Family: Psittacidae

Current status of taxon

- Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth): Critically Endangered

- Nature Conservation Act 2014 (Australian Capital Territory): Critically Endangered

- Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (New South Wales): Endangered

- Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland): Endangered

- National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia): Endangered

- Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (Tasmania): Endangered

- Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victoria): Critically Endangered

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Critically Endangered

Distribution and habitat

The Swift Parrot breeds mostly on the east and south-east coast of Tasmania during summer and migrates to mainland Australia in autumn. During winter the species disperses across forests and woodlands, foraging on nectar and lerps mainly in Victoria and New South Wales. Small numbers of Swift Parrots are also recorded in the Australian Capital Territory, south eastern South Australia and southern Queensland. The area occupied during the breeding season varies between years, depending on food availability, but is typically less than 500 km2.

Recovery plan vision, objective and strategies

Long-term vision

The Swift Parrot population has increased in size to such an extent that the species no longer qualifies for listing as threatened under any of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 listing criteria.

Recovery Plan objective

- By 2032, maintain or improve the extent, condition and connectivity of habitat of the Swift Parrot.

- By 2032, anthropogenic threats to Swift Parrot are demonstrably reduced.

- By 2032, measure and sustain a positive population trend.

This will be achieved by implementing the actions set out in this Recovery Plan that minimise threats while protecting and enhancing the species’ habitat throughout its range, adequately monitoring the species, generating new knowledge to guide recovery and increasing public awareness.

Strategies to achieve objective

- Maintain known Swift Parrot breeding and foraging habitat at the local, regional and landscape scales.

- Reduce impacts from Sugar Gliders at Swift Parrot breeding sites.

- Monitor and manage other sources of mortality.

- Develop and apply techniques to measure changes in population trajectory in order to measure the success of recovery actions.

- Improve understanding of foraging and breeding habitat use at a landscape scale in order to better target protection and restoration measures.

- Engage community and stakeholders in Swift Parrot conservation.

- Coordinate, review and report on recovery progress.

Criteria for success

This recovery plan will be deemed successful if, by 2032, all of the following have been achieved:

- the Swift Parrot population has a positive ongoing population trend, as a result of recovery actions

- there has been an improvement in the quality and extent of Swift Parrot habitat throughout the species’ range

- understanding of the species’ ecology has increased, in particular knowledge of movement patterns, habitat use and post-breeding dispersal

- there is increased participation by key stakeholders and the public in recovery efforts and monitoring.

Recovery team

Recovery teams provide advice and assist in coordinating actions described in recovery plans. They include representatives from organisations with a direct interest in the recovery of the species, including those involved in funding and those participating in actions that support the recovery of the species. The national Swift Parrot Recovery Team has the responsibility of providing advice, coordinating and directing the implementation of the recovery actions outlined in this recovery plan. The membership of the national Recovery Team should include representatives from relevant government agencies, non-government organisations, industry groups, species experts and expertise from independent researchers and community groups.

This document constitutes the National Recovery Plan for the Swift Parrot (Lathamus discolor). The plan considers the conservation requirements of the species across its range and identifies the actions needed to improve the species’ long-term viability. This recovery plan supersedes the 2011 National Recovery Plan for the Swift Parrot (Saunders and Tzaros 2011).

The Swift Parrot is listed as Critically Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). It was listed as Endangered under the EPBC Act in 2000, however the listing status of the Swift Parrot was re-assessed in 2016 due to new information showing a significant threat from predation of females and nestlings by the introduced (to Tasmania) Sugar Glider (Petaurus breviceps) (Stojanovic et al. 2014).

Sugar Glider impacts in Tasmania are compounding and adding to the already recognised threats to the Swift Parrot, including habitat loss and alteration and Australia’s changing climate. The re-assessment concluded that the risk posed by this previously unidentified threat was significant enough to justify moving the species from the Endangered category to the Critically Endangered category of the EPBC Act list of threatened species. The re-assessment also concluded that the recovery plan should be updated to include measures to reduce the impact of Sugar Gliders.

The 2011 Recovery Plan was reviewed by the Swift Parrot Recovery Team in 2016–2017. The review concluded that despite increases in knowledge across a range of domains and progress implementing many of the actions, the plan’s overall objective has not been achieved and ‘that there were ongoing declines in the number of mature individuals, and in the area and quality of habitat available for the species, including clearing of breeding habitat’. Of 28 specific actions in the plan, at the time of the review: seven were considered not to have commenced or had otherwise made only minimal progress; some progress had been made for 14 actions; and seven were identified as completed and/or ongoing.

Overall the review found that population trend information for Swift Parrots remained uncertain, as there was no estimate of population size or equivalent indices that could be used to estimate a population trend. However, based on modelling of known reproductive success parameters and predation by Sugar Gliders, it was demonstrated that the population was likely declining.

The review also concluded that at the time of writing the 2011 Recovery Plan, the Sugar Glider threat was not recognised and that, as a result, the plan was lacking any recovery actions to address that threat. The review concluded that a new recovery plan should be developed for the Swift Parrot to account for predation by Sugar Gliders and address the ongoing loss of breeding habitat in Tasmania.

The accompanying Species Profile and Threats Database (SPRAT) provides additional background information on the biology, population status and threats to the Swift Parrot. SPRAT pages are available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl

The Swift Parrot is listed as Critically Endangered under the EPBC Act, and listed threatened in all parts of its range (Table 1). The last 20 years of Swift Parrot conservation have shown that conservation efforts have been insufficient to halt the species’ decline. Despite extensive outreach to the public and policy makers, conservation management has not kept pace with advances in knowledge and scientific evidence (Webb et al. 2019). While some Swift Parrot habitat has been protected in conservation reserves in Tasmania and mainland states, and some timber harvesting prescriptions imposed to moderate the impact of forestry, such as the Public Authority Management Agreement covering the Southern Forests in Tasmania, there remain many unresolved challenges for habitat protection. Sugar Glider impacts in Tasmania are worst where habitat loss is severe, which compounds the effects of forestry operations (Stojanovic et al. 2014). Climate change poses an additional threat to the species, but its consequences are poorly studied. If habitat continues to be lost across the species’ range, and Sugar Glider predation is not addressed, the species will likely continue its downward trajectory and become extinct in the wild.

Table 1 National and state conservation status of the Swift Parrot

Legislation | Conservation status |

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) | Critically Endangered |

Nature Conservation Act 2014 (Australian Capital Territory) | Critically Endangered |

Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (New South Wales) | Endangered |

Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland) | Endangered |

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia) | Endangered |

Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victoria) | Critically Endangered |

Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (Tasmania) | Endangered |

The Swift Parrot (White 1790) is a small fast-flying, nectarivorous parrot which occurs in eucalypt forests in south eastern Australia. Bright green in colour, the Swift Parrot has patches of red on the throat, chin, face and forehead, which are bordered by yellow. It also has red on the shoulder and under the wings and blue on the crown, cheeks and wings. A distinctive call of pip-pip-pip (usually given while flying), a streamlined body, long pointy tail and flashes of bright red under the wing enable the species to be readily identified.

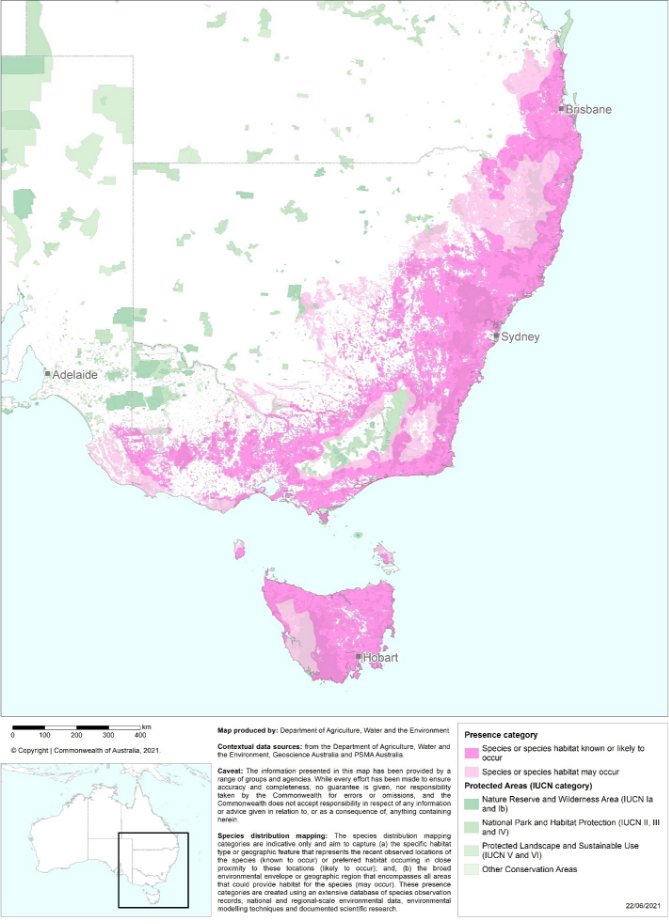

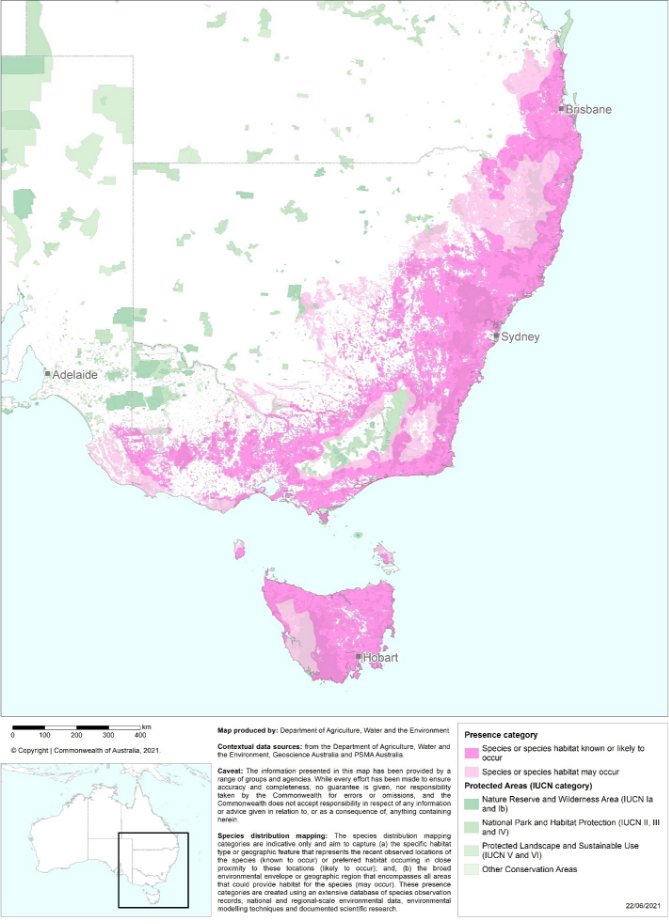

The Swift Parrot breeds in Tasmania during the summer and migrates north to mainland Australia for winter (Figure 1). The breeding range of the Swift Parrot is mainly in the east and south-east regions of Tasmania (Figure 2), with the location of breeding each year being determined largely by the distribution and intensity of Blue Gum (Eucalyptus globulus) and Black Gum (E. ovata) flowering (Webb et al. 2014). The flowering patterns of these species varies dramatically in location and extent between years (Webb et al. 2017). Swift Parrots also occasionally breed in the north-west of the state, between Launceston and Smithton, however, the number of birds involved is low, probably because the remaining breeding habitat is scarce and highly fragmented. Swift Parrots have also been found breeding on the west coast of Tasmania near Zeehan, and on King and Flinders Islands (M. Webb unpublished data).

Swift Parrots disperse widely on the mainland, foraging on flowers and lerps in eucalyptus species, mainly in Victoria and New South Wales. In Victoria, Swift Parrots are predominantly found in the dry forests and woodlands of the box-ironbark region on the inland slopes of the Great Dividing Range. There are a few records each year from the Melbourne and Geelong districts and they are occasionally recorded south of the divide in the Gippsland region.

In New South Wales, Swift Parrots forage in forests and woodlands throughout the coastal and western slopes regions each year. Coastal regions in New South Wales tend to support larger numbers of birds when inland habitats are subjected to drought, as occurred in 2002 and 2009 (Tzaros et al. 2009).

Small numbers of Swift Parrots are observed in the Australian Capital Territory and in south-eastern Queensland on a regular basis. The species is less frequently observed in the Southern Mount Lofty Ranges and the Bordertown-Naracoorte area in south-eastern South Australia (Saunders and Tzaros 2011).

The Swift Parrot occurs as a single, panmictic migratory population (Stojanovic et al. 2018). In 2010, the Action Plan for Australian Birds suggested there were approximately 2,000 mature individuals in the wild (Garnett et al. 2011), but has declined since and was estimated to be 750 (range 300 to 1,000) mature individuals in 2020 (Webb et al. 2021). A preliminary study using genetic data has estimated the effective population size (Ne) of the Swift Parrot to be between 60 and 338 individuals (Olah et al. 2020) noting that Ne is a parameter commonly used in population genetics to quantify loss of genetic variation in populations and it is often smaller than the census population size (Nc) (e.g. Wang et al. 2016).

While the current population size is uncertain, recent research has shown it is likely undergoing dramatic declines due to predation by Sugar Gliders (Heinsohn et al. 2015). Sugar Gliders are an introduced species to Tasmania (Campbell et al. 2018), and their impacts on Swift Parrots compound and add to other known threats including habitat loss and degradation. Stojanovic et al. (2014) found that Swift Parrot nests failed at a very high rate on the Tasmanian mainland, compared to no failure on offshore islands where Sugar Gliders were absent. Most cases of glider predation resulted in the death of the adult female, and always involved the death of either eggs or nestlings.

Heinsohn et al. (2015) constructed a population viability analysis (PVA) using demographic data gained from the Sugar Glider predation study and population monitoring (Stojanovic et al. 2014; Webb et al. 2014). Five scenarios were considered in the PVA. The first scenario was based on field data from Bruny and Maria Islands, which are both Sugar Glider free. This scenario estimated growth rates in the absence of Sugar Glider predation and projected a substantial increase in numbers over time. Four other PVA models were tested which accounted for Sugar Glider predation but used different generation times for Swift Parrots.

The mean decline over the four scenarios that included Sugar Glider predation was projected at 86.9 per cent (range over the four models was 78.8 to 94.7 per cent decline) over three generations. The preferred model by Heinsohn et al. (2015) projected that Swift Parrots would undergo an extreme decline of 94.7 per cent within a three-generation period. This model used a generation time of 5.4 years, which was obtained through expert elicitation (Garnett et al. 2011).

While research has found that that breeding success is much higher on Sugar Glider free islands (Stojanovic et al. 2014), this greater success was insufficient to buffer the population against collapse under the modelled scenarios (Heinsohn et al. 2015). More recent evidence shows that high predation by Sugar Gliders at some breeding sites has resulted in a change to the Swift Parrot mating system due to the rarity of adult females, resulting in even worse projected population declines based on PVA (Heinsohn et al. 2019).

Figure 1 Indicative distribution of the Swift Parrot in Australia

Figure 2 Potential breeding range of Swift Parrot in Tasmania

Note: Swift Parrot Important Breeding Areas (SPIBA) are known or suspected to have supported a large portion of the Swift Parrot breeding population in any given year (FPA 2010). The core range of the Swift Parrot is the area within the south-eastern (SE) potential breeding range that is within 10 km of the coast or is designated as a SPIBA (as defined in FPA 2022). The potential breeding range of the Swift Parrot comprises the north-western (NW) potential breeding range and the SE potential breeding range. The NW potential breeding range includes the NW breeding areas (known nesting locations such as, Gog Range, Badger Range, Kelcey Tier) (FPA 2022).

Swift Parrots spend the winter on mainland Australia (Figure 1). During the non-breeding season the population frequents eucalypt woodlands and forests in South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory and Queensland. Within these habitats, Swift Parrots preferentially forage in large, mature trees (Kennedy 2000; Kennedy and Overs 2001; Kennedy and Tzaros 2005) that provide more reliable foraging resources than younger trees (Wilson and Bennett 1999; Law et al. 2000).

Key foraging species includes Yellow Gum (E. leucoxylon); Red Ironbark (E. tricarpa); Mugga Ironbark (E. sideroxylon); Grey Box (E. macrocarpa); White Box (E. albens); Yellow Box (E. melliodora); Swamp Mahogany (E. robusta); Forest Red Gum (E. tereticornis); Blackbutt (E. pilularis); and Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata). Other foraging species may be important at certain times of the year. Swift Parrots rely heavily on lerp for food. Lerps are protective covers made by nymphs (a larval stage that resembles adults) of jumping plant lice or psyllids (Family: Psyllidae). Nymphs excrete honeydew on the leaf surface and the sugars and amino acids in the honeydew crystallise in the air to form lerps. Leaves can look black and sooty when moulds grow on the honeydew. Lerp size and shape varies between species of psyllid. On mainland Australia Swift Parrots are regularly found feeding on lerp, with flocks of up to 50 birds feeding on lerp for up to an entire season, sometimes choosing to eat lerp despite the nearby availability of nectar resources (S. Vine BirdLife Australia pers. comm.).

The distribution of Swift Parrots across the landscape will vary depending on the flowering phenology of key foraging species. Due to the variable production of nectar and lerps it is considered critically important to protect and manage a broad range of habitats to provide a range of foraging resources (Kennedy and Overs 2001; Kennedy and Tzaros 2005).

1.5.2 Tasmanian breeding and foraging habitat

Breeding records for Swift Parrots are largely restricted to the south and east coast of Tasmania, including Bruny and Maria islands, with some sporadic breeding occurring in the north of the state (Figure 2). The distribution of nesting Swift Parrots each breeding season is determined largely by the distribution and intensity of Blue Gum (E. globulus) and Black Gum (E. ovata) flowering (Webb et al. 2014). The flowering patterns of these species varies dramatically in location and extent over annual cycles (Webb et al. 2017). The flowering patterns of other potential forage eucalypt species, including Brooker’s Gum (E. brookeriana), may also be important determinants of Swift Parrot breeding distribution.

Swift Parrots nest in any eucalypt forests and woodlands which contain tree hollows, provided that flowering trees are nearby (Webb et al. 2017). Nesting occurs in the hollows of live and dead eucalypt trees. There is no evidence that suggests Swift Parrots prefer any particular tree species for nesting, instead, the traits of tree cavities are the main factor that predicts whether a tree is used as a nest (Stojanovic et al. 2012). Nest sites have been recorded in a range of dry and wet eucalypt forest types, and Swift Parrots exhibit little preference for vegetation communities, and instead respond to the configuration of resources in the landscape (Webb et al. 2014; 2017).

Nest trees are typically characterised by having a diameter at breast height of around 80 cm or greater, several visible hollows and showing signs of senescence (Webb et al. 2012; Stojanovic et al. 2012). Eucalypt trees in Tasmania usually take at least 100 years to form hollows, and at least 140 years to form deeper hollows (Koch et al. 2008). However, some nest trees can be smaller, or much larger, and tree size varies between forest types. The tree hollows preferred for nesting have small entrances (~5 cm), deep chambers (~40 cm) and ~12 cm wide floor spaces (Stojanovic et al. 2012). These traits are rare, and only 5 per cent of tree hollows in a given forest area may meet these criteria. Suitable hollows are important because they act as a passive form of nest defence against native Tasmanian nest predators, but these defences are ineffective against Sugar Gliders (Stojanovic et al. 2017).

The prevalence of hollows in eucalypt forests and woodlands and close proximity to a foraging resource is considered more important than forest type and/or tree species in determining where Swift Parrot nests occur. Where suitable hollows are available, nest sites can be found in all topographic positions and aspects (Webb et al. 2012).

Swift Parrots reuse nesting sites and individual nest hollows over different years (Stojanovic et al. 2012) and this highlights the importance of nesting areas for the species' long-term viability. The presence of a foraging resource influences whether an area is suitable on a year-to-year basis (Webb et al. 2014).

Blue Gum and Black Gum forests and any other communities where Blue Gum or Black Gum is subdominant (e.g. wet eucalypt forests, dry eucalypt forests, forest remnants and paddock trees) are important foraging habitats (Webb et al. 2014; 2017). From one season to the next, Blue Gum or Black Gum may comprise the primary foraging resource. Planted Blue Gums (e.g. street and plantation trees) may provide a temporary local food resource in some years, noting that plantation Blue Gum are unlikely to provide substantial forage resources due to age, tree density and genetic strain (FPA 2014).

Generally, the larger the tree the more foraging value it has for Swift Parrots. Brereton et al. (2004) demonstrated a greater flowering frequency and intensity in larger Blue Gums and a preference by Swift Parrots to forage in these larger trees. During the breeding season, Swift Parrots often feed on lerps, wild fruits such as Native Cherry (Exocarpos cupressiformis) and the seeds of introduced eucalypts and callistemon species. The relative importance of these other food sources during the breeding season is not well understood.

Non-breeding dispersal and post-breeding habitat can be anywhere in Tasmania, including forests in the west and north-west. The species has been observed feeding on flowering Stringybark, Gum-topped Stringybark, White Gum, Mountain Gum (E. dalrympleana), Cabbage Gum (E. pauciflora) and Smithton Peppermint (E. nitida) (Swift Parrot Recovery Team 2001).

Birds arrive in Tasmania in early August and breeding occurs between September and January. Both sexes search for suitable nest hollows, which begins soon after birds arrive in Tasmania. Nesting commences in late September, however but birds that are unpaired on arrival in Tasmania may not begin nesting until November, after they have found mates (Brown 1989). Gregarious by nature, pairs may nest in close proximity to each other and even in the same tree (Stojanovic et al. 2012; Webb et al. 2012).

The female occupies the nest chamber for several weeks before egg laying and she undertakes all of the incubation and brooding until nestlings are sufficiently developed. The mean clutch size is 3.8 eggs but up to six eggs may be laid, and the mean number of fledglings produced is 3.2 (Stojanovic et al. 2015). During incubation the male visits the nest site every three to five hours to feed the female. The male perches near the nest and calls the female out, either feeding her at the nest entrance or after both birds fly to a nearby perch.

Reproductive success is strongly influenced by the availability and intensity of Blue and/or Black Gum flowering, and nest site selection with regard to the presence of Sugar Gliders. In years where birds breed primarily on Bruny and Maria Islands, breeding success is much higher as Sugar Gliders are not found on these islands (Stojanovic et al. 2014, 2015). Swift Parrots moderate the impact of local fluctuations in food availability by nesting wherever food abundance is high, and so have relatively low variation in the number or quality of nestlings produced between different years and breeding sites (Stojanovic et al. 2015).

Male Swift Parrots provision their nestlings using food resources that typically occur within 5 km of their nests, but the further they fly to feed, the poorer their overall reproductive success may become (Stojanovic et al. in review). Evidence from telemetry shows that in years where food is abundant, provisioning males may forage within 1 km of the nest, whereas when food is scarce trips up to 9 km from the nest have been recorded (Stojanovic et al. in review).

Swift Parrots sometimes utilise artificial nesting sites, however occupancy of nest boxes is highest when nearby natural nesting sites are saturated with Swift Parrots, and nest boxes are a second preference for nesting (Stojanovic et al. 2019).

The Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) program aims to identify, map, monitor and conserve the critical sites for global biodiversity across the planet. This is a non-statutory process guided by a Global Standard for the Identification of Key Biodiversity Areas, the KBA Standard (IUCN 2016). It establishes a consultative, science-based process for the identification of globally important sites for biodiversity worldwide. Sites qualify as KBAs of global importance if they meet one or more of 11 criteria in five categories: threatened biodiversity; geographically restricted biodiversity; ecological integrity; biological processes; and, irreplaceability. The KBA criteria have quantitative thresholds and can be applied to species and ecosystems in terrestrial, inland water and marine environments. These thresholds ensure that only those sites with significant populations of a species or extent of an ecosystem are identified as global KBAs. Species or ecosystems that are the basis for identifying a KBA are referred to as Trigger species.

The global KBA partnership supports nations to identify KBAs within their country by working with a range of governmental and non-governmental organisations scientific species experts and conservation planners. Defining KBAs and their management within protected areas or through Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) will assist the Australian Government to meet its obligations to international treaties, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity. KBAs are also integrated in industry standards such as those applied by the Forest Stewardship Council or the Equator Principles adopted by financial institutions to determine environmental risk in projects.

The initial identification of a site as a KBA is tenure-blind and unrelated to its legal status as it is determined primarily based on the distribution of one or more Trigger species at the site. However, existing protected areas or other delineations such as military training area or a commercial salt works will often inform the final KBA delineation, because KBAs are defined with site management in mind (KBA Standards and Appeals Committee 2019). In practice, if an existing protected area or other designation roughly matches a KBA, it will generally be used for delineating the KBA. Many KBAs overlap wholly with existing protected area boundaries, including sites designated under international conventions (e.g. Ramsar and World Heritage) and areas protected at national and local levels (e.g. national parks, Indigenous or community conserved areas). However, not all KBAs are protected areas and not all protected areas are KBAs. It is recognised that other management approaches may also be appropriate to safeguard KBAs. In fact, research from Australia and elsewhere demonstrates the value of OECMs in conserving KBAs and their Trigger species (Donald et al. 2019) if the site is managed appropriately. The identification of a site as a KBA highlights the sites exceptional status and critical importance on a global scale for the persistence of the biodiversity values for which it has been declared for (particular Trigger species or habitats) and implies that the site should be managed in ways that ensure the persistence of these elements. For more information on KBAs visit http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/home

The global KBA partnership currently recognises 18 KBAs as important for Swift Parrot conservation and to support the long-term persistence of the species. KBAs are also undergoing a regular revision to ensure changes in IUCN red list status, taxonomic changes, local population trends as well as increased knowledge of the species are reflected accurately in the KBA network. As such, over time, additional KBAs may be recognised for their importance for Swift Parrot or new KBAs may be declared for this and other taxa. Detailed KBA Factsheets, including boundary maps, population estimates of trigger species and scientific references are for these 18 areas (and other KBAs) are available from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas (BirdLife International 2020). The 18 KBAs with Swift Parrot as one of their Trigger species were also recognised prior to the introduction of the KBA standard as Important Bird Areas for the species in 2009 based on the analysis by BirdLife Australia. They include:

New South Wales

- Brisbane Water – Brisbane Water is a wave-dominated barrier estuary located in the Central Coast region, north of Sydney, New South Wales. Some 2,277 hectares of Brisbane Water is classified as KBA because it has an isolated population of Bush Stone-curlews and supports flocks of the Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeater and Swift Parrot during autumn and winter, when the Swamp Mahogany trees are in flower.

- Capertee Valley – The Capertee Valley is the second largest canyon (by width) in the world and largest valley in New South Wales, 135 km north-west of Sydney. Parts of the valley are included in the Wollemi National Park, the second-largest national park in New South Wales. The valley is classified as a KBA because it is the most important breeding site for the Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeater. It also supports populations of the Painted Honeyeater, Rockwarbler, Swift Parrot, Plum-headed Finch and Diamond Firetail.

- Hastings-Macleay – The Hastings-Macleay KBA is a 1,148 km2 tract of land stretching for 100 km along the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, from Stuarts Point in the north to the Camden Haven River in the south. The area was identified by BirdLife International as an KBA because it regularly supports significant numbers of the Critically Endangered Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater.

- Hunter Valley – The Hunter Valley KBA is a 560 km2 tract of land around Cessnock in central-eastern New South Wales. The site has been identified as a KBA because it regularly supports significant numbers of the Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeater and Swift Parrot. The KBA is defined by remnant patches of eucalypt-woodland and forest used by the birds in a largely anthropogenic landscape. It includes Aberdare and Pelton State Forests, Broke Common, Singleton Army Base, Pokolbin, Quorrobolong, Abermain and Tomalpin, as well as various patches of bushland, including land owned by mining companies. The KBA contains Werakata National Park and part of Watagans National Park.

- Lake Macquarie – Lake Macquarie is Australia's largest coastal salt water lake. Located in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, it covers an area of 110 km2 and is connected to the Tasman Sea by a short channel. The remnant and fragmented eucalypt forests on the southern margins of the lake have been identified as a 121 km2 KBA because they support significant numbers of Critically Endangered Swift Parrots and Regent Honeyeaters in years when the Swamp Mahogany and other trees are flowering.

- Richmond Woodlands – The Richmond Woodlands comprise some 329 km2 of eucalypt woodland remnants close to Richmond, New South Wales. They lie at the foot of the Blue Mountains on the north-western fringe of the Sydney metropolitan area. The KBA boundary is defined by patches of habitat suitable for Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeaters and Swift Parrots, centred on the woodlands between the Agnes Banks, Windsor Downs and Castlereagh Nature Reserves, and extending south to Penrith and north-east to encompass Scheyville National Park. It is adjacent to the forested hills of the Greater Blue Mountains KBA.

- South-west Slopes of New South Wales – An area of 25,653 km2, largely coincident with the bioregion, has been identified as a KBA because it supports a significant wintering population of the Critically Endangered Swift Parrots and Vulnerable Superb Parrots (Polytelis swainsonii), as well as populations of Painted Honeyeaters and Diamond Firetails. Most of the site is modified wheat-growing and sheep-grazing country with only vestiges of its original vegetation. Remnant patches of woodland and scattered large trees, especially of Mugga Ironbark (E. sideroxylon), Apple Box (E. bridgesiana), Grey Box (E. microcarpa), White Box (E. albens), Yellow Box (E. melliodora), Red Box (E. polyanthemos), Yellow Gum (E. leucoxylon), River Red Gum and Blakely's Red Gum (E. blakelyi), still provide habitat for the Painted Honeyeaters. Protected areas within the site include several nature reserves and state forests, as well as the Livingstone and Weddin Mountains National Parks, and Tarcutta Hills Reserve.

- Tuggerah – The Tuggerah Lakes, a wetland system of three interconnected coastal lagoons, are located on the Central Coast of New South Wales, Australia and comprise Lake Munmorah, Budgewoi Lake and Tuggerah Lake. The adjacent forests and woodlands provide habitat for Swift Parrots and Regent Honeyeaters in the non-breeding season.

- Ulladulla to Merimbula – The Ulladulla to Merimbula KBA comprises a strip of coastal and subcoastal land stretching along the southern coastline of New South Wales. It is an important site for Swift Parrots. The 2,100 km2 KBA extends for about 250 km between the towns of Ulladulla and Merimbula and extends about 10 km inland from the coast. It is defined by the presence of forests, or forest remnants, of Spotted Gum and other flowering eucalypts used by Swift Parrots. It includes forests dominated by ironbarks and bloodwoods which are likely to support Swift Parrots in years when the Spotted Gums are not flowering. The KBA either encompasses, or partly overlaps with, the Ben Boyd, Biamanga, Bournda, Clyde River, Eurobodalla, Gulaga, Meroo, Mimosa Rocks, Murramarang and South East Forest National Parks.

Victoria

- Bendigo Box-Ironbark Region – The Bendigo Box-Ironbark Region is a 505 km2 fragmented and irregularly shaped tract of land that encompasses all the box-ironbark forest and woodland remnants used as winter feeding habitat by Swift Parrots in the Bendigo-Maldon region of central Victoria. The site lies between the Maryborough-Dunolly Box-Ironbark Region and Rushworth Box-Ironbark Region KBAs. It includes much of the Greater Bendigo National Park, several nature reserves and state forests, with a few small blocks of private land. It excludes other areas of woodland that are less suitable for Swift Parrots. The region was identified as an KBA because, when flowering conditions are suitable it supports up to 50 per cent of the global population of non-breeding Swift Parrots.

- Maryborough-Dunolly Box-Ironbark Region – The Maryborough-Dunolly Box-Ironbark Region includes all the box-ironbark forest and woodland remnants used as winter feeding habitat by Swift Parrots in the Maryborough-Dunolly region of central Victoria. The 900 km2 KBA includes several nature reserves, state parks and state forests, with only a few small blocks of private land. It excludes adjacent areas of woodland that are less suitable for Swift Parrots.

- Puckapunyal – Puckapunyal Military Area (PMA) is an Australian Army training facility and base 10 km west of Seymour, in central Victoria. The PMA contains box-ironbark forest that forms one of the largest discrete remnants of this threatened ecosystem in Victoria. The entire PMA, along with two small reserves and an army munitions storage site at nearby Mangalore, has been identified as a 435 km2 KBA because it supports the largest known population of Bush Stone-curlews in Victoria. It is also regularly visited by Critically Endangered Swift Parrots, often in large numbers.

- Rushworth Box-Ironbark Region – The Rushworth Box-Ironbark Region is a 510 km2 fragmented and irregularly shaped tract of land that encompasses all the box–ironbark forest and woodland remnants used as winter feeding habitat by Swift Parrots in the Rushworth-Heathcote region of central Victoria. It lies north of, and partly adjacent to, the Puckapunyal KBA. The site includes the Heathcote-Graytown National Park, several nature reserves and state forests, with a few small blocks of private land. It excludes other areas of woodland that are less suitable for the Swift Parrot. The region was identified as an KBA because, when the flowering conditions are suitable it supports up to about 70 Swift Parrots.

- St Arnaud Box-Ironbark Region – The St Arnaud Box-Ironbark Region is a 481 km2 fragmented and irregularly shaped tract of land that encompasses all the box-ironbark forest and woodland remnants used as winter feeding habitat by Swift Parrots in the St Arnaud-Stawell region of central Victoria. The site lies west of the Maryborough-Dunolly Box-Ironbark Region KBA. It includes the St Arnaud Range National Park, several nature reserves and state forests, with a few small blocks of private land. It excludes other areas of woodland that are less suitable for Swift Parrots. The region was identified as a KBA because, when flowering conditions are suitable it supports up to about 75 Swift Parrots.

- Warby-Chiltern Box-Ironbark Region – The Warby–Chiltern Box–Ironbark Region comprises a cluster of separate blocks of remnant box-ironbark forest habitat, with a collective area of 253 km2, in north eastern Victoria. This site lies to the east of the Rushworth Box-Ironbark Region KBA. It includes the Reef Hills and Warby-Ovens National Parks, Killawarra Forest, Chesney Hills, Mount Meg Reserves, Winton Wetlands Reserve, the Boweya Flora and Fauna Reserve, Rutherglen Conservation Reserve, Mount Lady Franklin Reserve and Chiltern-Mount Pilot National Park. Most of it lies within protected areas or state forests, encompassing only small blocks of private land. The site has been identified as an KBA because it provides feeding habitat for relatively large numbers of non-breeding Swift Parrots when flowering conditions are suitable, as well as the Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeaters.

Tasmania

- Bruny Island – Bruny Island is a 362 km2 island located off the south-eastern coast of Tasmania. Bruny Island is classified as a KBA because it supports the largest population of the Endangered Forty-spotted Pardalote, up to a third of the population of the Swift Parrot in a given year, subject to seasonal flowering conditions.

- Maria Island – Maria Island is a mountainous island located in the Tasman Sea, off the east coast of Tasmania. The 115 km2 island is contained within the Maria Island National Park, which includes a marine area of 18 km2 off the island's northwest coast. Maria Island has been identified as a KBA because it supports significant numbers of Endangered Forty-spotted Pardalotes, and, subject to seasonal flowering conditions, a significant number of Swift Parrots.

- South-east Tasmania – The South-east Tasmania KBA encompasses much of the land retaining forest and woodland habitats, suitable for breeding Swift Parrots and Forty-spotted Pardalotes, from Orford to Recherche Bay in south-eastern Tasmania. This large 335,777-hectare KBA comprises wet and dry eucalypt forests containing old growth Tasmanian Blue Gums or Black Gums, and grassy Manna Gum woodlands, as well as suburban residential centres and farmland where they retain large flowering, and adjacent hollow-bearing, trees. Key tracts of forest within the KBA include Wielangta, the Meehan and Wellington Ranges, and the Tasman Peninsula.

Habitat critical to the survival of a species or ecological community refers to areas that are necessary:

- For activities such as foraging, breeding, roosting, or dispersal;

- For the long-term maintenance of the species or ecological community (including the maintenance of species essential to the survival of the species or ecological community, such as pollinators);

- To maintain genetic diversity and long-term evolutionary development; or

- For the reintroduction of populations or recovery of the species or ecological community.

Such habitat may be, but is not limited to: habitat identified in a recovery plan for the species or ecological community as habitat critical for that species or ecological community; and/or habitat listed on the Register of Critical Habitat maintained by the Minister under the EPBC Act.

The Swift Parrot breeds mostly on the east and south-east coast of Tasmania during summer and migrates to mainland Australia in autumn. During winter the species disperses across forests and woodlands, foraging on nectar and lerps mainly in Victoria and New South Wales. Small numbers of Swift Parrots are also recorded in the Australian Capital Territory, south eastern South Australia and southern Queensland. Within these habitats, Swift Parrots preferentially forage in large, mature trees (Kennedy 2000; Kennedy and Overs 2001; Kennedy and Tzaros 2005) that provide more reliable foraging resources than younger trees (Wilson and Bennett 1999; Law et al. 2000). The migratory nature of the species means that they require a large network of resources both during and between annual cycles. Actions that directly and/or indirectly affect the species or their habitats could compromise recovery.

Noting the requirements of the species, habitat critical to the survival for the Swift Parrot includes:

Breeding and foraging habitat in Tasmania

- In different years the majority of the breeding population may be concentrated within a subset of the potential breeding range, according to spatially and temporally variable flowering patterns of preferred foraging species.

- Therefore, within areas where breeding is most likely to occur based on known breeding records, scientific literature and expert opinion, habitat critical to survival of Swift Parrots comprises both potential foraging habitat – which is native forest and woodland containing either Blue Gum (E. globulus) and/or Black Gum (E. ovata) as a dominant, subdominant or low density species, and potential nesting habitat – which is forests or woodlands containing hollow-bearing eucalypt trees within foraging range (~10 km) of potential foraging habitat that is old enough to flower.

Foraging habitat on the Australian mainland

- All preferred foraging species within known and likely foraging habitat on the mainland including Yellow Gum (E. leucoxylon); Red Ironbark (E. tricarpa); Mugga Ironbark (E. sideroxylon); Grey Box (E. macrocarpa); White Box (E. albens); Yellow Box (E. melliodora); Swamp Mahogany (E. robusta); Forest Red Gum (E. tereticornis); Blackbutt (E. pilularis); and Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata).

Key considerations in assessing environmental impacts

Habitat critical to the survival of the Swift Parrot occurs across a wide range of land tenures, including on freehold land, travelling stock routes and reserves, publicly owned forests and state reserves, and national parks. The global KBA partnership currently recognises 18 KBAs as important for Swift Parrot conservation and to support the long-term persistence of the species. It is essential that protection is provided to these areas and that enhancement and restoration measures target these productive sites.

Whenever possible, habitat critical to the survival of the Swift Parrot should not be destroyed. Actions that have indirect impacts on habitat critical to the survival should be minimised (i.e. noise and light pollution). Actions that compromise adult and juvenile survival should also be avoided, such as the introduction of new diseases, weeds or predators.

Actions that remove habitat critical to the survival would interfere with the recovery of Swift Parrots and reduce the area of occupancy of the species. In Tasmania, it is important to retain a mosaic of breeding habitat (i.e. nesting and foraging areas), particularly on Bruny and Maria Islands where Sugar Gliders are not present. Where habitat loss continues to occur within foraging habitats on the Australian mainland, it is important to retain trees ≥ 60 cm diameter at breast height (DBH) or greater, together with at least five trees per hectare from a mixture of other age classes (30 to 40 cm, 40 to 50 cm and 50 to 60 cm DBH) to ensure continuity of food resources over time. If removal of habitat critical to the survival cannot be avoided or mitigated then an offset should be provided.

Surveys

When considering habitat loss, alteration or degradation to habitat in any part of the Swift Parrot’s range, including in areas where the species ‘may occur’, surveys for occupancy at the appropriate times of the year and identifying preferred foraging species remain an important tool in refining understanding of the area’s relative importance for Swift Parrots.

In addition, it is also important to note that Swift Parrots opportunistically use areas depending on the occurrence of eucalypt flowering. As a result, the absence of Swift Parrots from a given location at a given time cannot be taken as evidence that that location is unsuitable habitat. Rather, if there are potential food plants present (that include resources such as lerps, not just flowers) then that site may be utilised by Swift Parrots if conditions become favourable. This opportunistic habitat use means survey data and historical records need to be considered when assessing the relative importance of a local area or region for Swift Parrots, in addition to the knowledge that variation in local conditions is a crucial predictor of Swift Parrot presence/absence and site utilisation (Webb et al. 2019).

The Swift Parrot’s area of occupancy has declined significantly since European settlement, as can be inferred from the extent of habitat loss. For example, 83 per cent of box-ironbark habitat (the principal wintering habitat of the Swift Parrot on the mainland) has been cleared in Victoria, and 70 per cent has been cleared in New South Wales (Siversten 1993; Robinson and Traill 1996; Environment Conservation Council 2001). White Box-Yellow Gum-Blakely's Red Gum woodland, another important habitat in New South Wales, has been reduced to less than 4 per cent of its pre-European extent on the south-western slopes and southern tablelands of New South Wales (Saunders 2003). In Tasmania there has also been significant historical loss and alteration of habitat within the primary breeding and foraging range, along the south-east coast. This has included the loss of approximately 70 per cent of grassy Tasmanian Blue Gum forest (Saunders and Tzaros 2011) and over 90 per cent of Black Gum – Brookers Gum forest (Department of Environment and Energy 2018).

The main threats in Tasmania to the survival of the Swift Parrot are the predation of nestlings and incubating females by the introduced Sugar Glider, ongoing loss or degradation of breeding and foraging habitat through a range of processes including, forestry operations, land clearing and wildfire. The main threats on the Australian mainland include habitat loss from land clearing for agriculture and urban development, and to a lesser extent forest harvesting. Other identified threats include competition for foraging and nesting resources, mortality from collisions with human-made objects and impacts from climate change.

2.2.2 Habitat loss and alteration

Forestry and land clearing

Loss of potential breeding habitat in Tasmania via clearance for conversion to agriculture, native forest logging and intensive native forest silviculture practices continues to reduce the amount of available Swift Parrot nesting and foraging habitat and it therefore remains a significant threat to the continued persistence of the species (Saunders et al. 2007, Saunders and Tzaros 2011, Webb et al. 2017, Webb et al. 2019).

There are no comprehensive estimates assessing loss of potential breeding habitat through forest harvesting or land clearing in recent years across the species breeding range. However one case study using the Southern Forests Swift Parrot Important Breeding Area (SPIBA) (one of 15 key breeding regions delineated for management purposes, Forest Practices Authority, 2010) estimated that forest harvesting between 1997 and 2016 had resulted in as much as 23 per cent of identified potential nesting habitat being lost in this time, noting that prior to 2007, this region was not recognised as supporting Swift Parrot breeding (Webb et al. 2019).

Much of the Swift Parrot potential breeding habitat in Tasmania is on private and public land that is subject to management arrangements under the Tasmanian Forest Management System.

The process of adaptive management and continuous improvement is built into the Tasmanian Forest Management System, and specific management arrangements for Swift Parrots have continued to evolve since 1996 to account for new knowledge (e.g. Forest Practices Authority 2010; Munks et al. 2004). However there remains an ongoing need for continual monitoring, evaluation and adaptive improvement in management approaches, particularly with regards to measures addressing habitat recruitment, the refinement of knowledge including in regards to nesting and foraging habitat requirements and their spatial and temporal availability.

Harvesting operations and land clearing of foraging habitat on the Australian mainland also remains a substantial threat. Impacts on Swift Parrot habitat in NSW have been so severe that only 5 to 30 per cent of the original vegetation now remains, such as for Grey Box and Grassy White Box woodland, and what is left is often degraded (Saunders and Russell 2016). With such extensive losses of habitat there is an increased risk that the remaining areas fail to produce the necessary food resources in one year. Before such extensive habitat losses occurred, the birds had a much greater chance of locating the food resources they needed each year (Saunders and Russell 2016).

The loss of mature box-ironbark woodlands of central Victoria and coastal forests of New South Wales, including Spotted Gum forests on the south coast, reduces the suitability of these habitats for this species by removing mature trees which are preferred by Swift Parrots. Larger trees typically provide more reliable, greater quantity and quality of food resources than younger trees (Wilson and Bennett 1999; Kennedy and Overs 2001; Kennedy and Tzaros 2005). However, the extent of forest loss over Swift Parrot foraging habitat on the mainland has not been quantified, and the impacts from urban and agricultural land clearing and commercial harvesting operations on the mainland remain uncertain.

Firewood collection – illegal and legal

Firewood collection is a threat to nesting and foraging habitat in Tasmania and to foraging habitat on mainland Australia. Trees targeted by firewood collectors are often those most valuable to the Swift Parrot, being large, mature forage trees or trees with suitable nesting hollows. Registered firewood suppliers operate in accordance with industry codes of practice or are formally regulated, which typically includes provisions to not collect from areas that might have an impact on threatened species. However, there is a large, but unquantified unregulated and illegal harvest of firewood in Tasmania, and these collectors are impacting on Swift Parrot habitat. In some areas the local impacts of illegal firewood harvesting can be severe. For example, approximately one third of known nest trees have been illegally felled for firewood at one breeding site (Stojanovic, D., unpublished data).

Fire

Increases in fire frequency, intensity and scale pose a significant threat to avian communities. Where fire intervals are too short, flowering events and maturation of nectar-rich plant species may be reduced, resulting in a reduction of foraging resources for nectarivorous birds (Woinarski and Recher 1997). This is of particular concern in coastal New South Wales and in central Victoria where there is increasing residential and industrial development in close proximity to Swift Parrot habitat. Such developments are required to comply with new fire safety regulations involving clearing trees within fire protection zones and undertaking hazard reduction burns. With an increase in the human population residing adjacent to Swift Parrot habitat and increased accessibility to bushland areas, an increase in the incidence of accidental and deliberate fires will incrementally impact on Swift Parrot values across its range.

Fires may kill canopy trees but these (and hollows) may persist as dead stags. Fires may also lead to hollow formation (or a change in dimensions of existing hollows) in surviving trees or destroy hollow-bearing trees. Frequent fire may alter natural wildfire tree recruitment processes and hence dictate future availability of hollows (Woinarski and Recher 1997). Fires may also cause the collapse of hollow bearing trees, thus reducing hollow availability into the future. One long-term study looked at survival of nest trees over time and found that unburnt trees mostly survived but that nearly half of the trees burnt with cavities collapsed within six months of burning (Stojanovic et al. 2015). Further, hollow loss in the aftermath of fire may act to limit the short term abundance of nest sites in burned habitats. Stojanovic et al (2015 ) showed that of 63 per cent of known nest hollows that were burnt in a wildfire collapsed, reducing the availability of nests in an important breeding site.

In 2013 and 2019, fires in Tasmania impacted large areas of remaining breeding habitat. While difficult to accurately quantify the combined impact has been immense relative to the area of remaining breeding habitat and replacement time. In 2019–20, following years of drought (DPI 2020), catastrophic wildfire conditions culminated in fires that covered an unusually large area of eastern and southern Australia. The bushfires will not have impacted all areas equally: some areas burnt at very high intensity whilst other areas burnt at lower intensity, potentially even leaving patches unburnt within the fire footprint. However, an initial analysis estimates that between 10 and 30 per cent of the distribution range of the Swift Parrot was impacted to some degree. This type of event is increasingly likely to reoccur as a result of climate change.

Residential and industrial development

Urban, rural residential and industrial developments can pose a threat to habitat throughout the range of the species, with important breeding areas in Tasmania and key foraging areas in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland being of particular concern. Where potential breeding habitat is retained adjacent to developments there is an increased likelihood that potential nest trees could be removed for ‘human safety reasons’, including as part of establishing and maintaining fire breaks.

In central Victoria, urban and rural residential developments are increasingly encroaching into box-ironbark habitats, such as those around Bendigo. In New South Wales, urban and industrial expansion, particularly on the central and north coast pose an ongoing threat to winter foraging regions. In Queensland, urban development is of particular concern to the Swift Parrot at the northern extent of their winter range. In particular, the Gold Coast, Toowoomba and the Greater Brisbane region are at risk from tree removal associated with residential and industrial development.

Agricultural tree senescence and dieback

Much of the habitat used by Swift Parrots in agricultural landscapes are forest remnants or isolated, scattered paddock trees. This habitat continues to be lost through senescence, dieback, over grazing and through ongoing removal of paddock trees to enhance farm productivity. This is of particular concern in eastern Tasmania, Victoria and throughout New South Wales.

2.2.3 Predation by Sugar Gliders

Predation on the nest by Sugar Gliders on the mainland of Tasmania is a significant threat to the species (Stojanovic et al 2014). Sugar Gliders eat Swift Parrot eggs, nestlings and females, and impose a severe, sex-biased demographic pressure on the population (Stojanovic et al. 2014; Heinsohn et al. 2015, Heinsohn et al. 2019). Stojanovic et al. (2014) showed that survival of Swift Parrot nests was a function of modelled mature forest cover in the surrounding landscape and the likelihood of Sugar Glider predation decreased with increasing forest cover.

While a species native to the Australian mainland, Sugar Gliders were likely introduced to mainland Tasmania around 1835 (Campbell et al. 2018). The Tasmanian Government subsequently amended Schedule 2 of the Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulations 2021 to remove Sugar Gliders in 2018. Maria and Bruny Islands are free of Sugar Gliders and it is important to remain vigilant to possible incursions. Maintaining the Sugar Glider-free status of these two islands is critical for the conservation of Swift Parrots in Tasmania.

Control of the impacts of Sugar Gliders on Swift Parrots has proven very challenging. Although automated doors fitted to nest boxes are effective at protecting individual nests from predation (Stojanovic et al. 2019), there remains major uncertainty about how to protect nests in tree hollows. An attempt to use fear-based approaches to reduce predation impacts was ineffective (Owens et al. 2020). Early attempts to control Sugar Gliders by culling them have proven unsuccessful to date (Stojanovic et al. in review) although further efforts are underway to evaluate different techniques. Nevertheless, the weight of evidence suggests that if controlling Sugar Glider predation on Swift Parrots is possible, deploying these approaches at large enough scales to benefit the population as a whole is an ambitious aspiration. This challenge is made harder because Sugar Gliders are widespread in Swift Parrot nesting habitat (Allen et al. 2018) and tolerate landscapes with a high degree of forest disturbance.

2.2.4 Collision mortality

Collisions with wire netting, mesh fences, windows and cars cause mortality to Swift Parrots in urban areas throughout the species’ range (Pfennigwerth 2008; Hingston 2019) in Tasmania and mainland eastern Australia. Continuing urban encroachment into breeding and foraging habitat is likely to exacerbate this problem. Swift Parrots are sometimes found injured or dead from collisions during the breeding season, with few birds released back into the wild. The threat is exacerbated in years when foraging resources are concentrated in or near to urban areas.

The construction of wind energy turbines and associated energy infrastructure (i.e. powerlines) in south-eastern Australia may also have implications for the conservation of the Swift Parrot where infrastructure is poorly situated (Barrios and Rodriguez 2004). Parrots may be killed through collision, or their behaviour may be modified by the presence of these structures leading to avoidance of suitable habitat. The potential impacts of these structures may be greatest where they are situated along migration routes where a large proportion of the population may be exposed to the threat. Wind turbines and associated energy infrastructure are located, and continue to be built, along the migratory route and within the non-breeding range. This ongoing development increases the likelihood of the birds being exposed to collision mortality or loss of habitat.

2.2.5 Competition

Swift Parrots can experience increased competition for resources from a range of native and non-native species, including the aggressive Noisy Miners (Manorina melanocephala) and introduced Rainbow Lorikeets (Trichoglossus haematodus) within altered habitats (Ford et al. 1993; Grey et al. 1998; Hingston 2019), and from introduced birds and bees (Brown 1989; Paton 1993; Hingston et al. 2004; Heinsohn et al. 2015; Hingston and Wotherspoon 2017; Hingston 2019). Swift Parrots compete with European Honeybees (Apis mellifera) and Starlings for tree cavities, where nestling parrots can be killed and the cavities usurped (Heinsohn et al. 2015). This competition is most prevalent in forest that is disturbed or fragmented (Stojanovic, D. unpublished data).

2.2.6 Climate variability and change

Drought is a natural part of Australia’s climate and the present-day existence of the Swift Parrot demonstrates that the species is well-adapted to cope with a dry climate. However, the relatively recent and rapid decrease in available habitat, coupled with prolonged or more frequent drought periods, could increase threats on an already depleted population.

Climate projections for eastern Australia include reduced rainfall, increased average temperatures, and more frequent droughts and fires (CSIRO 2007; CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology 2015). Climate change impacts are compounded by the Swift Parrot’s restricted area of occupancy, low (and decreasing) population, low population density at sites and short generation length (under 10 years). These variables are identified as increasing the risk of local extinction (Pearson et al. 2014) and are amongst the strongest predictor of species’ vulnerability to climate change (Pearson et al. 2014).

Loss of nesting and foraging habitat from climate change and changes in seasonality and the geographic pattern of flowering is likely to pose a significant threat to the Swift Parrot (Porfirio et al. 2016). Direct impacts to the Swift Parrot as a result of climate change include cases of climate-related nest failures, altered rainfall patterns, flowering failures on the mainland, and extreme wildfires.

Climate change management requires both domestic and international action to stop further emission of anthropogenic greenhouse gases. Although management of this global issue is beyond the scope of this plan, long-term monitoring of the species and habitats may be needed to understand the sensitivities of the Swift Parrot to climate change and to form the basis for future adaptive conservation management strategies. Further, the cumulative effects of other threats together with climate change need to be considered for effective and adaptive long-term management of the Swift Parrot.

2.2.7 Illegal wildlife capture and trading

Unregulated trade in wildlife has become a major factor in the decline of many species of animals and plants. Therefore the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was established and is enforceable under the EPBC Act (Department of Environment and Heritage 2005b). The Swift Parrot may be susceptible to illegal wildlife capture and trading activities.

2.2.8 Cumulative impacts

Each of the identified threats to the Swift Parrot has the potential to compromise the long-term survival of the species, and where more than one threat is present the cumulative effect is likely to be substantially greater than the sum of the individual threats. In addition, impacts from a single threat increases the overall risk of extinction, such as repeated small-scale clearing for developments that do not meet significant impact thresholds, but whose total impact over time contributes to the species decline.

Genetic analysis confirms that Swift Parrots form a single, genetically mixed (panmictic), breeding population (Stojanovic et al. 2018). Therefore, the actions described in this recovery plan are designed to provide ongoing protection for all Swift Parrots throughout their range.

Long-term vision

The Swift Parrot population has increased in size to such an extent that the species no longer qualifies for listing as threatened under any of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 listing criteria.

Recovery plan objectives

- By 2032, maintain or improve the extent, condition and connectivity of habitat of the Swift Parrot.

- By 2032, anthropogenic threats to Swift Parrot are demonstrably reduced.

- By 2032, measure and sustain a positive population trend.

This will be achieved by implementing the actions set out in this Recovery Plan that minimise threats including protecting and enhancing the species’ habitat throughout its range, adequately monitoring the species, generating new knowledge to guide recovery and increasing public awareness.

Strategies to achieve objective

- Maintain known Swift Parrot breeding and foraging habitat at the local, regional and landscape scales.

- Reduce impacts from Sugar Gliders at Swift Parrot breeding sites.

- Monitor and manage other sources of mortality.

- Develop and apply techniques to measure changes in population trajectory in order to measure the success of recovery actions.

- Improve understanding of foraging and breeding habitat use at a landscape scale in order to better target protection and restoration measures.

- Engage community and stakeholders in Swift Parrot conservation.

- Coordinate, review and report on recovery progress.

To ensure the conservation of Swift Parrots there is an urgent need to protect existing breeding and foraging habitat across a diversity of tenure in south-eastern Australia; to reduce the impact of Sugar Glider predation; to better understand and manage all trophic levels of climate change impacts and to substantially increase habitat restoration efforts throughout the species’ range (Saunders and Russell 2016). Without strong direct action at all levels, from local landholders through to state and national government agencies responsible for managing this species and its habitat, the future of this species is not secure (Saunders and Russell 2016).

Actions identified for the recovery of Swift Parrot are described as part of the strategies outlined in this chapter. It should be noted that some of the objectives are long-term and may not be achieved prior to the scheduled five-year review of the recovery plan. Priorities are assigned to each action according to these definitions:

- Priority One – taking prompt action is necessary in order to mitigate the key threats to Swift Parrot and also provide valuable information to help identify long-term population trends.

- Priority Two – action would provide a more informed basis for the long-term management and recovery of Swift Parrot.

- Priority Three – action is desirable, but not critical to the recovery of Swift Parrot or assessment of trends in that recovery.

Strategy 1 Maintain known Swift Parrot breeding and foraging habitat at the local, regional and landscape scales

Action | Description | Priority | Performance criteria | Responsible agencies and potential partners 1 | Indicative cost |

1.1 | Identify breeding and foraging habitat for Swift Parrot | 1 | - Existing and new information has been reviewed and used to identify important breeding and foraging habitat that requires management intervention

- Important habitat has been prioritised to determine which sites require increased protection based on its importance and the risks to its persistence

- Important habitat has been accurately mapped and is available to all relevant stakeholders and land managers

- New knowledge has been incorporated into relevant policy documents to support management interventions

- Key Biodiversity Areas have been reviewed and updated as new information becomes available

| Australian Government State governments Recovery Team Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions BirdLife Australia | $125,000 pa |

1.2 | Review and revise as appropriate Swift Parrot management priorities, recommendations, planning tools and procedures as new information becomes available | 2 | - New information on breeding and foraging locations is incorporated into the existing regulations, codes of practice, management recommendations, and planning tools and procedures to better manage the Swift Parrot population across its range

| Australian Government State governments Local government | Core government business |

1.3 | Protect areas of ‘habitat critical to survival’ not managed under an RFA agreement from developments (e.g. from residential developments, mining activity, wind and solar farms) and land clearing for agriculture through local, state and Commonwealth Government mechanisms | 1 | - Developments have avoided areas of ‘habitat critical to survival’ for the Swift Parrot where possible

- Where avoidance is not possible, the extent and severity of clearing of mature foraging and nesting trees in areas of ‘habitat critical to the survival’ of the Swift Parrot has been measurably minimised and offset

- Any developments in areas of ‘habitat critical to survival’ have incorporated suitable threat mitigation measures

- If avoidance or mitigation has been found to be impossible, any developments that proceeded in areas of ‘habitat critical to survival’ have provided offsets compliant with the approved offset regulations and calculators and provided measurable benefits to the Swift Parrot population in line with strategies outlined in this recovery plan

| Australian Government State governments Local government | Core government business |

1.4 | Enhance the quality and extent of existing breeding habitat in Tasmania through strategic plantings | 2 | - Manage regenerating and regrowth Blue Gum and Black Gum forest to provide foraging habitat into the future

- Encourage large-scale plantings of Blue Gum and Black Gum forest and woodland by landholders and land managers in priority areas through a strategic landscape approach

| Australian Government State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders BirdLife Australia NGOs | $250,000 pa |

1.5 | Reduce firewood collecting in breeding, foraging and non-breeding habitat | 2 | - Quantify the extent of firewood harvesting in breeding, foraging and non-breeding habitat

- Compliance and enforcement activities have been targeted at reducing illegal firewood harvesters

- A voluntary code of practice for the firewood industry (including a certification system) has been developed and introduced to enable adequate knowledge of and regulation of impacts on Swift Parrot habitat

| State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders | $75,000 pa |

1.6 | Develop agreements between local government and government agencies that aim to maintain and enhance Swift Parrot habitat | 2 | - Management agreements have been developed between local government and state government agencies which maintain and enhance Swift Parrot habitat

- Reporting mechanisms have been developed to capture the outcomes of land use decisions and planning involving Swift Parrot habitat

| State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders | $150,000 pa |

1.7 | Manage important winter foraging habitat and provide adequate on-going conservation management resources where appropriate | 1 | - Management plans for important winter foraging habitat/sites have been developed and implemented

- Management plans have been adequately resourced

- Consideration has been given to enhance formal protection for sites where appropriate (i.e. through new conservation reserves, national parks etc.)

| State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders | $350,000 pa |

1.8 | Identify and protect remnants of state and Commonwealth owned land in areas of ‘habitat critical for survival’ for Swift Parrots | 3 | - Unprotected state and Commonwealth owned remnants in areas of ‘habitat critical to survival’ for Swift Parrots have been identified

- Remnants have been ranked for their conservation significance and mapped

- Consideration has been given to enhance formal protection for sites where appropriate (i.e. through new conservation reserves, national parks etc)

- Local management plans have been developed for priority remnants to maximise conservation values of the identified sites

| Australian Government State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders BirdLife Australia NGOs | $150,000 pa |

1.9 | Incorporate Swift Parrot conservation priorities into covenanting and other private land conservation programs. | 3 | - Key breeding and foraging sites on private land identified and habitat quality assessed

- Identified sites protected through covenanting and other private land conservation programs

| Australian Government State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders BirdLife Australia NGOs | $250,000 pa |

1 Lead organisations are identified in bold type.

Strategy 2 Reduce impacts from Sugar Gliders at Swift Parrot breeding sites

Action | Description | Priority | Performance criteria | Responsible agencies and potential partners 1 | Indicative cost |

2.1 | Determine Sugar Glider density across Swift Parrot breeding areas and devise a management strategy for Sugar Gliders | 1 | - Knowledge of Sugar Glider densities in Swift Parrot breeding areas has improved

- Sugar Glider density across Swift Parrot breeding areas has been mapped

- A management strategy has been developed to manage Sugar Glider population at important sites, such as breeding areas regularly used by Swift Parrots

- The strategy includes actions that address increased use of nest protection methods and/or programs that reduce Sugar Glider numbers

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $125,000 pa |

2.2 | Test mechanisms to restrict Sugar Gliders from Swift Parrot nest hollows | 1 | - Sugar Glider exclusion trials have been undertaken in key Swift Parrot breeding areas

- A range of different exclusion methods have been assessed for their effectiveness

- New knowledge has been incorporated into management interventions

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $100,000 pa |

2.3 | Trial methods to reduce Sugar Glider density from key breeding areas | 1 | - Trials have been undertaken to test the impacts of predator playbacks on Sugar Glider density, Swift Parrot mortality and breeding success

- Trials have been undertaken to test the impacts of directly reducing Sugar Glider density (through trapping and euthanising) on Swift Parrot mortality and breeding success

- New knowledge has been incorporated into management interventions

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $50,000 pa |

2.4 | Better understand extinction/colonisation dynamics of Sugar Gliders | 1 | - An improved understanding can be demonstrated of the re-colonisation dynamics of Sugar Gliders resulting from local management interventions and population reductions

- An improved understanding can be demonstrated of the breeding and foraging ecology of Sugar Gliders in south-east Tasmania

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $50,000 |

2.5 | Further investigate the possible link between forest condition, Sugar Glider density and Swift Parrot predation rates | 1 | - An improved understanding can be demonstrated of the link between forest cover, patch size, Sugar Glider density and Swift Parrot predation rates and breeding success

- New knowledge has been incorporated into management interventions

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $125,000 pa |

2.6 | Develop communication strategy specific to Sugar Glider management | 1 | - A targeted communications strategy has been developed that communicates why Sugar Glider numbers need to be controlled within Swift Parrot breeding areas

- Communication outputs have included but not limited to, social media networks, pamphlets and community presentations

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $30,000 |

2.7 | Ensure mechanisms are in place for the early detection, and control, of Sugar Gliders introduced to Maria and Bruny Islands | 1 | - A process has been developed and implemented to ensure the early detection of Sugar Gliders on islands where Swift Parrots breed but which are currently Sugar Glider free

- A management plan and control program that addresses the prevention of Sugar Glider invasion and spread and management of impacts across Tasmania is developed and approved by 2023

- The management plan has included rapid response protocols to eliminate Sugar Gliders on Maria and Bruny Islands

| Tasmanian Government NRM regional bodies Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $75,000 pa |

2.8 | Continue regulatory reform of Sugar Glider protected wildlife status | 1 | - The Tasmanian Government has given consideration to declaring Sugar Gliders as vermin under the Vermin Control Act 2000 (Tas) or as an invasive species under subsequent Tasmanian legislation should the Vermin Control Act be replaced

| Tasmanian Government | Core government business |

1 Lead organisations are identified in bold type.

Strategy 3 Monitor and manage other sources of mortality

Action | Description | Priority | Performance criteria | Responsible agencies and potential partners 1 | Indicative cost |

3.1 | Continue to raise public awareness of the risks of collisions and how these can be minimised | 2 | - Existing collision impact guidelines have been updated as required and made accessible to relevant stakeholders

- There has been a demonstrated decrease in the number of collisions

| Australian Government State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders BirdLife Australia NGOs | $50,000 |

3.2 | Conduct a national sensitivity analysis on the potential impact of terrestrial and offshore windfarm installations | 2 | - A comprehensive national sensitivity analysis has been published identifying the risks of collision and displacement of Swift Parrots

- New information has been used to update state and local planning guidelines

| Research agencies NGOs Academic institutions | $125,000 |

3.3 | Monitor for outbreaks of disease (e.g. of Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease), that may impact on the viability of the wild population | 3 | - The incidence of disease has been recorded during handling and monitoring of Swift Parrots

- A management strategy has been developed if incidence of disease is noted to be increasing

| Australian Government State governments Local government NRM regional bodies Private landholders BirdLife Australia NGOs | $50,000 |