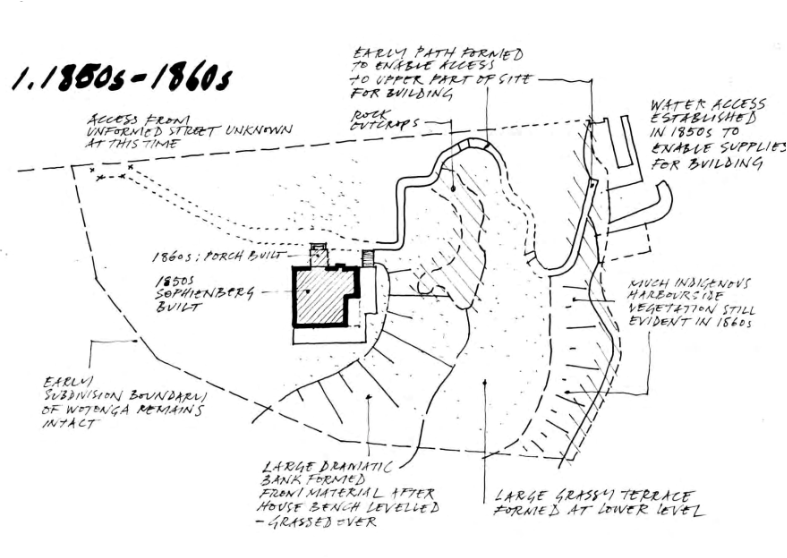

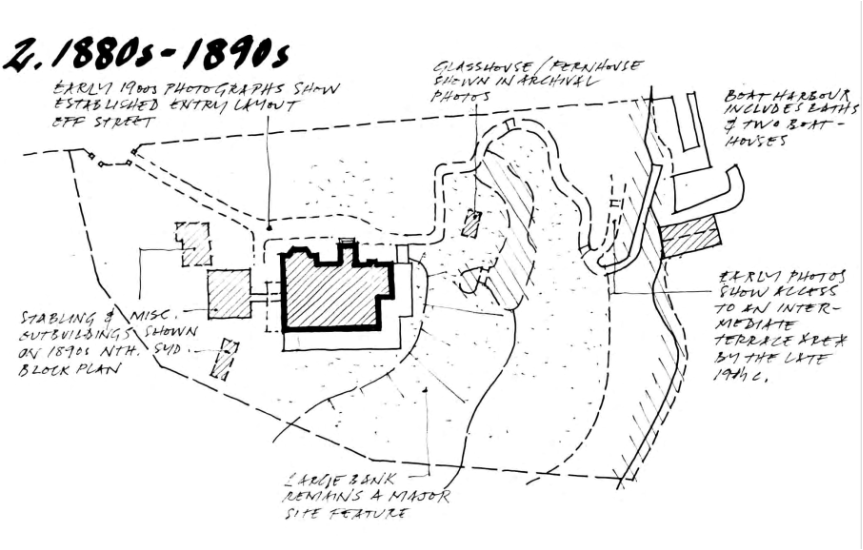

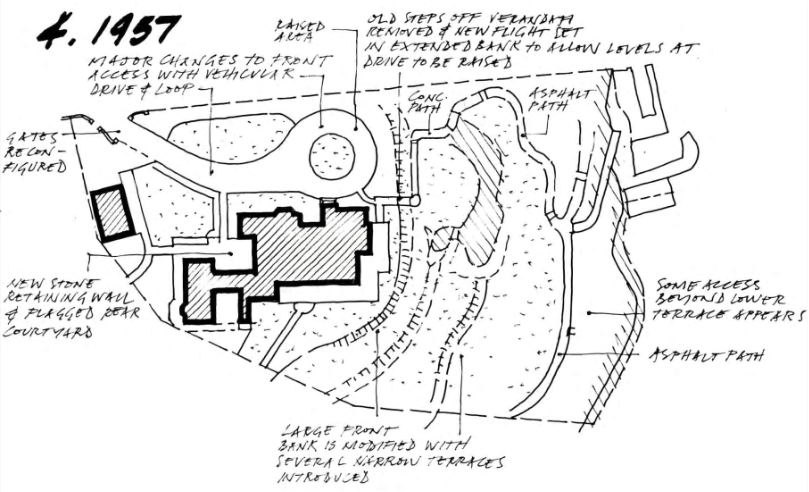

4.3.5 Kirribilli House Evolution Plans 62

4.4 Archaeological potential 71

4.4.1 Management of Unexpected Finds 74

4.4.2 Summary of Archaeological Potential 76

5.0 Significance assessment 77

5.1 Natural Heritage Assessment 77

5.1.1 Discussion 77

5.2 Indigenous Heritage Assessment 77

5.3 Heritage Context 77

5.3.1 Preamble 77

5.3.2 Kirribilli House 77

5.3.3 Kirribilli House Garden & Grounds 80

5.4 Condition and Integrity of CHL Values 83

5.4.1 Significance grading 85

5.4.2 Tolerance for change 86

5.4.3 Contributory elements and significance grading 86

5.4.4 Significance grading of landscape elements 111

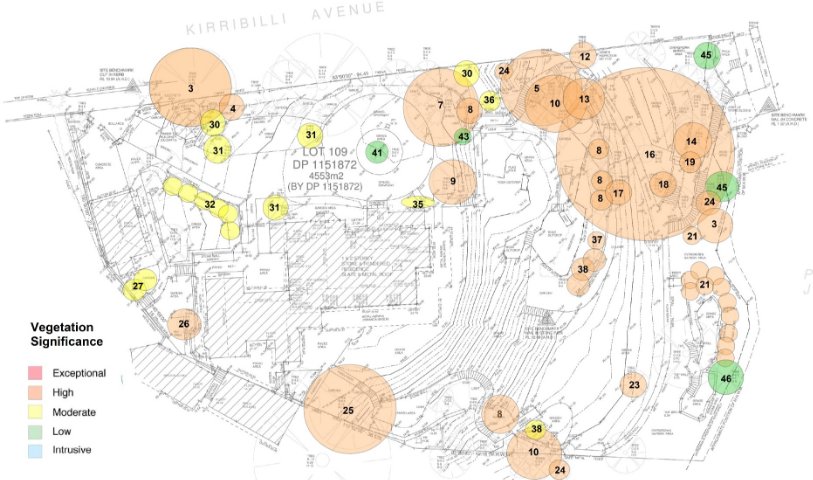

5.4.5 Significance grading of vegetation 111

5.4.6 Significance grading diagrams 112

6.0 Heritage Risk Assessment 117

6.1 Objectives 117

6.2 Description 117

6.2.1 Risk Assessment Methodology 117

7.0 Managing heritage values 124

7.1 Objectives 124

7.2 Opportunities and constraints 124

7.3 Planned Works 124

7.4 Policies and guidelines 125

7.5 Management Policies 125

7.5.1 Implementation and review of HMP 125

7.5.2 Change in Ownership or Lease 125

7.5.3 Expert advice, skilled trades 126

7.5.4 Training and resources 126

7.5.5 Roles and responsibilities 127

7.5.6 Internal works approval and record keeping 127

7.5.7 Legislative approvals process 127

7.5.8 National Construction Code (NCC) and Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) compliance 128

7.5.9 Safety 128

7.5.10 Access for people with a Disability 128

7.5.11 Planning and coordination 129

7.5.12 Stakeholder consultation 129

7.6 Security 130

7.6.1 Security and privacy 130

7.6.2 Security Infrastructure 130

7.7 Site-wide policies 130

7.7.1 Conservation principles 130

7.7.2 Setting 132

7.7.3 Streetscape 132

7.7.4 Significant views 132

7.7.5 Heritage curtilage 134

7.7.6 Masterplans 134

7.7.7 Grounds generally 135

7.7.8 House generally 136

7.7.9 Maintenance and repair 136

7.7.10 Emergency Works 137

7.7.11 Climate change, sustainability, and resilience 137

7.7.12 Indigenous cultural management 139

7.7.13 Services 141

7.7.14 Archaeological monitoring 142

7.7.15 Carparking and circulation 142

7.7.16 Public access 142

7.7.17 Archival recording 142

7.7.18 Movable items 143

7.7.19 Heritage interpretation 143

7.7.20 Signage and external lighting 144

7.8 Contributory elements 144

7.9 New work 148

7.9.1 Adaptive re-use 148

7.9.2 New development, additions and infills 148

7.9.3 Changes to function of spaces 149

7.10 Conservation in accordance with significance 149

7.11 Conservation of Materials 150

7.11.1 Traditional materials 150

7.11.2 Reconstruction 150

7.11.3 Colour schemes and finishes 150

7.11.4 Previous inappropriate conservation methods 150

7.11.5 Heritage reporting on the review and implementation of the HMP 150

7.11.6 Knowledge gap analysis 152

7.12 Implementation plan 154

8.0 Maintenance Schedule 155

8.1 Introduction 155

8.2 Catch-up Maintenance 155

8.3 Cyclical Inspection and Maintenance Schedule 161

See Volume 2 – Appendix A to Appendix Q

List of Tables

Table 1‑1: Site Identification Details 3

Table 1‑2: Heritage status - Summary of search results of relevant heritage registers 4

Table 1‑3 EPBC Act Compliance Checklist 7

Table 1‑4: Stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities for Kirribilli House 9

Table 1‑5 EBPC Act heritage significance criteria 11

Table 1‑6: Summary of Significance Rankings for Built and Indigenous Heritage 13

Table 1‑7: Summary of Significance Rankings for Natural Heritage Values 15

Table 1‑8: Registered Aboriginal Organisations consulted 17

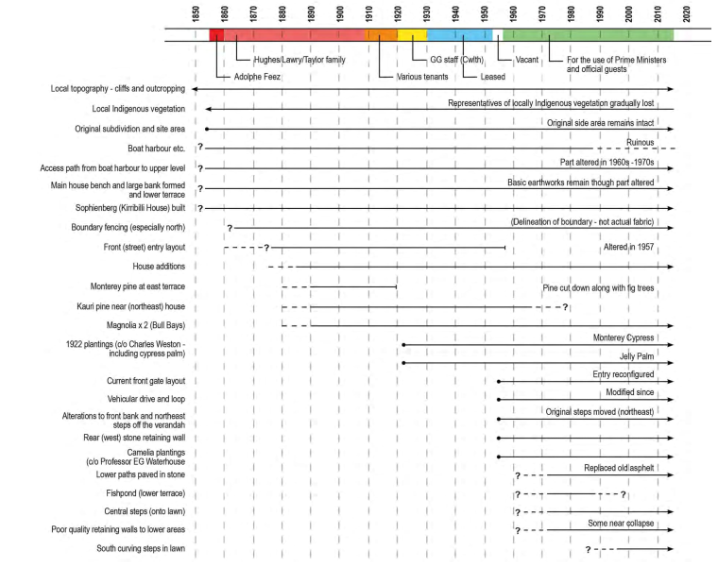

Table 4‑1: Site chronology 55

Table 5‑1: Condition Assessment of CHL Values Against Both Listings 84

Table 5‑2 Tolerance for change according to level of significance 86

Table 5‑3: Schedule of significant (contributory) elements 87

Table 5‑4: Significance grading of landscape elements (updated AECOM, 2023) 111

Table 5‑5: Significance grading of vegetation elements at Kirribilli House (location is shown in Figure 5‑57) (updated AECOM, 2023) 111

Table 6‑1 Likelihood rating matrix (assessment on the probability of the risk occurring) 117

Table 6‑2 Consequence Descriptions 117

Table 6‑3 Risk Management Framework Matrix 118

Table 6‑4: Risk Assessment 119

Table 8‑1 Catch-up maintenance 156

Table 8‑2 Cyclical Inspection and Maintenance Plan 162

List of Figures

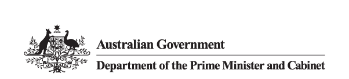

Figure 1‑1: Study Area 5

Figure 1‑2: Site Plan 6

Figure 2‑1: Sydney Opera House buffer zone extends to Kirribilli House (circled red) (SREP 2005) 21

Figure 2‑2: Extent of Kirribilli Heritage Conservation Area (CA11) in red hatching. Kirribilli House is circled in red (Source: NSW Government Planning Portal, North Sydney LEP 2013, Heritage Map 4) 22

Figure 3‑1: Kirribilli House (obscured by vegetation) and gardens showing context of the Sydney CBD, Opera House and extant bathing pool seen from the harbour ferry (AECOM, 2023) 26

Figure 3‑2: Adjacent Admiralty House, garden and Marine Barracks showing context of the Sydney Harbour Bridge seen from a harbour ferry (AECOM, 2023) 27

Figure 3‑3: Kirribilli House and garden seen from the harbour ferry (AECOM, 2023) 27

Figure 3‑4: Adjacent Admiralty House, garden, and Marine Barracks (below) and garden of Kirribilli House (right of photo) seen from a harbour ferry (AECOM, 2023) 27

Figure 3‑5: Broughton Street looking towards Kirribilli Village Centre (AECOM, 2023) 28

Figure 3‑6: Broughton Street lookout (AECOM, 2023) 28

Figure 3‑7: Residential buildings on Kirribilli Avenue (AECOM, 2023) 28

Figure 3‑8: Residential buildings on Kirribilli Avenue (AECOM, 2023) 28

Figure 3‑9: View from Sydney Opera House (AECOM, 2023) 29

Figure 3‑10: View from Cremorne Point (AECOM, 2023) 29

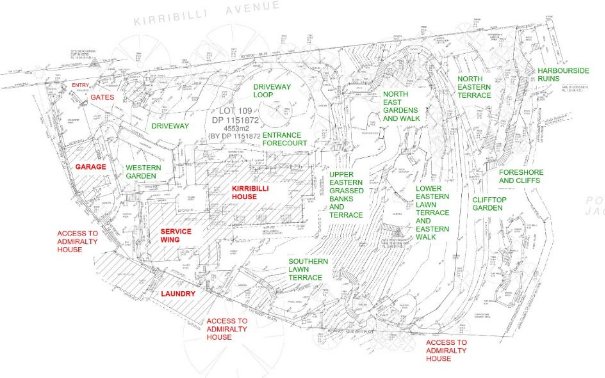

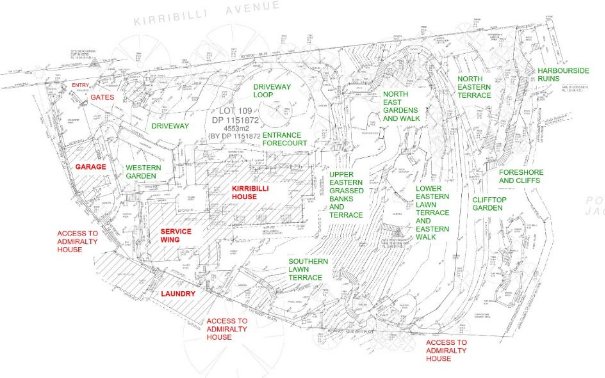

Figure 3‑11: Site survey and elements (GML 2016 with AECOM updates) 30

Figure 3‑12: Kirribilli Avenue looking west showing stone wall at property boundary and views to the Sydney Harbour Bridge (AECOM, 2023) 30

Figure 3‑13: Lady Gowrie lookout looking east showing timber paling fence at property boundary and views to the harbour (AECOM, 2023) 30

Figure 3‑14: Main entrance to Kirribilli House through iron gates from Kirribilli Avenue looking south (AECOM, 2023) 31

Figure 3‑15: Stone wall and transition to timber paling fence from Kirribilli Avenue looking south (AECOM, 2023) 31

Figure 3‑16: Kirribilli House from Kirribilli Avenue looking south (AECOM, 2023) 31

Figure 3‑17: North elevation (AECOM, 2023) 32

Figure 3‑18: East elevation (AECOM, 2023) 32

Figure 3‑19: Part south elevation (AECOM, 2023) 32

Figure 3‑20: Part south elevation (AECOM, 2023) 32

Figure 3‑21: West elevation (AECOM, 2023) 32

Figure 3‑22: Entry lobby detail 33

Figure 3‑23: Timber framed verandah detail (AECOM, 2023) 33

Figure 3‑24: Ground floor plan – Refer to Volume 3 33

Figure 3‑25: Entry lobby (AECOM, 2023) 33

Figure 3‑26: Stair Hall (AECOM, 2023) 33

Figure 3‑27: Stair Hall (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑28: Green room (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑29: Drawing room (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑30: Dining room (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑31: Second stairwell (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑32: Second stairwell (AECOM, 2023) 34

Figure 3‑33: Staff room (AECOM, 2023) 35

Figure 3‑34: Kitchen (AECOM, 2023) 35

Figure 3‑35: First floor plan – Refer to Volume 3 36

Figure 3‑36: Stairwell (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑37: Corridor (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑38: Family room (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑39: Bedroom 2 (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑40: Bedroom 4 (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑41: Bedroom 3 (AECOM, 2023) 36

Figure 3‑42: Early window hardware (AECOM, 2023) 37

Figure 3‑43: Early window hardware (AECOM, 2023) 37

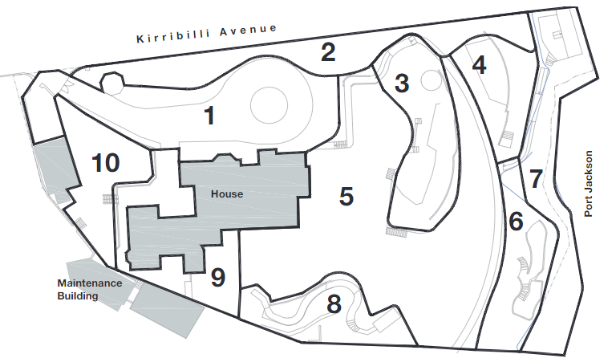

Figure 3‑44: Landscape areas within the grounds of Kirribilli House (Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects Pty Ltd, 2020:5) 39

Figure 3‑45: Entry gate and driveway (AECOM, 2023) 40

Figure 3‑46: Driveway loop showing Jacaranda (AECOM, 2023) 40

Figure 3‑47: Northern boundary (beyond) showing the loss of privacy from the erosion of canopy trees (AECOM, 2023) 40

Figure 3‑48:3‑49 Garden edges informally placed compromise the natural sandstone outcrop (AECOM, 2023) 40

Figure 3‑50: Sandstone outcrop (AECOM, 2023) 41

Figure 3‑51: Garden rock wall poorly constructed (AECOM, 2023) 41

Figure 3‑52: Flagged terrace and retaining wall (AECOM, 2023) 41

Figure 3‑53: Viewing terrace (AECOM, 2023) 41

Figure 3‑54: Steep slope of the lawn (AECOM, 2023) 42

Figure 3‑55: Poorly constructed garden walls (AECOM, 2023) 42

Figure 3‑56: Area bound by metal fence and shrub like plantings (AECOM, 2023) 43

Figure 3‑57: Shrubs and rock outcrops (AECOM, 2023) 43

Figure 3‑58: Concrete steps (AECOM, 2023) 43

Figure 3‑59: Mixture of random stone and brick retaining walls (AECOM, 2023) 43

Figure 3‑60: Plantings and paths defining the boundary to Admiralty House (AECOM, 2023) 44

Figure 3‑61: Paving and seating inconsistent with heritage values (AECOM, 2023) 44

Figure 3‑62: Existing gate and access (AECOM, 2023) 45

Figure 3‑63: Concrete paths inconsistent with heritage values (AECOM, 2023) 45

Figure 3‑64: Stone retaining wall and hedge to edge of area (AECOM, 2023) 45

Figure 3‑65: Kitchen Garden (AECOM, 2023) 45

Figure 3‑66: Guard house east elevation (AECOM, 2023) 46

Figure 3‑67: Guard house west elevation (AECOM, 2023) 46

Figure 3‑68: Garage north elevation (AECOM, 2023) 47

Figure 3‑69: Garage western elevation (AECOM, 2023) 47

Figure 3‑70: Storeroom west elevation (right of photo) (AECOM, 2023) 47

Figure 3‑71: Storeroom east elevation (centre of photo) (AECOM, 2023) 47

Figure 3‑72: Ruins of the boat harbour, bathing pool and boathouses (AECOM, 20223) 48

Figure 3‑73: Ruins of the boat harbour, bathing pool and boathouses (AECOM, 20223) 48

Figure 3‑74: Southern boundary to Admiralty House (AECOM, 20223) 48

Figure 3‑75: Western boundary (AECOM, 20223) 48

Figure 3‑76: Framed view of the Sydney Harbour from site entry (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑77: Panoramic views to Sydney Harbour, Fort Denison, and Garden Island from garden (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑78: Panoramic views to Sydney Harbour, Bradleys Head, Kurraba Point and Cremorne Point from garden (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑79: Panoramic views to Sydney Harbour and Sydney CBD from garden (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑80: Panoramic views to Opera House obscured by plantings, viewed from garden beds closest to foreshore (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑81: Filtered views to the Opera House from garden (AECOM 2023) 49

Figure 3‑82: Filtered views of Fort Denison from garden paths (AECOM, 2023) 50

Figure 3‑83: Panoramic views to Kurraba Point and Cremorne Point (AECOM, 2023) 50

Figure 3‑84: Framed view from upper-level window (AECOM 2023) 50

Figure 3‑85: Framed view from staff room (AECOM 2023) 50

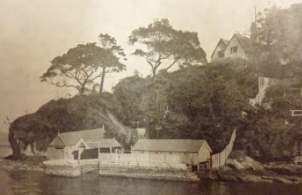

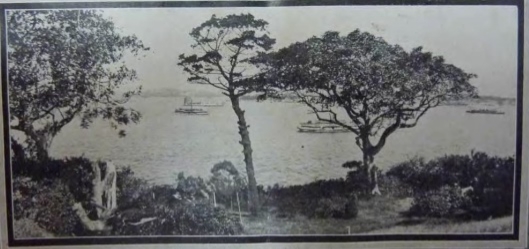

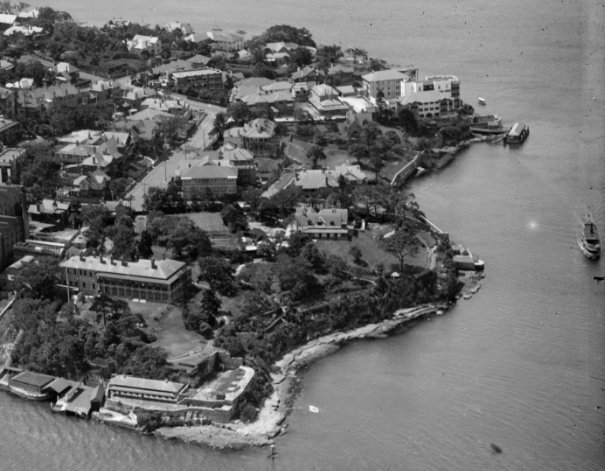

Figure 4‑1: 1890s SPF image showing Kirribilli House, thick vegetation in gardens and harbour structures (Source: Mitchell Library) 59

Figure 4‑2: 1890s SPF image showing detail of terraced gardens, manicured hedges, and harbour structures (Source: Mitchell Library) 59

Figure 4‑3: c.1920 Detail of Richardson & Wrench Sales Brochure, showing Kirribilli House and garden including plantings (Kirribilli House Subdivision: Richardson & Wrench Ltd –Saturday 17 January 1920 at 3.30 pm) 60

Figure 4‑4: Detail of Richardson & Wrench Sales Brochure, c. 1920 showing the bathing pool, stone walls, boat harbour and timber shelter and boatshed (Kirribilli House Subdivision: Richardson & Wrench Ltd – 17 January 1920 at 3.30 pm) 60

Figure 4‑5: c.1921, Detail of photograph of the Pastoral Finance Association Building (to the left of Admiralty House out of frame) on Kirribilli Point, taken by Milton Kent showing Kirribilli House, garden and harbourside structures (Source: State Library of NSW, ON 447/Box 123 60

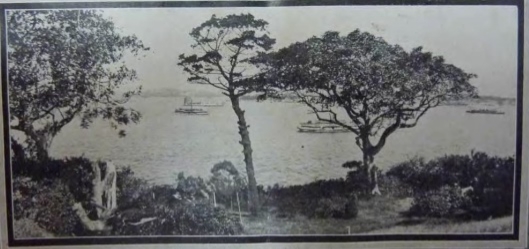

Figure 4‑6: 1920s View from the Estate Richardson & Wrench Sales Brochure showing panoramic views (Kirribilli House Subdivision: Richardson & Wrench Ltd –Saturday 17 January 1920 at 3.30 pm) 61

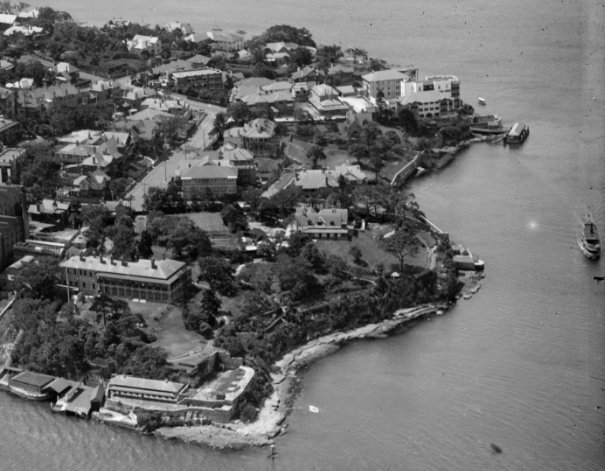

Figure 4‑7: 1943 Photographic aerial showing Kirribilli House prior to western extension (spatial.nsw.gov.au) 61

Figure 4‑8: 1965 Photographic aerial showing Kirribilli House after western extension (spatial.nsw.gov.au) 61

Figure 4‑9: 2005 Photographic aerial (spatial.nsw.gov.au) 61

Figure 4‑10: 2023 Photographic aerial showing loss of tree canopy to northern boundary (maps.six.nsw.gov.au) 61

Figure 4‑11: Ground floor plan evolution – Refer to Volume 3 62

Figure 4‑12: First floor plan evolution – Refer to Volume 3 62

Figure 4‑13: East and west elevations evolution (Source: Design 5 report 2010) 63

Figure 4‑14: North and south elevations evolution (Source: Design 5 report 2010) 64

Figure 4‑15: Kirribilli Grounds 1850s to 1860s (Source: Geoffrey Britton 2015) 65

Figure 4‑16: Kirribilli Grounds 1880s-1890s (Source: Geoffrey Britton, 2015) 66

Figure 4‑17: Kirribilli Grounds 1920s – 1930s (Source: Geoffrey Britton, 2015) 67

Figure 4‑18: Kirribilli Grounds 1957 (Source Geoffrey Britton, 2015) 68

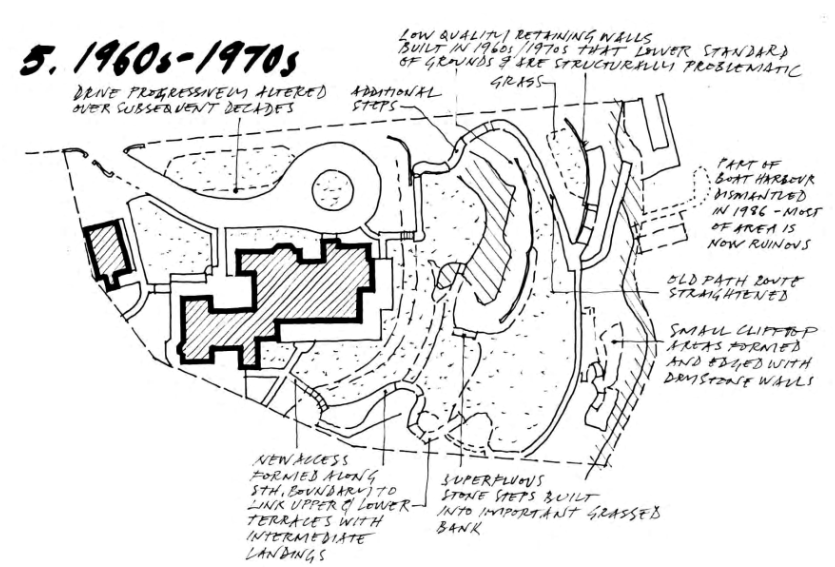

Figure 4‑19: Kirribilli Grounds, 1960s-1970s (Source: Geoffrey Britton, 2015) 69

Figure 4‑20: Evolution of key landscape elements (Source: Geoffrey Britton, 2015) 70

Figure 4‑21: General view of hallway following floorboard removal, looking east. The former cellar structure is at left of frame (Source: Higginbotham, 1987:6) 71

Figure 4‑22: Footings of a dry-pressed partition wall at the western end of the hallway (Source: Higginbotham, 1987:6) 71

Figure 4‑23: View of cellar, looking northwest. Original joists are at far left and right, with newer (narrower) joists over the cellar (Source: Higginbotham, 1987:7) 72

Figure 4‑24: Entrance hallway, looking north. Original joists in foreground with cellar at extreme left (Source: (Higginbotham, 1987:8) 72

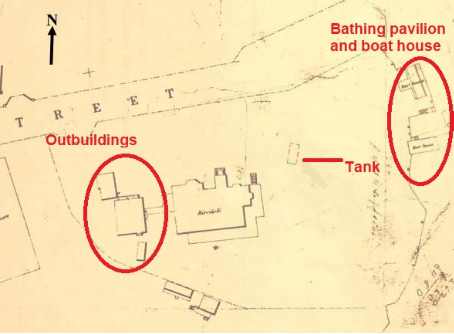

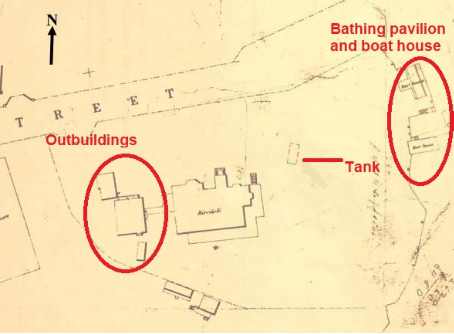

Figure 4‑25: Detail of Metropolitan Water Sewerage & Drainage Board map from 1892 showing features surrounding Kirribilli House (Source: Stanton Library, LH REF MF 299/1, Image #MF2990001) 73

Figure 4‑26: Greenhouse/summer house northeast of main house, undated (Source: Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet) 74

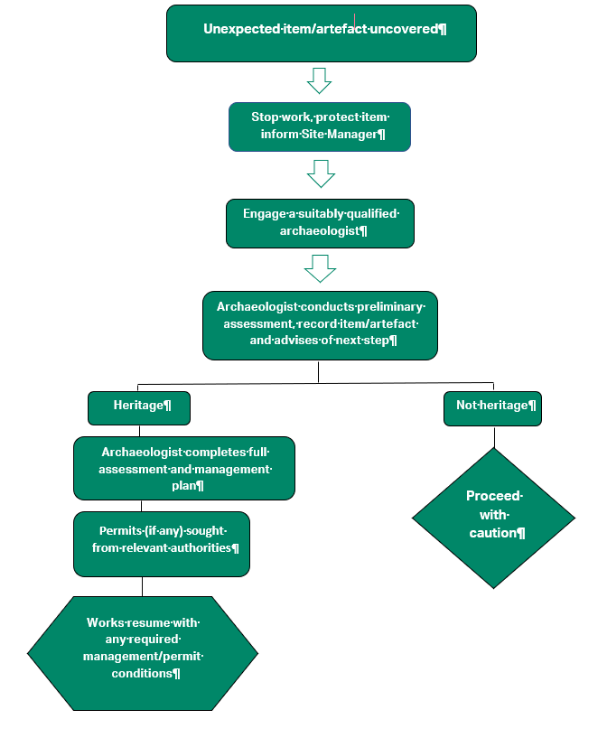

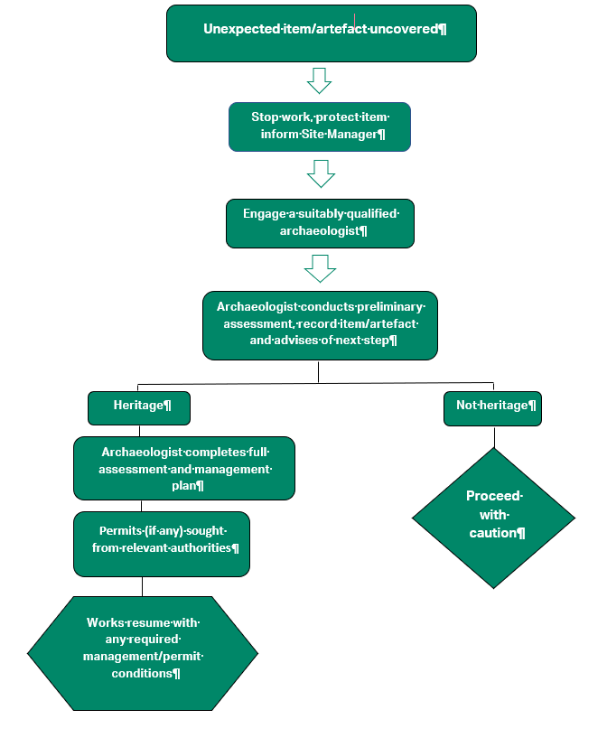

Figure 4‑27: Unexpected finds procedure 75

Figure 5‑1: One of the access paths to Admiralty House and Laundry building on western boundary (AECOM, 2023) 87

Figure 5‑2: Views from the immediate foreshore (AECOM, 2023) 87

Figure 5‑3: Panoramic views (AECOM, 2023) 88

Figure 5‑4: Rock outcrop (AECOM, 2023) 88

Figure 5‑5: Entry gate (AECOM, 2023) 89

Figure 5‑6: c.1913 entry gate (Source: Mitchell Library PXA548—Kirribilli Album) 89

Figure 5‑7: Driveway (AECOM, 2023) 89

Figure 5‑8: 1913 Entry path (Mitchell Library PXA548—Kirribilli Album) 90

Figure 5‑9: Upper eastern grassed banks and terraces (AECOM, 2023) 90

Figure 5‑10: c.1913 (Source: Mitchell Library PXA548 – Kirribilli Album) 91

Figure 5‑11: Lower eastern lawn and eastern walk (AECOM, 2023) 91

Figure 5‑12: 1890s SPF image (Source: Mitchell Library) 91

Figure 5‑13: Northeast gardens (AECOM, 2023) 92

Figure 5‑14: 1900-1902 Northeast Garden (Source: State Library of NSW, W H Davis Manuscript Collection, PXA4467) 92

Figure 5‑15: Northeastern terrace (AECOM, 2023) 93

Figure 5‑16: Clifftop Garden (AECOM, 2023) 93

Figure 5‑17: Foreshore and cliffs (AECOM, 2023) 93

Figure 5‑18: 1890s Foreshore and cliffs (Source: Mitchell Library) 94

Figure 5‑19: Harbourside ruins (AECOM, 2023) 94

Figure 5‑20: 1878 Crown plan showing harbourside structures (1892 plan) 94

Figure 5‑21: Southern lawn terrace and rockeries (AECOM, 2023) 95

Figure 5‑22: Western Garden (AECOM, 2023) 95

Figure 5‑23: Paths and stairs (AECOM, 2023) 96

Figure 5‑24: Significant trees (AECOM, 2023) 96

Figure 5‑25: Victorian Rustic Gothic style 97

Figure 5‑26: North elevation (AECOM, 2023) 97

Figure 5‑27: East elevation (AECOM, 2023) 98

Figure 5‑28: Part south elevation (AECOM, 2023) 98

Figure 5‑29: West elevation (AECOM, 2023) 98

Figure 5‑30: Chimney (AECOM, 2023) 99

Figure 5‑31: Masonry wall (AECOM, 2023) 99

Figure 5‑32: Verandah (AECOM, 2023) 100

Figure 5‑33: Front porch (AECOM, 2023) 100

Figure 5‑34: Bay window (AECOM, 2023) 101

Figure 5‑35: French doors (AECOM, 2023) 101

Figure 5‑36: Original casement window (AECOM, 2023) 102

Figure 5‑37: Timber shutters (AECOM, 2023) 102

Figure 5‑38: Bathroom additions (AECOM, 2023) 103

Figure 5‑39: Service wing (AECOM, 2023) 103

Figure 5‑40: Entry hall (AECOM, 2023) 104

Figure 5‑41: Drawing room (AECOM, 2023) 104

Figure 5‑42: Dining room (AECOM, 2023) 105

Figure 5‑43: Prime Minister’s study (AECOM, 2023) 105

Figure 5‑44: Green room (AECOM, 2023) 106

Figure 5‑45: Hallways and stairs (AECOM, 2023 and painting Witiiti George) 106

Figure 5‑46: Family room (AECOM, 2023) 107

Figure 5‑47: Bedroom 2 (AECOM, 2023) 107

Figure 5‑48: Bathroom (AECOM, 2023) 107

Figure 5‑49: Kitchen (AECOM, 2023) 108

Figure 5‑50: architraves and skirtings (AECOM, 2023 and painting from National Gallery Australia) 108

Figure 5‑51: Subfloor access (AECOM, 2023) 109

Figure 5‑52: Garage (AECOM, 2023) 109

Figure 5‑53: Guard house (AECOM, 2023) 109

Figure 5‑54: Storeroom (AECOM, 2023) 110

Figure 5‑55: Cabinets in hallway (AECOM, 2023 and The Australian Fund) 110

Figure 5‑56: Significance grading of grounds from 2016 HMP (based on Design 5, 2010) updated by AECOM in Table 5-7. 113

Figure 5‑57:Significance grading – vegetation (trees and shrubs) showing results of AECOM tree survey 114

Figure 5‑58: Significance grading First floor plan – Refer to Volume 3 115

Figure 5‑59: Significance grading Roof plan – Refer to Volume 3 115

Figure 5‑60: Significance grading Section – Refer to Volume 3 115

Figure 5‑61: Significance grading North elevation (Design 5, 2010) 115

Figure 5‑62: Significance grading South elevation (Design 5, 2010) 115

Figure 5‑63: Significance grading East elevation (Design 5, 2010) 116

Figure 5‑64: Significance grading West elevation (Design 5, 2010) 116

Figure 5‑65: Significance grading Garage – Volume 3 116

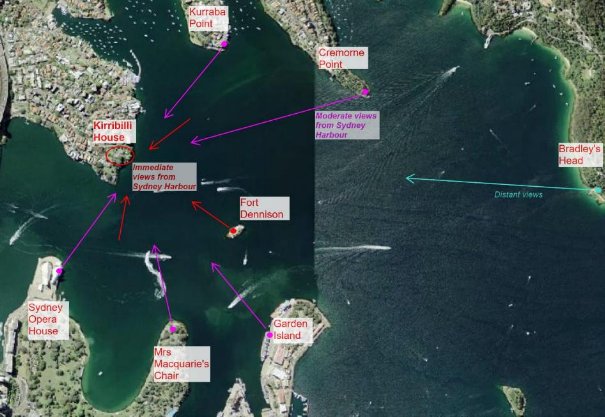

Figure 7‑1: Significant views to Kirribilli House from various vantage points of Sydney Harbour (maps.six.nsw.gov.au 134

Figure 7‑2: Significant views from Kirribilli House and Garden (maps.six.nsw.gov.au) 134

Figure 8‑1: Rising damp to western addition 157

Figure 8‑2: Rising damp adjacent to southern wall outside study 157

Executive Summary

AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM) was commissioned by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) to prepare an updated Heritage Management Plan (HMP) for Kirribilli House at Kirribilli, New South Wales (NSW). This HMP replaces and updates the HMP prepared in 2016, Kirribilli House Operational Heritage Management Plan, Volumes 1 and 2 (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 2016). The HMP has been prepared to meet the obligations of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and to assist PM&C with decisions relating to the care and management of Kirribilli House and Garden.

Kirribilli House and Kirribilli House, Garden and Grounds are separately listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List. Kirribilli House is also listed on Schedule 5 of the North Sydney Local Environmental Plan (LEP) 2013 and the National Trust of Australia.

AECOM have undertaken a review of historical documents and physical assessments through site visits to review and update the heritage significance of Kirribilli House and Garden, which has been re-written as follows.

Statement of significance

Kirribilli House and Garden is highly significant to the Australian cultural history as it has been the official Sydney residence of the Australian Prime Minister since 1957. The site, together with Admiralty House, evidences the early land grants to convict Samuel Lightfoot (1794), Robert Ryan (1800) and Robert Campbell (1806). Kirribilli House and Garden demonstrates the lifestyle of prominent Sydney residents of the Victorian era. The site has direct association with an early public campaign to protect harbourside development in the 1920s. The site has historical significance for its continued association with the Commonwealth role of the Governor-General (Criteria A).

The site is a rare surviving example of a substantial Victorian Rustic Gothic residence in a harbour setting with a significant government use. The bathing pool, although in a ruinous state, has been identified as one of the oldest bathing pools on Sydney Harbour. The site has the potential for archaeology (Criterion B and C).

Kirribilli House and Garden has representative value for its Victorian Rustic Gothic style, as a substantial and harbourside Victorian house. The house and garden are highly significant for aesthetic features. The site has landmark Victorian picturesque qualities and together with Admiralty House and its grounds forms part of a continuous harbour foreshore landscape that is reminiscent of the early Port Jackson shoreline. The Victorian Rustic Gothic style characteristics found at Kirribilli House include the picturesque setting, modest scale, irregular massing, steeply pitched gabled rooves with highly decorated bargeboards, prominent gable, gabled dormer, slate roof, textured masonry walling, bay windows, timber verandah and tall medieval looking chimneys. The garden at Kirribilli House is a representative example of a Victorian garden represented by the picturesque qualities, sweeping lawn, meandering stone paths, terracing, dry stone walling, fencing, dramatic views (panoramic and framed), floristic diversity including leaf form, colour and texture. The harmonious relationship between the house and garden and the contributory architectural elements of the Victorian Rustic Gothic style, contribute to the site’s high aesthetic value (Criterion D and E).

Kirribilli House and Garden is important to the people of Australia. The public have knowledge and respect for the site’s role, that is as the official Sydney residence of the Prime Minister. Their awareness also extends to the understanding of the separate vice regal role of the Governor-General, represented physically by the co-location of Admiralty and Kirribilli Houses. There is an appreciation by the public that Kirribilli House is a modest scale (Criterion G).

Kirribilli House and Garden is significant for its association with Australian Prime Ministers since 1957 and various dignitaries. The garden is associated with Professor E G Waterhouse (linguist, horticulturalist and camellia expert), G W Gillham (head gardener of Admiralty house) and Charles Weston (head of the Yarralumla Nursery in Canberra). The 1957 modifications to the site were undertaken by the well-known architectural firm, Fowell, Mansfield and Maclurcan. The People’s Open Air Space Movement (1920s) along with prominent members of the community including Dr Mary Booth (physician and welfare worker) and Senator H E Pratten (mining entrepreneur and politician) helped protect Kirribilli House from demolition (Criterion H).

The Indigenous heritage assessment did not identify any significant heritage values; however, this would change if future investigations identified cultural modifications of the sandstone outcrops beneath the landscaped garden. This does not negate the fact that the site is located within a broader cultural landscape with intangible cultural values.

Further heritage assessment for potential National and State heritage values have confirmed that Kirribilli House and Garden may meet the criteria for listing in both the National Heritage List (NHL) and State Heritage Register (SHR) and hence should be nominated for listings.

AECOM have incorporated the findings from the Kirribilli House Landscape Management Plan 2020, Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects (Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects Pty Ltd, 2020), undertaken an updated Tree Survey and Indigenous Assessment and consultation for the site. Following this, AECOM have reviewed and updated the heritage management policies and compiled an updated maintenance plan to assist PM&C with the management of the site.

Note: Volume 3 includes redacted material not available to the public due to security requirements.

Kirribilli House is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia, as represented by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C). AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM) was commissioned to prepare an updated Heritage Management Plan (HMP) for Kirribilli House at Kirribilli, New South Wales (NSW) (referred to in this report as ‘the site’, ‘Kirribilli House’, ‘Kirribilli House and Garden’, and the ‘study area’).

The transfer of administration from the Department of Finance to the Department of PM&C took place in 2017. Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), Commonwealth agencies are required to identify, manage, and conserve heritage items. The EPBC Act requires that HMPs are reviewed and updated every five years. This HMP replaces and updates a HMP prepared in 2016, Kirribilli House Operational Heritage Management Plan, Volumes 1 and 2 (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 2016), hereafter referred as, HMP, 2016.

Kirribilli House is located on the Kirribilli peninsula, on the northern foreshore of Sydney Harbour, directly opposite Circular Quay and the Opera House. It is located adjacent to Admiralty House, the Sydney residence of the Governor-General of Australia. The site identification information is presented in Table 1‑1 and the location is shown on Figure 1‑1 and Figure 1‑2.

Table 1‑1: Site Identification Details

Item | Details |

Site Owner | Commonwealth of Australia |

Site Address | 111 Kirribilli Avenue, Kirribilli, NSW |

Legal Description | Lot 109, DP 1151872 |

Zoning | SP2 (infrastructure) Commonwealth Government |

Site Area (m²) | 4,878 m² (approximate) |

A search has been undertaken of the relevant heritage registers (Table 1-2). Kirribilli House and Garden has two separate listings in the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL). It is also listed in Schedule 5 of the North Sydney Local Environmental Plan (LEP) 2013 as an item of local significance within a heritage conservation area.

Table 1‑2: Heritage status - Summary of search results of relevant heritage registers

Register | Listing | Listing Reference |

Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL) | Place ID 105451, Kirribilli House, 111 Kirribilli Avenue, Kirribilli, NSW Place ID 105589, Kirribilli House, Garden and Grounds, 111 Kirribilli Avenue, Kirribilli, NSW | Volume 2 - Appendix A |

National Heritage Listing (NHL) | Nil | n/a |

NSW Heritage Register | Nil | n/a |

North Sydney Local Environmental Plan (LEP) 2013, Schedule 5 (Environmental heritage) Part 1 – Heritage Items | Kirribilli House, Lot 109, DP 1151872, 111 Kirribilli Avenue, Kirribilli Kirribilli Conservation Area | https://www.hms.heritage.nsw.gov.au/App/Item/ViewItem?itemId=2180104 |

National Trust of Australia (NSW) Register | Kirribilli House, Kirribilli Avenue (adjacent to Admiralty House), S8674 | n/a |

The heritage values of Kirribilli House have been outlined in the following previous reports:

- Kirribilli House Operational Heritage Management Plan, Volume 1 and 2, GML (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 2016)

- Kirribilli House Landscape management Plan 2020, Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects (Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects Pty Ltd, 2020)

- Draft Kirribilli House Conservation Management Plan 2010, Design 5 (Design 5, 2010)

- Kirribilli House, Conservation Analysis and Draft Conservation Policy 1985, Clive Lucas & Partners (Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners Pty Ltd, 1986)

- Archaeological Assessment, Kirribilli Foreshore Development, 2000, GML (Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd (GML), 2000)

- Kirribilli House Grounds Conservation and Management Plan 1986, Landscape Architects Department of Housing and Construction (Landscape Architects Department of Housing and Construction, 1986).

The objective of this HMP is to assist PM&C in the management of the assessed heritage values of Kirribilli House. The preparation and implementation of an HMP is required under Section 341S of the EPBC Act for places inscribed on the CHL.

The key issues are:

- Identification and presentation of the Commonwealth, heritage values of Kirribilli House and Garden including historic, natural and Indigenous values

- Provide management policies and guidelines to retain the identified heritage values of Kirribilli House and Garden

- Ensuring that no activities diminish the significance of the setting, form and character of Kirribilli House and Garden

- Ensuring that no activities diminish the main use of Kirribilli House as the Official Sydney residence of the Prime Minister

- Continue to manage and maintain Kirribilli House to a very high standard considering its functional use as the Official Sydney residence of the Prime Minister.

This HMP has been developed to comply with the regulations provided in Schedule 7A and 7B of the EPBC Regulations 2000, which specifies the content of a management plan for CHL places. Table 1‑3 lists the requirements of Schedules 7A and 7B and references the sections of the HMP that address the requirements.

Table 1‑3 EPBC Act Compliance Checklist

Regulation reference | Requirement | Report Section | |

Schedule 7A (a) | Establish objectives for the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Section 1.5 and 1.7 | |

Schedule 7A (b) | Provide a management framework that includes reference to any statutory requirements and agency mechanisms for the protection of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Section 2.0 and 7.0 | |

Schedule 7A (c) | Provide a comprehensive description of the place, including information about its location, physical features, condition, historical context, and current uses | Sections 3.0, 4.0 and Appendix H | |

Schedule 7A (d) | Provide a description of the Commonwealth Heritage values and any other heritage values of the place | Sections 5.0 | |

Schedule 7A (e) | Describe the condition of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Sections 5.4 and Appendix H | |

Schedule 7A (f) | Describe the method used to assess the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Sections 1.7.2 and 1.7.3 | |

Schedule 7A (g) | Describe the current management requirements and goals, including proposals for change and any potential pressures on the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Sections 6.0, 7.1, 7.2 and 7.5.6 | |

Schedule 7A (h) | Have policies to manage the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place, and include in those policies, guidance in relation to the following: |

(i) the management and conservation processes to be used | Section 7.5 | |

(ii) the access and security arrangements, including access to the area for Indigenous people to maintain cultural traditions | Sections 7.6, 7.7.14, 7.7.16 and 7.7.16 | |

(iii) the stakeholder and community consultation and liaison arrangements | Sections 1.6 and 7.5.12 | |

(iv) the policies and protocols to ensure the Indigenous people participate in the management process | Sections 1.8 and 7.7.19 | |

(v) the protocols for the management of sensitive information | Sections 1.6, 2.1 and 7.6 | |

(vi) planning and managing of works, development, adaptive reuse, and property divestment proposals | Sections 5.5, 7.4, 7.5 and 7.7 | |

(vii) how unforeseen discoveries or disturbing heritage values are to be managed | Section 7.7.14 | |

(viii) how, and under what circumstances, heritage advice is to be obtained | Section 7.5 | |

(ix) how the condition of Commonwealth Heritage values is to be monitored and reported | Sections 7.5.1, 7.5.3, 7.5.6 and 7.5.12 | |

(x) how the records of intervention and maintenance of a heritage place’s register are kept | Sections 7.5.1, 7.5.6 and 7.7.9 | |

(xi) research, training, and resources needed to improve management | Sections 7.5.3 and 7.5.4 | |

(xii) how heritage values are to be interpreted and promoted | Sections 7.5.4, 7.7.16, 7.7.18 and 7.7.19 | |

Schedule 7A (i) | Include an implementation plan | Sections 7.5.1 | |

Schedule 7A (j) | Show how the implementation of policies will be monitored | Sections 7.5.6 | |

Schedule 7A (k) | Show how the management plan will be reviewed | Sections 7.5.1 | |

Schedule 7B (1) | The objective in managing Commonwealth Heritage places is to identify, protect, conserve, present and transmit, to all generations, their Commonwealth Heritage values | Sections 5.0 and 7.0 | |

Schedule 7B (2) | The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should use the best available knowledge, skills, and standards for those places, and include ongoing technical and community input to decisions and actions that may have a significant impact on their Commonwealth Heritage values | Sections 7.0 | |

Schedule 7B (3) | The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should respect all heritage values of the place and seek to integrate, where appropriate, any Commonwealth, State, Territory, and local government responsibilities for those places | Sections 2.0 and 7.0 | |

Schedule 7B (4) | The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should ensure that their use and presentation is consistent with the conservation of their Commonwealth Heritage values | Sections 7.5.2 and 7.9 | |

Schedule 7B (5) | The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should make timely and appropriate provision for community involvement, especially by people who: (a) have a particular interest in, or associations with, the place; and (b) may be affected by the management of the place | Sections 7.5.12, 7.7.16 and 7.7.19 | |

Schedule 7B (6) | Indigenous people are the primary source of information on the value of their heritage and that the active participation of Indigenous people in identification, assessment and management is integral to the effective protection of Indigenous heritage values | Sections 1.8, 4.1,7.7.14, 7.7.19 and Appendix J | |

Schedule 7B (7) | The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should provide for regular monitoring, review, and reporting on the conservation of Commonwealth Heritage values | Sections 7.5.1, 7.5.3 and 7.5.6 | |

| | | |

Kirribilli House is owned by PM&C on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia. The roles and responsibilities of Kirribilli House are outlined in Table 1‑4.

Table 1‑4: Stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities for Kirribilli House

Agency | Role and responsibilities |

Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet (PM&C) High Office Support Team (HOST) Section | Ownership and property management of Kirribilli House including heritage management, Capital Works Program, and other ad-hoc projects. PM&C assumed ownership and management of Kirribilli House from the Department of Finance (following the Administrative Arrangements Order of 30 November 2017). |

Jones Lang Lasalle (JLL) | Day to day facilities management and leasing utilising Whole-of-Government service provision arrangements (commenced on 1 March 2023). |

Transport for NSW (Transport) | Transport administers all land below the mean high-water mark in Sydney Harbour. The Commonwealth pays a mooring fee to Transport for the former boat harbour area. |

The Office of the Official Secretary to the Governor-General (OOSGG) | The Laundry and Gardener’s amenities building, located on the southwestern boundary between Kirribilli House and Admiralty House, is on the property of Admiralty House, which is administered by OOSGG. This building is used exclusively by Kirribilli House as a laundry and gardener’s office. There is a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) arrangement with OOSGG for use of the building which also includes the maintenance of the garden at Kirribilli House. |

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | DCCEEW are responsible for legislative compliance of the EPBC Act, provide consultation regarding EPBC Act referrals, prepare submissions based on referrals under the Act for the decision by the Minister and approve EPBC Act referrals. |

In 2017, PM&C assumed ownership and property management of Kirribilli House from the Department of Finance (following the Administrative Arrangements Order of 30 November 2017).

Within PM&C overarching responsibility for Kirribilli House sits with the High Office Support Team (HOST). The Office of the Official Secretary to the Governor-General provides grounds and garden maintenance through a Memorandum of Understanding arrangement; while day-to-day facilities maintenance is provided by Jones Lang Lasalle (JLL) utilising existing Whole-of-Government service provision arrangements (these arrangements commenced on 1 March 2023).

The HOST Section will continue to be responsible for capital works planning and delivery, as well as other ad hoc projects.

To achieve the objectives of an HMP, the following scope of work was undertaken:

- Complete a search of relevant heritage registers

- Review of historical documentation and additional research to fill in knowledge gaps to develop an appreciation of the historical context of the site

- Undertake a site inspection including consultation with Indigenous representatives to understand the physical context of the site

- Assess the heritage values of the site using the relevant Commonwealth criteria

- Undertake a risk assessment to heritage values of the site

- Review and update management policies and develop maintenance activities.

The HMP adheres to the following legislative framework and best practice guidelines:

- EPBC Act and Regulations

- The Australia International Council for Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Charter for Places of Cultural Significance (2013) (the Burra Charter)

- Australian Heritage Council (2010), Identifying Commonwealth Heritage values and Establishing a Heritage Register: A Guide for Commonwealth Agencies

- Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (now Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water [DCCEEW]) Guide: Australia’s Commonwealth Heritage – Working Together – Managing Commonwealth Heritage Places

- Australia Heritage Council, Ask First: A Guide to Respecting Indigenous Heritage Places and Values

- Engage Early: Guidance for Proponents on best practice Indigenous engagement for environmental assessments under the EPBC Act

- Commonwealth of Australia (2002), Australian Natural Heritage Charter.

Consultation with PM&C has determined that the Finance HMP report format is an acceptable template for use.

Australia uses a four-tiered system for identifying significance. A site may be of significance at a World, National, State/Territory or local level.

Items that are deemed significant at a national level must demonstrate they are of significance to the people of Australia as a whole and are listed on the National Heritage List (NHL), an example of which is the Sydney Opera House. To be of State/Territory significance, an item must be of value to the people of that State/Territory, in this case NSW, and listed on the NSW State Heritage Register (SHR). An example would be the General Post Office in Martin Place. Items that may not be of significance at a National or State level but are important to the people of a town or region, may be found in statutory listings on the CHL and the relevant LEP.

The DCCEEW website provides some guidance in assessing the level of significance. To be considered for listing on the CHL, an item must be of at least local significance and have ‘significant’ heritage value against one or more criteria. To meet the threshold for the NHL the place must have ‘outstanding’ heritage value to the nation against one or more criteria. Appendix Q contains further information on the NHL and SHR listings.

The assessment of potential Indigenous, natural and historic heritage significance has been undertaken using the EPBC Act heritage significance criteria, as outlined in Table 1‑5. The assessment was undertaken using the guideline Identifying Commonwealth Heritage Values and Establishing a Heritage Register: A guideline for Commonwealth agencies (Australian Heritage Council, 2010).

Table 1‑5 EBPC Act heritage significance criteria

Criterion A The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s importance in the course or pattern of Australia’s natural or cultural history. |

Criterion B The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s possession of uncommon, rare,

or endangered aspects of Australia’s natural or cultural history. |

Criterion C The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia’s natural or cultural history. |

Criterion D The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of: - A class of Australia’s natural or cultural places; or

- A class of Australia’s natural or cultural environments.

|

Criterion E The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics valued by a community or cultural group. |

Criterion F The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period. |

Criterion G The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural, or spiritual reasons. |

Criterion H The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Australia’s natural or cultural history. |

Criterion I The place has significant heritage value because of the place’s importance as part of Indigenous tradition. |

AECOM have also adopted the Finance significance ranking guide for ease of assessment and consistency with the previous HMP (GML Heritage Pty Ltd, 2016). The ranking system has been developed in reference to the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), Burra Charter, World Heritage Guidelines, Ask First Guideline for Indigenous places, and the Natural Heritage Charter.

Definitions for each category of the ranking system are provided in Table 1‑6 and Table 1‑7. This HMP adopts this ranking system for evaluating heritage significance.

Table 1‑6: Summary of Significance Rankings for Built and Indigenous Heritage

Ranking | Justification- Item | Justification- Precinct/Group | Justification- Intangible |

Exceptional | - The item is a demonstrably rare, outstanding and/or an irreplaceable example of its type

- It has a high degree of intact and original fabric that is readily interpreted

- Loss or alteration would substantively undermine the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

| - The precinct/group demonstrates collective characteristics that are rare or unique in Australia

- Precinct/group is intact and readily interpreted Loss, alteration or removal of component elements would substantially undermine the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

| - The site represents significant social, cultural, natural and/or mythological values that may not be embodied in any physical item but which demonstrate unique, iconic markers in Australia’s past or ongoing dynamic histories and/or processes.

|

High | - The item demonstrates a rare example of its type Is largely intact and interpretable

- Loss or unsympathetic alteration may diminish the cultural heritage values of the item and of the place overall.

| - The precinct/group demonstrates a rare example of collective characteristics or features physically linking or defining the space

- Precinct/group is largely intact and interpretable Loss, unsympathetic alteration or removal of component elements or defining qualities may detract from the cultural heritage values of the precinct/group and of the site overall.

| - The site represents important social, cultural, natural and/or mythological values that may not be embodied in any physical item but which demonstrate rare points in Australia’s past or ongoing dynamic histories and/or processes.

|

Moderate | - The item may have altered or modified elements

- Item is intact enough to be partially interpretable as a single item or as part of the site in its entirety

- Loss or unsympathetic alteration is likely to diminish the cultural heritage values of the item and potentially the place if inappropriately managed.

| - Precinct/group demonstrates valuable (although modified) collective characteristics and linking/defining spatial qualities

- Precinct/group intact enough to be interpreted as a discrete space or as part of the site overall

- Loss, unsympathetic alteration, or removal of component elements or defining qualities may detract from the cultural heritage values of the precinct/group and potentially of the site overall if inappropriately managed.

| - The site represents social, cultural, natural and/or mythological values that may not be embodied in any physical item but which demonstrate points in Australia’s past or ongoing dynamic histories and/or processes.

|

Low | - The item may be largely altered

- Does not demonstrate the key defining qualities of the cultural heritage values but may be contributory

- Alteration and/or modification may make it difficult to interpret the item depending on the existing integrity of the item

- Loss may not diminish the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

| - Precinct/group demonstrates some (but possibly largely altered) collective characteristics and/or linking/defining spatial qualities

- Precinct/group not easily interpreted and represents unclear spatial definition in relation to the rest of the site

- Loss, alteration, or removal of component elements may not detract from the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

| - The site represents some social, cultural, natural and/or mythological values that may not be embodied in any physical item but which demonstrate points in the site’s history, associative values and/or historical themes.

|

None (Does not meet CHL criteria) | - Item does not reflect or demonstrate any cultural heritage values.

| - Precinct/group does not reflect or demonstrate any cultural heritage values.

| - The site represents no social, cultural, natural, or methodological themes or values.

|

Intrusive | - Potentially detracts from the overall Commonwealth heritage values of the place as an intrusive element

- Loss may contribute to the cultural heritage values of the place

- The item is an intrusive element in the heritage values of the place in its entirety.

| - Precinct/group potentially detracts from the interpretation and understanding of the site overall

- Loss, alteration, or removal of component elements actually contribute to the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

| |

Table 1‑7: Summary of Significance Rankings for Natural Heritage Values

Significance Ranking | Justification- Natural |

Exceptional | - The species, area or ecosystem demonstrates individual or collective characteristics that are rare or unique in Australia

- Species, area, or ecosystem is in high level of health, condition and integrity

- Loss, alteration, or removal of component elements would substantially undermine the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

|

High | - The species, area or ecosystem demonstrates a rare example of individual or collective characteristics or features physically linking or defining space

- Species, area, or ecosystem is largely intact and in good state of health;

- Loss, damage, or removal of components or defining qualities may detract from the cultural heritage values of the area or ecosystem and of the site overall.

|

Moderate | - Area or ecosystem demonstrates valuable (although modified) qualities

- Intact enough to be interpreted as a discrete space or as part of the site overall with ability to be regenerated

- Loss, damage, or removal of component elements or defining qualities may detract from the cultural heritage values of the area or ecosystem and potentially of the site overall if inappropriately managed.

|

Low | - Species, area, or ecosystem demonstrates some (but possibly largely altered) defining qualities Area or ecosystem not in a good state of health and regeneration in doubt

- Loss, alteration, or removal of component elements may not detract from the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

|

None (Does not meet CHL criteria) | - Species, area, or ecosystem does not reflect or demonstrate any cultural heritage values.

|

Intrusive | - Loss, alteration, or removal of component elements actually contribute to the cultural heritage values of the place overall.

|

Preliminary review of reports for the site highlighted the following knowledge gaps:

- The heritage significance of the site predominantly lies in the Victorian era and there is insufficient representation of this evidence in the documentary and physical analysis

- Although there are several floor plans available for the site, the original house plans are yet to be located

- Discussion of the significance of the pool and remnant boat shed ruins

- Discussion of the shared history of Admiralty House and the site and why the two sites are separately listed

- Demonstration of the wider landscape context of the harbour setting of the site and critical views and vistas

- Clarity in the process of works approval

- Reliance on the Kirribilli House Landscape Management Plan 2020, Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects (Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects Pty Ltd, 2020) alone is insufficient to demonstrate significance of the landscape elements. This means including information from the HMP, 2016 and previous landscape assessments.

A list of unsolved problems listed in the Kirribilli House, Conservation Analysis and Draft Conservation Policy 1985, Clive Lucas & Partners (Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners Pty Ltd, 1986) are still unanswered. There are likely to be various reasons why they have not been resolved over the past 40 years, one of which is that a number of studies and documents have been produced over this time but were not consolidated, with some documents falling into disuse and thereafter overlooked. This iteration of the HMP has sought to rectify this by consolidating all relevant previous studies and has thus identified the unresolved issues.

Further, some of these issues require physical interventions to fabric and so may only be undertaken opportunistically as part of other works. It is recommended that the next HMP review should start by attempting to solve these issues through additional research. Some of these questions may be answered by detailed physical examination or during physical interventions to the fabric:

- Confirmation of the position and detail of the original staircase

- The detail of the original front door

- The detail of the original bay window on the eastern elevation

- The early detail of the door(s) in the south wall of Study

- The detail of the original verandah

- The detailing of the c.1860s verandah columns and bracket

- Details of the original drawing room windows

- The early use of some of the spaces in the building c.1856-1880

- The exact position, configuration and use of the early outbuildings, c.1856-1920

- The position and thickness of some early internal walls, c.1856-1920

- Specific details about internal decoration, including some chimney pieces and grates

- The detail and configuration of the boat sheds and original staircase down to harbour

- Details of original fencing and gates.

Consultation for this HMP has involved:

- An inception meeting with PM&C stakeholders for overall project

- Consultation with onsite House Manager

- Inception meeting and on-site field inspection with an Indigenous stakeholder relating to Indigenous heritage

- Progress meetings with PM&C, including during site visits.

AECOM consulted with the Indigenous stakeholder groups and representatives outlined in Table 1‑8. The consultation list was derived by writing to agencies, which included Heritage NSW, the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council, the Registrar of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983, the National Native Title Tribunal, Native Title Services Corporation Limited, local council and the catchment management authority, requesting contact details for any relevant Aboriginal groups or individuals. An email inviting expressions of interest and containing summary information on the project was sent to all Aboriginal persons and organisations identified by the regulatory agencies and a total of 16 registrations resulted. Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council cultural officer and archaeologist Rowena Welsh-Jarrett attended the site inspection of Kirribilli House. This was due to security issues necessitating a small core field team for site works. It was reasoned that as the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council was a representative body that had been involved in previous inspections at Kirribilli House, they were the most appropriate group to attend.

Details of the consultation process and Indigenous values are included in Appendix J.

Table 1‑8: Registered Aboriginal Organisations consulted

Organisation | Contact | Date of Registration |

A1 Indigenous Services Pty Ltd | Carolyn Hickey | 22/05/2023 |

Aboriginal Heritage Office, North Sydney Council, Freshwater | Phil Hunt and/or Karen Smith | 1/05/2023 |

Butucarbin | Jennifer Beale | 1/05/2023 |

Darug Custodian Aboriginal Corporation | Justine Coplin | 8/05/2023 |

Didge Ngunawal Clan | Paul Boyd and/or Lilly Carroll | 28/04/2023 |

Ginninderra Aboriginal Corporation | Krystle Carroll Elliott | 2/05/2023 |

Gunjeewong | Shayne Dickson | 2/05/2023 |

Guringai Tribal Link | Paul Craig | 8/05/2023 |

Kamilaroi Yankuntjatjara Working Group | Phil Kahn | 5/05/2023 |

Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council | Rowena Welsh-Jarrett | 9/05/2023 |

Muragadi | Anthony Johnson | 1/05/2023 |

Murrabidgee | Darleen Johnson | 30/04/2023 |

Raw CULTURAL Healing | Raymond Weatherall | 1/05/2023 |

Thomas Dahlstrom (Cultural Heritage Consultant) | Thomas Dahlstrom | 2/05/2023 |

Tocomwall Pty Ltd | Scott Franks | 28/04/2023 |

Wailwan | Phil Boney | 2/05/2023 |

In accordance with paragraph 341(S)(6)(b) of the EPBC Act and 10.03C of the Regulations, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet sought public comments about the matters addressed by the updated HMP by publishing a public notice in 2023 and placing the draft plan on exhibition. No submissions were received in response to this; this document has been finalised following the close of public notification and exhibition.

Given the extensive coverage of the history of Kirribilli House in previous HMPs, limited historical research has been undertaken as part of this HMP. Historical information provided is based on previous reports, principally the 2016 HMP by GML Heritage.

This HMP was prepared by Principal Heritage Architect, Ameera Mahmood with assistance from Senior Heritage Consultant Deborah Farina. The Indigenous assessment was undertaken by ANZ Technical Lead, Dr Darran Jordan, and the Tree and Shrub Survey by Technical Director, Jamie McMahon.

A quality and technical review was also undertaken by Dr Darran Jordan.

AECOM would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance during the preparation of this report:

- Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council representative Rowena Welsh-Jarrett

- The onsite House Manager

Kirribilli House is located on Commonwealth land, hence the primary instruments that are applicable to the subject site are Commonwealth legislation. The PM&C do not need to meet the State or local legislation however, the PM&C Heritage Strategy (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2023a) states that any activities within its properties in principle will aim to comply with the principles set out in the State and local government requirements.

The EPBC Act defines ‘environment’ as both natural and cultural environments and therefore includes Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal historical cultural heritage items. Under the Act, protected heritage items are listed on the NHL (items of significance to the nation) or the CHL (items belonging to the Commonwealth or its agencies). These two lists replaced the Register of the National Estate (RNE), which has been suspended and is no longer a statutory list and so has not had its listings included in this HMP.

The heritage registers mandated by the EPBC Act have been consulted; the site is listed under two listings in the CHL.

Under Part 9 of the EPBC Act, any action that is likely to have a significant impact on a matter of National Environmental Significance (MNES) (known as a controlled action under the EPBC Act),

may only progress with approval of the commonwealth minister responsible for heritage. An action is defined as a project, development, undertaking, activity (or series of activities), or alteration. An action would also require approval if:

- It is undertaken on Commonwealth land and would have or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land; or

- It is undertaken by the Commonwealth and would have or is likely to have a significant impact.

The primary objective of the EPBC Act is to provide for the protection of the environment, particularly those aspects that are MNES. The key parts of the EPBC Act that are of direct relevance to the heritage assessment and management of the Kirribilli House and Garden are:

- Section 26: Requirement for approval of activities involving Commonwealth land with the potential to have a significant impact on the environment

- Section 28: Requirement for approval of activities undertaken by a Commonwealth agency with the potential to have a significant impact on the environment.

Additionally, the EPBC Act also identifies requirements for the protection of Commonwealth Heritage, being:

- Section 341S: Requirement that a Commonwealth agency must make a written plan to protect and manage the Commonwealth Heritage values of a Commonwealth Heritage place it owns or controls (a Heritage Management Plan such as this one)

- Section 341ZC: Requirement to minimise adverse impacts on the heritage values of a place included on the NHL and/or CHL

- Section 341V: Requirement to comply with a plan prepared under Section 341S

- Section 341X: Requirement to review a plan prepared under Section 341S at least once every five years

- Section 341ZE: Requirement to provide ongoing protection of heritage values of a place included on the CHL in the event of sale or transfer.

Sections 26 and 28

The EPBC Act requires actions on Commonwealth land (Section 26) and actions undertaken by a Commonwealth agency (Section 28) to be assessed for the likelihood that these actions will have a significant impact on the environment. The term ‘environment’ has a broader coverage than MNES and relates to environmental matters that are not necessarily formally listed.

The Act defines the environment as:

- Ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities

- Natural and physical resources

- The qualities and characteristics of locations, places, and areas

- Heritage values of places

- The social, economic, and cultural aspects of a thing mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d).

Any actions which will, or are likely, to significantly impact the environment need to be assessed.

If potentially significant impacts are identified, opportunities for their avoidance, reduction or management must be sought. A referral under the EPBC Act may also need to be considered.

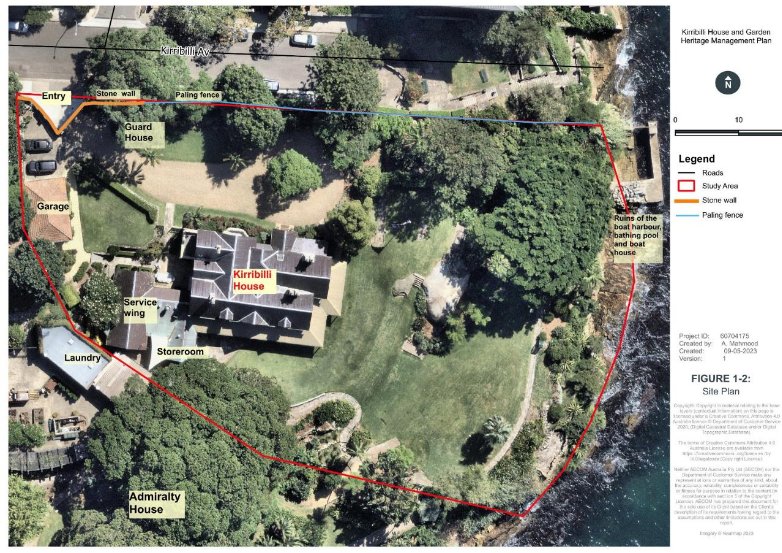

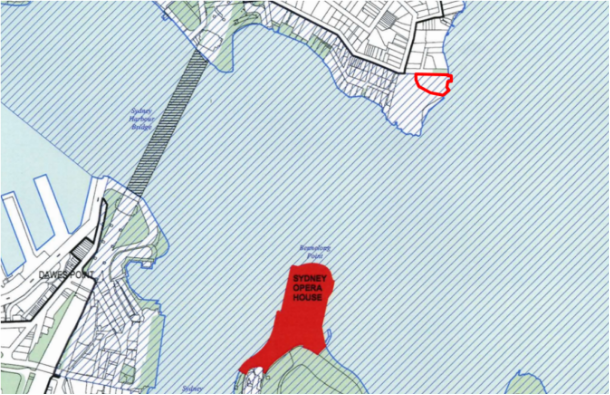

The World Heritage listed Sydney Opera House and its buffer zone are a MNES, thus constituting an additional statutory arrangement that applies to Kirribilli House and Gardens. There is, therefore, a requirement to consider this MNES in relation to any proposed works and ongoing management at Kirribilli House and Gardens. The most likely impact, due to the distance between the two places, is visual, which has been addressed in Section 7.7.4 under Policy 15 for significant views (see also Figure 2‑1).

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (the ATSIHP Act) provides for the preservation and protection of places, areas, and objects of particular significance to Indigenous Australians. The stated purpose of the ATSIHP Act is the “preservation and protection from injury or desecration of areas and objects in Australia and in Australian waters, being areas and objects that are of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition” (Part I, Section 4).

Under the Act, ‘Aboriginal tradition’ is defined as “the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular community or group of Aboriginals, and includes any such traditions, observances, customs or beliefs relating to particular persons, areas, objects or relationships” (Part I, Section 3). A ‘significant Aboriginal area’ is an area of land or water in Australia that is of “particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition” (Part I, Section 3). A ‘significant Aboriginal object’, on the other hand, refers to an object (including Aboriginal remains) of like significance.

For the purposes of the Act, an area or object is considered to have been injured or desecrated if:

- In the case of an area:

- It is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition

- The use or significance of the area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition is adversely affected

- Passage through, or over, or entry upon, the area by any person occurs in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

- In the case of an object:

- It is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

A person must not adversely affect declared significant Aboriginal areas, Aboriginal objects,

or Aboriginal remains.

Duty-of-care notification requirements exist under this Act where a site or artefact is disturbed as

a result of any activity.

The Heritage Act 1977 (Heritage Act) was enacted to conserve the environmental heritage of NSW. Under Section 32, places, buildings, works, relics, movable objects, or precincts of heritage significance are protected by means of either Interim Heritage Orders (IHO) or by listing on the NSW SHR.

Items that are assessed as having State heritage significance can be listed on the NSW State Heritage Register by the Minister on the recommendation of the NSW Heritage Council.

Kirribilli House is not listed on the NSW SHR; however, a preliminary assessment indicates that it may be eligible for listing. However, this is outside the scope of this document.

The Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act) and Environmental Planning & Assessment Regulation 2000 (EP&A Regulation) provides the legislative framework for environmental planning in NSW. The Act and associated regulation include provisions to ensure that all development proposals that have the potential to have an impact on the environment are subject to an appropriate level of assessment, while also providing opportunity for public involvement. This framework is supported by a range of environmental planning instruments including State Environmental Planning Policies (SEPPs) and LEPs.

As a site that is situated on the foreshore of Sydney Harbour, there are relevant sections in the State Environmental Planning Policy (Biodiversity and Conservation) 2021 that are applicable to Kirribilli House. The site can be impacted and can cause an impact to other items of environmental values on the Harbour. Prominent sites include the World heritage listed Sydney Opera House which has a visual buffer zone extending to Kirribilli Point.

Figure 2‑1: Sydney Opera House buffer zone extends to Kirribilli House (circled red) (SREP 2005)

The site is located wholly within the North Sydney Local Government Area (LGA), in which the relevant Environmental Planning Instrument (EPI) is the North Sydney LEP 2013. Clause 5.10 of the North Sydney LEP provides specific provisions for the protection of heritage items and relics within the North Sydney LGA.

Under the North Sydney LEP, development consent is required for any of the following:

- demolishing or moving a heritage item

- altering a heritage item or relic by making structural or non-structural changes to its exterior, such as to its detail, fabric, finish, or appearance

- altering a heritage item by making structural changes to its interior

- moving any relic, or excavating land and discovering, exposing, or moving a relic

- erecting a building on, or subdividing, land on which a heritage item is located.

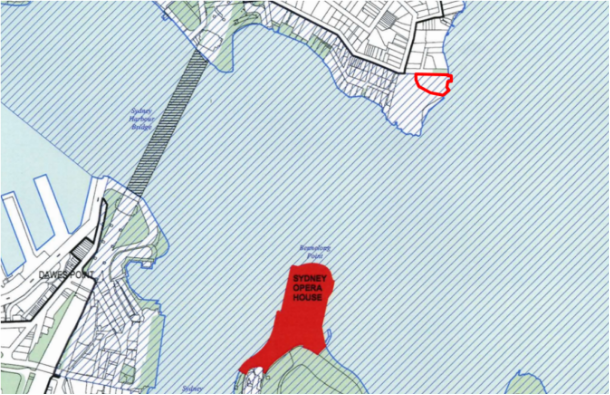

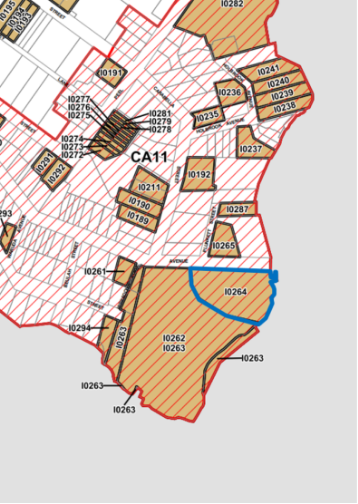

Schedule 5 of the North Sydney LEP 2013 provides a list of heritage items within the North Sydney LGA where the site is listed as “Kirribilli House” (I0264). Kirribilli House is also within the Kirribilli Heritage Conservation Area (CA11).

Figure 2‑2: Extent of Kirribilli Heritage Conservation Area (CA11) in red hatching. Kirribilli House is outlined in blue (Source: NSW Government Planning Portal, North Sydney LEP 2013, Heritage Map 4)

The significance of Kirribilli Conservation Area has been identified in the North Sydney DCP 2013 as:

(a) as a consistent early 20th century residential area with a mix of Federation and one or two storey Inter War dwelling houses and two or three storey residential flat buildings on large allotments with a strong orientation to the water

(b) as a largely intact early 20th century suburb retaining much of the urban detail and fabric seen in gardens, fencing, street formations, use of sandstone and later reinforced concrete “naturale” fencing, sandstone kerbing, natural rock faces, wide streets, and compatible plantings

(c) for its unity derived from its subdivision history which is still clearly seen in the development of the area

(d) as containing the important government buildings Kirribilli House and Admiralty House.

Identified significant elements include the sloping site falling to Sydney Harbour, irregular street pattern and topography as well as views to Sydney Harbour, the Opera House and the City of Sydney.

The National Construction Code (NCC) sets out the legal requirements for building construction in Australia. The main provisions of the Building Code of Australia (BCA) within the NCC include structural requirements, fire resistance, access and egress, services, equipment, health and amenities. The NCC include separate compliance for each State and territory and cites relevant Australian standards.

When considering the BCA requirements in heritage buildings, proposals must ensure that heritage significant fabric and spatial qualities are not compromised. Where proposed works do not meet deemed-to-satisfy provisions, alternative solutions should be sought which might include seeking dispensation for heritage elements or performance-based solutions. Modifications to the site should consider the most sympathetic option to the heritage values of the site.

The Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA) aims to reduce discrimination against people with a disability. The DDA requires that people are given equal opportunity to access public transport and buildings, including those with heritage significance. Clause 11 relating to unjustifiable hardship is particularly relevant to heritage sites:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, in determining whether a hardship that would be imposed on a person (the first person) would be an unjustifiable hardship, all relevant circumstances of the particular case must be taken into account, including the following:

(a) the nature of the benefit or detriment likely to accrue to, or to be suffered by, any person concerned

(b) the effect of the disability of any person concerned

(c) the financial circumstances, and the estimated amount of expenditure required to be made, by the first person

(d) the availability of financial and other assistance to the first person

(e) any relevant action plans given to the Commission under section 64.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, the burden of proving that something would impose unjustifiable hardship lies on the person claiming unjustifiable hardship.

In relation to Kirribilli House, the predominant issues revolve around access throughout the site by staff and visitors. Unjustifiable hardships can include modifications to highly significant fabric. There is opportunity to reach a balance between DDA compliance and a sympathetic solution to the heritage values of the site.

The Burra Charter: The Australian ICOMOS charter for places of cultural significance (ICOMOS (Australia), 2013) sets a standard of practice for those who provide advice, make decisions about,

or undertake works to places of cultural significance including owners, managers and custodians.

The Charter provides specific guidance for physical and procedural actions that should occur in relation to significant places. A copy of the charter can be accessed online at http://icomos.org/australia.

Ask First: A guide to respecting Indigenous heritage places and values (Ask First) was developed by the Australian Heritage Commission (now Australian Heritage Council) to provide a process for Indigenous cultural heritage consultation and management; it has been adopted as the standard approach by Federal government agencies, including Finance. Ask First (Australian Heritage Commission, 2002) recommends a three-stage consultation process:

- Initial consultation

- Identify Traditional Owners

- Meet with relevant Indigenous people to describe the project or activity

- Identifying Indigenous heritage places and values

- Undertake background research

- Ensure that the relevant Indigenous people are actively involved and identify their heritage places and values

- Managing Indigenous heritage places

- Identify any special management requirements with relevant Indigenous people

- Implement and review outcomes with relevant Indigenous people and other stakeholders.

The consultation process outlined in Section 1.8 was undertaken in accordance with these guidelines.

Engage Early: Guidance for proponents on best practice Indigenous engagement for environmental assessments under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) (Engage Early) was developed by the Commonwealth of Australia, 2016 and should be read in conjunction with Ask First (refer to Section 2.4.2). Engage Early provides framework for an early and cooperative approach for how proponents should engage and consult with Indigenous peoples during the environmental assessment process under the EPBC Act.

The framework for what is considered to be best practice consultation includes:

- The early identification and acknowledgement of all relevant Indigenous peoples and communities

- Building trust by early and ongoing engagement, commitment, and clarity

- Being aware of statutory processes regarding consultation and consent processes

- Establishing appropriate timeframes for consultation