Australian War Memorial, Campbell and Mitchell, ACT

Indigenous Cultural Heritage Assessment

March 2008

Navin Officer

heritage consultants Pty Ltd

acn: 092 901 605

Number 4

Kingston Warehouse 71 Leichhardt St.

Kingston ACT 2604

Australian War Memorial, Campbell and Mitchell, ACT

Indigenous Cultural Heritage Assessment

March 2008

Navin Officer

heritage consultants Pty Ltd

acn: 092 901 605

Number 4

Kingston Warehouse 71 Leichhardt St.

Kingston ACT 2604

A Report to Godden Mackay Logan (GML) for the Australian War Memorial

ph 02 6282 9415

fx 02 6282 9416

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Identify Aboriginal heritage within the study areas;

Assess the significance of Aboriginal heritage sites within the study areas;

Identify those sites that warrant permanent conservation and are a permanent constraint to disturbance within the study areas;

Identify areas where further information is required to make an assessment on the heritage value of a site; and

Provide management recommendations to achieve protection for those sites that warrant it.

No Aboriginal sites have been previously identified within the study areas;

No Aboriginal sites or areas of archaeological potential/sensitivity were identified in the Australian War Memorial Mitchell Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation. There are no indigenous heritage assets or constraints relating to the Australian War Memorial Mitchell Precinct; and

One Aboriginal site, isolated find, AWM1, was identified in the Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation. The site has low archaeological values, but is valued by the local Aboriginal community and as such it meets Criterion (i) of the Commonwealth Heritage Listing criteria.

Site AWM1 be listed on the Australian War Memorial Heritage Register and ACT Heritage Register; and

Impact to site AWM1 should be avoided, if disturbance is anticipated potential activities around the periphery of the site should be managed and the site fenced where appropriate to demarcate site boundary and to control access.

~ o0o ~

TABLE OF CONTENTS

APPENDIX 1 ABORIGINAL PARTICIPATION FORM................................24

The Australian War Memorial (AWM) is currently developing the Australian War Memorial Heritage Register in conjunction with Australian War Memorial’s existing collection management database (MICA). The Register is a list of places and place elements which have been identified as having Commonwealth Heritage value.

Godden Mackay Logan (GML) has been engaged by the Australian War Memorial to undertake a cultural heritage assessment of the Australian War Memorial’s two precincts at Campbell and Mitchell, for the heritage identification and assessment program of the AWM Commonwealth Heritage Register.

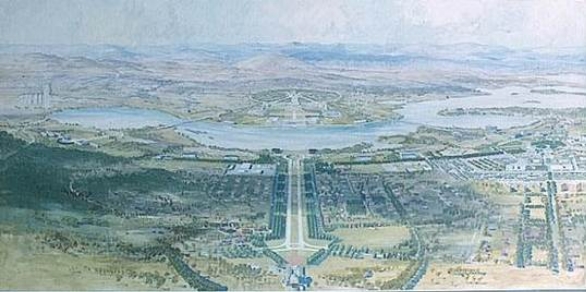

The Campbell site is situated east of the city and lies at the foot of Mount Ainslie, including the National Memorial and Grounds. The Campbell precinct is bound by Limestone Avenue, Fairbairn Avenue and Treloar Crescent, Campbell (Figure 1.1).

The Mitchell precinct is located in North Canberra and consists of three buildings including Annex A - Mitchell Conservation and Repository, Treloar B and Treloar C (Figure 1.2).The Mitchell property is situated on both sides of Vicars Street and is further bound by Lysaght and Callan Streets.

This report collates and documents the results of the indigenous cultural heritage assessment conducted for the Australian War Memorial Campbell and Mitchell sites. The assessment included consultation with ACT Aboriginal community organisations, database and literature review and field survey of the subject areas. The report will assist with the Australian War Memorial’s assessment for the development of the Commonwealth Heritage Register regarding indigenous heritage values.

The report was commissioned by Godden Mackay Logan.

1.1 Report Outline

This report:

Figure 1.1 Location of the Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct study area (solid blue outline) (Extract from Hall 1:25,000 topo map 2nd edition L&PI 2003)

Figure 1.2 Location of the Australian War Memorial Mitchell Precinct study area (shaded in dark blue) (Extract from Hall 1:25,000 topo map 2nd edition L&PI 2003)

2. ABORIGINAL PARTICIPATION

2. ABORIGINAL PARTICIPATION

Four Registered Aboriginal Organisations (RAOs) have an interest in cultural heritage issues in the ACT and are registered with the ACT Heritage Unit. They are the:

Contact was made with each group to inform them of the project and to organise representation during the field survey. Subsequently, Justin Williams from the CBAC, Don Bell from Buru Ngunnawal and Graeme Riley from Ngarigu, attended the program at the Campbell Precinct.

Justin Williams (CBAC) and Don Bell (Buru Ngunnawal) were in attendance during the survey of the Mitchell Precinct, the team was accompanied by Craig Seaton from the Australian War Memorial.

A copy of this draft report will be forwarded to the participating RAOs for review and comment prior to finalisation.

Records of Aboriginal Participation for the field survey component of this project are provided in Appendix 1.

3. STUDY METHODOLOGY

3. STUDY METHODOLOGY

3.1 Literature and Database Review

A range of documentation was reviewed in assessing archaeological knowledge for the Campbell and Mitchell study areas and surrounds. This literature and data review was used to determine if known Aboriginal sites were located within the area under investigation, to facilitate site prediction on the basis of known regional and local site patterns, and to place the area within an archaeological and heritage management context.

Aboriginal literature sources included the Heritage Online database (HERO) maintained by the ACT Heritage Unit, and associated files and catalogue of archaeological reports.

Searches were undertaken of the following heritage registers and schedules:

Fieldwork was conducted over one day in February 2008. Field survey was conducted on foot and involved inspection of all areas of ground surface visibility within the Campbell and Mitchell study areas.

3.3 Project Personnel

Field survey was undertaken by archaeologists Rebecca Yit and Nicola Hayes. Sites Officers Mr Don Bell (Buru Ngunawal), Grahame Riley (Ngarigu) and Justin Williams (CBAC) were also in attendance. Craig Seaton (AWM) provided assistance at the AWM Campbell Precinct.

This report was prepared by Rebecca Yit.

3.4 Recording Parameters

The archaeological survey aimed at identifying material evidence of Aboriginal occupation as revealed by surface artefacts and areas of archaeological potential unassociated with surface artefacts. Potential recordings fall into three categories: isolated finds, sites and potential archaeological deposits.

Isolated finds

An isolated find is a single stone artefact, not located within a rock shelter, and which occurs without any associated evidence of Aboriginal occupation within a radius of 60 metres. Isolated finds may be indicative of:

Except in the case of the latter, isolated finds are considered to be constituent components of the

Except in the case of the latter, isolated finds are considered to be constituent components of the

background scatter present within any particular landform.

The distance used to define an isolated artefact varies according to the survey objectives, the incidence of ground surface exposure, the extent of ground surface disturbance, and estimates of background scatter or background discard densities. In the absence of baseline information relating to background scatter densities, the defining distance for an isolated find must be based on methodological and visibility considerations. Given the varied incidence of ground surface exposure and deposit disturbance within the study area, and the lack of background baseline data, the specification of 60 metres is considered to be an effective parameter for surface survey methodologies. This distance provides a balance between detecting fine scale patterns of Aboriginal occupation and avoiding environmental biases caused by ground disturbance or high ground surface exposure rates. The 60 metre parameter has provided an effective separation of low density artefact occurrences in similar southeast Australian topographies outside of semi-arid landscapes.

Background scatter

Background scatter is a term used generally by archaeologists to refer to artefacts which cannot be usefully related to a place or focus of past activity (except for the net accumulation of single artefact losses).

However, there is no single concept for background discard or 'scatter', and therefore no agreed definition. The definitions in current use are based on the postulated nature of prehistoric activity, and often they are phrased in general terms and do not include quantitative criteria. Commonly agreed is that background discard occurs in the absence of 'focused' activity involving the production or discard of stone artefacts in a particular location. An example of unfocused activity is occasional isolated discard of artefacts during travel along a route or pathway. Examples of 'focused activity' are camping, knapping and heat-treating stone, cooking in a hearth, and processing food with stone tools. In practical terms, over a period of thousands of years an accumulation of 'unfocused' discard may result in an archaeological concentration that may be identified as a 'site'. Definitions of background discard comprising only qualitative criteria do not specify the numbers (numerical flux) or 'density' of artefacts required to discriminate site areas from background discard.

Sites

A site is defined as any material evidence of past Aboriginal activity that remains within a context or place which can be reliably related to that activity.

Frequently encountered site types within southeastern Australia include open artefact scatters, coastal and freshwater middens, rock shelter sites including occupation deposit and/or rock art, grinding groove sites and scarred trees. For the purposes of this section, only the methodologies used in the identification of these site types are outlined.

Most Aboriginal sites are identified by the presence of three main categories of artefacts: stone or shell artefacts situated on or in a sedimentary matrix, marks located on or in rock surfaces, and scars on trees. Artefacts situated within, or on, a sedimentary matrix in an open context are classed as a site when two or more occur no more than 60 metres away from any other constituent artefact. The 60 metre specification relates back to the definition of an isolated find (Refer above).

Any location containing one or more marks of Aboriginal origin on rock surfaces is classed as a site. Marks typically consist of grinding features such as grinding grooves for hatchet heads, and rock art such as engravings, drawings or paintings. The boundaries of these sites are defined according to the spatial extent of the marks, or the extent of the overhang, depending on which is most applicable to the spatial and temporal integrity of the site.

4. ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

4. ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

The Australian War Memorial study area comprises two precincts, situated at Campbell and Mitchell in northern ACT.

4.1 Campbell Precinct

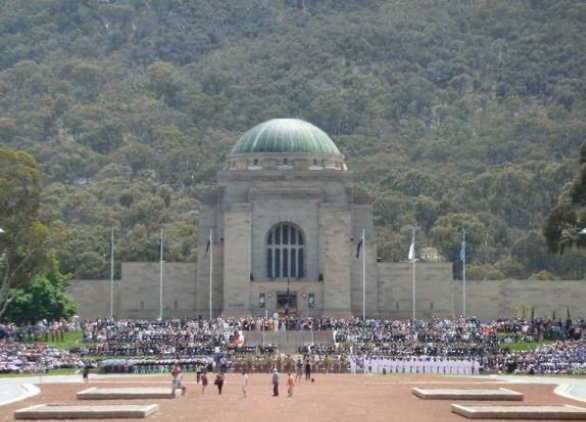

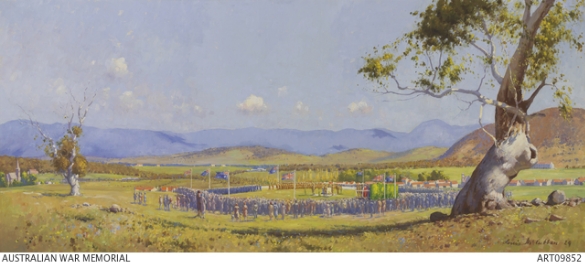

The Campbell precinct study area consists of the National Memorial and Grounds and comprises an area of approximately of 14 hectares. The Campbell study area is contained by the major arterial roads of Limestone Avenue to the southwest and Fairbairn Avenue to the south. Treloar Crescent encloses the northern and eastern boundaries of the study area. The site houses four buildings including the Australian War Memorial, the CEW Bean Building, the Administration Building and the Outpost Café. The grounds of the precinct have been extensively landscaped to contain memorials, plaques, a parade garden and commemorative and landscape plantings (Figure 4.1).

The study area consists predominantly of the lower southwest facing basal slopes of the Mount Ainslie and Mount Pleasant ridgeline water catchment. An unnamed tributary draining into Lake Burley Griffin is located along the eastern boundary of the study area.

The bedrock geology of the Campbell precinct is dominated by the Ainslie volcanics which consists of Devonian rocks including rhyolite, dacite, tuff, and quartz porphyry (Canberra 1:250,000 geological map 2nd Ed 1964). Soils within the area typically include red earths and red and yellow podzolic soils. Massive earths of a red or brown colour occur on the fan deposits flanking Mount Ainslie (Walker 1978).

The Campbell study area is characterised by a constructed undulating landscape where extensive landscaping and modification has subsumed the original landscape topography. Vegetation at the Campbell site represents contemporary plantings since the 1940s (pers. comm. Craig Seaton, AWM). Plantings of eucalypts and wattles have been developed on the eastern portion of the study area, appearing as an extension of the Mount Ainslie vegetation (Figure 4.2). Exotic species of deciduous and coniferous trees (Figure 4.3) have been developed on the western portion of the site (Australian Heritage List #105889 Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade, Anzac Pde, Campbell, ACT).

Extensive landuse impacts and modification to the Campbell site has resulted in widespread disturbance of the upper soil layers within the study area. The types of landscape disturbance which are evident within the study area include:

Changes in vegetation cover will have had considerable impact on the upper soil profile throughout the study area. The removal of native vegetation would have prompted erosion and surface instability on the valley slopes and the sedimentation of the valley floor.

This land use history will have significantly impacted the survival and integrity of the prehistoric archaeological record. It is probable that any possible surface scatters of artefacts which occur within the uppermost soil layers will have undergone varying degrees of horizontal and vertical disturbance particularly from the removal of vegetation and extensive plantings. However, unless impact has been wholesale, (such as in excavation, filling or recontouring) it is frequently possible to identify a remnant scatter of disturbed artefacts which mark such sites.

Figure 4.1 Drawing of Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct (plan supplied by AWM)

Figure 4.2 View northwest towards plantings of native trees in the eastern portion of the Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct

Figure 4.3 View of western portion of Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct looking west towards landscaped grounds and plantings of exotic tree species

4.2 Mitchell Precinct

The Mitchell precinct consists of three conservation and storage buildings situated on the east and western side of Vicars Street, Mitchell. The buildings include Treloar A (Annexe A-Mitchell Conservation and Repository), Treloar B and Treloar C.

The Mitchell study area has undergone extensive landscape modification and some 90% of the ground surface is obscured by structures which have been constructed almost to the limits of the property.. A narrow margin of land to the east of Treloar A represents the only exposed ground surface within the Mitchell precinct study area. This area has been extensively disturbed by construction activities. In addition, the majority of the ground surface has been covered with concrete, bitumen or paved. Figures 4.4 and 4.5 provide views of the ground surface exposure east of Treloar A.

The bedrock geology consists of Lower Silurian mudstone, siltstone and minor shale and chert belonging to the Canberra Formation typical of the geology of the north Canberra area. The rock

base is bedded almost vertically and consists predominantly of platey, soft, weathered shales. Narrow protruding outcrops of more resistant bedrock occur throughout the non-alluvial topography of the area. These are mostly discontinuous or locally isolated outcrops consisting predominantly of shales and variously graded and fractured chert.

base is bedded almost vertically and consists predominantly of platey, soft, weathered shales. Narrow protruding outcrops of more resistant bedrock occur throughout the non-alluvial topography of the area. These are mostly discontinuous or locally isolated outcrops consisting predominantly of shales and variously graded and fractured chert.

Vegetation within the Mitchell precinct consists of very sparse remnant native woodland trees, to natural Eucalypt woodland in varying states of regeneration and understorey density. Sullivans Creek, which runs adjacent to the western boundary of the Mitchell Precinct, has been extensively modified and channelised. This is likely to have caused major disturbance to any archaeological deposits occurring along the original creekline.

Similar to the Campbell site, the land use history of the Mitchell precinct will have significantly impacted the survival and integrity of the prehistoric archaeological record. It is probable that any archaeological deposits occurring within this location have been extensively disturbed, covered, and/or destroyed.

Figure 4.4 View of ground surface exposure looking east, Australian War Memorial Treloar A, Mitchell Precinct

Figure 4.5 View looking west from eastern boundary of Australian War Memorial Treloar A, across visible ground surface, Mitchell Precinct

5. ABORIGINAL CONTEXT

5. ABORIGINAL CONTEXT

5.1 Tribal Boundaries and Ethnohistory

Tribal boundaries within Australia are based largely on linguistic evidence and it is probable that boundaries, clan estates and band ranges were fluid and varied over time. Consequently 'tribal boundaries' as delineated today must be regarded as approximations only, and relative to the period of, or immediately before, European contact. Social interaction across these language boundaries appears to have been a common occurrence.

According to Tindale (1940) the territories of the Ngunawal, Ngarigo and the Walgalu peoples coincide and meet in the Queanbeyan area. The Fairbairn Avenue study area probably falls within the tribal boundaries of the Ngunnawal people.

References to the traditional Aboriginal inhabitants of the Canberra region are rare and often difficult to interpret (Flood 1980). The consistent impression however is one of rapid depopulation and a desperate disintegration of a traditional way of life over little more than fifty years from initial white contact (Officer 1989). The disappearance of the Aborigines from the tablelands was probably accelerated by the impact of European diseases which may have included the smallpox epidemic in 1830, influenza, and a severe measles epidemic by the 1860's (Flood 1980, Butlin 1983).

By the 1850's the traditional Aboriginal economy had largely been replaced by an economy based on European commodities and supply points. Reduced population, isolation from the most productive grasslands, and the destruction of traditional social networks meant that the final decades of the region's semi-traditional indigenous culture and economy was centred around white settlements and properties (Officer 1989).

By 1856 the local 'Canberra Tribe', presumably members of the Ngunnawal, were reported to number around seventy (Schumack 1967) and by 1872 recorded as only five or six 'survivors' (Goulburn Herald 9 Nov 1872). In 1873 one so-called 'pure blood' member remained, known to the white community as Nelly Hamilton or 'Queen Nellie'.

Combined with other ethnohistoric evidence, this lack of early sightings of Aborigines led Flood (1980) to suggest that the Aboriginal population density in the Canberra region and Southern Uplands was generally quite low.

Frequently, only 'pure blooded' individuals were considered 'Aboriginal' or 'tribal' by European observers. This consideration made possible the assertion of local tribal 'extinctions'. In reality, 'Koori' and tribal identity remained integral to the descendants of the nineteenth century Ngunnawal people, some of whom continue to live in the Canberra-Queanbeyan-Yass region.

5.2 Regional Background for the Campbell Precinct

A number of archaeological studies have been carried out in areas east of Canberra City and in the general region around Fairbairn Avenue. Studies have been conducted in the Majura Valley (Winston-Gregson 1985; AASC 1995, 1998; Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1998, 1999a & b,

2001, 2006) and Campbell (Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1997).

Studies conducted in the Majura Valley to the northeast and east of Fairbairn Avenue have assessed a variety of landscape types.

In 1998 AASC conducted a cultural heritage survey of the Army’s Majura Field Firing Range at Majura, an area of approximately 39.5 km2. An estimated 15% of the study area was sampled by the survey, with survey transects biased toward existing ground exposures and riparian zones. Ground surface visibility encountered by the survey was 'on average low to moderate across the entire study area’ and it was considered that the 'effective survey coverage' obtained was sufficient to have provided an effective assessment (AASC 1998:23). This study is, however, limited by a generalised and qualitative landform analysis and site specific management recommendations.

Forty two Aboriginal sites were recorded during the Majura Field Firing Range study. The majority of Aboriginal sites were small scatters of stone artefacts with the largest scatter containing thirty visible artefacts. Five scarred trees were also recorded. Two hundred and twenty two stone artefacts were recorded within the total assemblage for the Firing Range.

Forty two Aboriginal sites were recorded during the Majura Field Firing Range study. The majority of Aboriginal sites were small scatters of stone artefacts with the largest scatter containing thirty visible artefacts. Five scarred trees were also recorded. Two hundred and twenty two stone artefacts were recorded within the total assemblage for the Firing Range.

A detailed cultural heritage survey and assessment of a preferred Majura Valley Transport Corridor easement (Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1999a) was conducted as part of a broader study investigating an appropriate alignment for the future construction of the Majura Parkway between the Federal Highway and Fairbairn Avenue. The proposed transport corridor was situated generally (within) 500 m west of the actual fluvial streamline of Woolshed Creek. The results of background research and field survey indicated that three Aboriginal artefact scatter sites were located within or close to the proposed easement.

In 1999(b) Navin Officer Heritage Consultants was commissioned to undertake a project to identify places and areas of possible cultural heritage significance in those parts of the Majura Valley not already examined for cultural heritage values. Prior to this study, Thirty two Aboriginal sites and isolated finds had been recorded. These included seventeen open artefact scatters, one scarred tree, thirteen isolated finds and one artefact scatter with associated reported quarry or stone procurement site. The 1999(b) field survey resulted in a further nineteen artefact scatters, twenty six isolated finds, three scarred trees and one potential archaeological deposit being recorded for the valley.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants (1999b) noted a broad trend toward Aboriginal site location in valley floor and basal slope contexts. Within the small-scale landform categories, the most frequently recorded site contexts were: spurlines (41%), minor streamline margins (30%), major streamline margins (24%), terrace and alluvial flats (19%), basal slopes (17%), crests (14%), and mid slopes (12%). These frequencies indicate a preference for contexts which are locally elevated, have level ground, and are in close proximity (up to 100 m) to a water source. Riparian zones and mid valley to valley floor context spurline crests were considered to be the most archaeologically sensitive landforms within the Majura Valley. The potential archaeological resource within alluvial and valley floor contexts was possibly significantly under-represented due to the difficulty in detecting sites in aggrading and sedimentary contexts.

Southeast of the Fairbairn Avenue study area Trudinger (1989) conducted research for her Litt B thesis on artefact occurrences within the source bordering sand deposits north of the Molonglo River at Pialligo.

An assessment of alternative options for the proposed John Dedman Drive (Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1997) included an Option 5 - which crossed Fairbairn Avenue at Northcott Drive. The option was not subject to field survey. However, based on geomorphological characteristics and degrees of landuse disturbance, the section of route crossing Fairbairn Avenue was assessed as having some potential to contain Aboriginal sites and requiring archaeological survey.

Cultural heritage assessment of two duplication options for the upgrade of Fairbairn Avenue to dual carriageway from Anzac Parade to Morshead Drive was undertaken in 2001 (Navin Officer Heritage Consultants). Field survey involved the Fairbairn Avenue route options and locations of the proposed traffic circles at Treloar Cresent and Northcott Drive. One low-density surface scatter of Aboriginal artefacts was identified adjacent to the intersection with Mount Ainslie Drive. The site (FA1) comprised of six artefacts on the southern side of Fairbairn Drive identified over a vehicle track and associated exposures. The site was assessed as containing minimal scientific value.

During 2006, Navin Officer Heritage Consultants undertook survey for the proposed Majura Parkway to replace the existing Majura Road between Fairbairn Avenue and the Federal Highway. A total of fifty seven previously recorded and newly recorded Aboriginal sites were identified within the study area. The majority of the sites were scatters artefacts and it was observed that such sites are common within the Majura Valley and the ACT in general.

5.3 The Campbell Precinct

No Aboriginal sites have previously been recorded as occurring within the Campbell precinct study area.

5.4 Regional Background for the Mitchell Precinct

5.4 Regional Background for the Mitchell Precinct

Archaeological surveys in the ACT have resulted in the location of numerous archaeological sites in northern Canberra. The most common site type is the open artefact scatter, however scarred trees, grinding grooves, a possible ochre source and lithic raw material sources have also been identified in the area. Surveys and investigations carried out in this area are summarised below.

The Canberra Archaeological Society (CAS) conducted the first archaeological survey in the northern Canberra area in 1975-76. The survey located 'seven sites' and a larger number of 'less significant finds' (Bindon & Pike 1979). These results were re-assessed by Anutech (1984) who concluded that nine sites and fifteen isolated finds had been located by the CAS.

Seven of the nine sites located by the CAS were located close to streamlines, and twelve of the fifteen isolated finds were located within 100-200 m of streamlines.

Other surveys by the Canberra Archaeological Society added substantially to the database of both prehistoric and historic archaeological information for the area (Witter 1984; Winston-Gregson 1986).

Witter (1980) surveyed a 20 m wide easement for a gas pipeline running between Dalton and Canberra. His survey crossed the Yass River and traversed hilly country in the centre of the Upper Yass River catchment. Eleven artefact scatters containing small silcrete flakes and some blades were recorded during the survey. The following year Witter (1981) fully excavated one site (DC2) and collected the surface artefacts from six sites (DC1, DC5, DC6, DC9, DC11 & DC12).

More generalised studies were conducted for the EIS prepared for the Gungahlin development release area (Anutech 1984, NCDC 1989) and for the compilation of the Sites of Significance volume on Gungahlin and Belconnen (NCDC 1988). The Anutech investigation identified several general consistencies in site location. A majority of sites were classed as located on creek banks, on low- lying but well-drained areas, and within 150 m of the junction of two creeks. This was postulated to indicate a preference for topographically confined parts of valley floors where protection from wind is greatest. At a majority of sites, artefactual material was exposed as subsurface material eroding from A horizon sediments (Anutech 1984:24).

Although this model was considered to be incorrect by some researchers (Access Archaeology 1991:8) further comparative work by Navin and Officer (1991, 1992) tended to confirm the locational model proposed by Anutech. The majority of open artefact scatters, particularly larger sites, are situated adjacent to or in close proximity to creek flats or valley bottom contexts, frequently on low gradient basal slopes adjacent to streams.

With the release of large areas of land for urban development in north Canberra several larger scale systematic archaeological surveys were undertaken to define the archaeological resource of the subject areas (eg Officer and Navin 1992; Kuskie 1992; Wood & Paton 1992). Numerous other archaeological assessments have been carried out for smaller land areas which were likely to be affected by specific proposed developments such as roads, golf courses, water storage facilities, pipelines etc.

The closest archaeological investigation to the present study area is a survey of a proposed gas pipeline easement from the Federal Highway to Majura Parkway conducted by Saunders (1995). No sites were located during the course of the survey.

Navin (1992) undertook a reconnaissance level archaeological survey carried out for a proposed release of land for urban infill purposes at North Watson, and heritage investigations for the duplication of a 10.7 km section of the Federal Highway in North Canberra (Navin, Officer and Legge 1995, 1996).

In 1992 a reconnaissance level archaeological survey was carried out for a proposed release of land for urban infill purposes at North Watson. The area comprised approximately 200 ha of low gradient slopes and foothills on the western fall of Mount Majura. Spurs and drainage lines in the area were generally broad and poorly defined and there were no major drainage beds or permanent water sources in the area. Vegetation consisted of open woodland with isolated or relict scatters of mature

Eucalypts situated within established pasture. Around 40% of the study area had undergone extensive landscape disturbance as a result of a variety of developments.

Eucalypts situated within established pasture. Around 40% of the study area had undergone extensive landscape disturbance as a result of a variety of developments.

The North Watson study area as a whole was considered to have low archaeological potential. This was based on the lack of permanent water, major drainage lines, and economic rock types, and the degree of recent landscape disturbance. Features of relative archaeological potential were defined as mature native trees, relatively undisturbed streamlines and comparatively flat topographic land units (particularly where close to water).

In August 1995 a corridor selection study was undertaken which assessed two possible Federal Highway duplication alternatives (Navin, Officer and Legge 1995) and subsequently further detailed studies were undertaken for the EIS for the duplication (Navin, Officer and Legge 1996). Thus five Aboriginal sites and four isolated finds were located in the Federal Highway Duplication study area.

During 2004, Navin Officer Heritage Consultants undertook survey of Blocks 2 and 3, Section 75, Watson for redevelopment as a residential precinct. Two Aboriginal sites (CF1 and CF2) comprising of artefact scatters were identified on the surface of eroded contexts. Site CF1 was situated on a sloping adjacent to a remnant creek line while site CF2 was identified on sloping ground of a spurline crest. It was noted that both sites did not represent in situ material and there appeared to be little potential for subsurface deposits (Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 2004).

5.5 The Mitchell Precinct

No Aboriginal sites have previously been recorded as occurring within the Mitchell precinct study area.

6.1 Aboriginal Sites

No Aboriginal sites have been previously identified within the Australian War Memorial Campbell and Mitchell Precinct study areas.

No Aboriginal sites or areas of archaeological potential/sensitivity were identified in the Mitchell Australian War Memorial Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation.

One Aboriginal site, isolated find (AWM1), was identified in the Campbell Australian War Memorial Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation. No areas of archaeological potential/sensitivity were identified. The location of the site is shown in Figure 6.3.

Australian War Memorial 1 (AWM1) – isolated find

MGA Ref: 695659.6093524 (GDA) {using hand-held GPS unit} CSMG Ref: 212822.603746 [using GEOMIN32 conversion program]

This recording consists of an isolated stone artefact situated to the west of Treloar Crescent, in the eastern corner of the Australian War Memorial, Campbell precinct. The artefact was identified on an exposure on the crest of a slight rise, adjacent to the road (Figures 6.1 and 6.2). The find is situated 3 m from the road and approximately 20 m north of Treloar Crescent and Fairbairn Avenue junction.

Significant ground disturbance associated with the installation of a gas pipeline and the spreading of road metal has occurred within the artefact location.

The isolated find is a commonly occurring artefact type and is made from commonly occurring stone type. The flake occurs as a 'loose', possibly lagged or disturbed surface feature. The potential for subsurface and in situ artefactual material to remain at this site is considered to be minimal due to the shallow nature of the soil and the extent of previous ground disturbance.

Ground exposure in the area was estimated at 80% with 30% visibility in the area of exposure. Artefact recorded at this location:

1. brown grey volcanic broken flake; 23 x 17 x 3 mm

Figure 6.1 View looking north towards site Australian War Memorial 1 (AWM1) - artefact is situated on rise crest within exposure

Figure 6.2 View of site Australian War Memorial 1 (AWM1) looking south along exposure towards junction of Treloar Crescent and Fairbairn Avenue, Campbell

Figure 6.3 Location of Aboriginal site within the Australian War Memorial, Campbell precinct (Extract from Canberra 1:25,000 topo map 2nd edition L&PI 2003)

6.2 Survey Coverage and Visibility Variables

The effectiveness of archaeological field survey is to a large degree related to the obtrusiveness of the sites being looked for and the incidence and quality of ground surface visibility. Visibility variables were estimated for all areas of comprehensive survey within the study area. These estimates provide a measure with which to gauge the effectiveness of the survey and level of sampling conducted. They can also be used to gauge the number and type of sites that may not have been detected by the survey.

Ground surface visibility is a measure of the bare ground visible to the archaeologist during the survey. There are two main variables used to assess ground surface visibility, the frequency of exposure encountered by the surveyor and the quality of visibility within those exposures. The predominant factors affecting the quality of ground surface visibility within an exposure are the extent of vegetation and ground litter, the depth and origin of exposure, the extent of recent sedimentary deposition, and the level of visual interference from surface gravels.

The incidence of ground surface exposure at the Campbell Precinct varied enormously across the site with greater exposure and visibility in the eastern portion of the study area. It was estimated that 20% ground exposures with 30% visibility within the exposures characterised the eastern half while this decreased significantly across the western portion of the Campbell site. The low level of visibility for an open context is due to the thick grass coverage from extensive landscaping.

The incidence of ground exposure at the Mitchell precinct was limited to a small portion of highly disturbed ground within Treloar A measuring approximately 80 x 40 m. Visibility within this area was estimated at 40% with coverage of imported gravels.

7. SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT

7. SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT

7.1 Commonwealth Heritage Assessment Criteria

The Commonwealth Heritage List is a register of natural and cultural heritage places owned or controlled by the Australian Government. These may include places associated with a range of activities such as communications, customs, defence or the exercise of government. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 establishes this list and nominations are assessed by the Australian Heritage Council.

In accordance with the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 a place has a Commonwealth Heritage value if it meets one of the Commonwealth Heritage criteria (section 341D).

A place meets the Commonwealth Heritage listing criterion if the place has significant heritage value because of one or more of the following:

a) The place's importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia's natural or cultural history;

b) The place's possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Australia's natural or cultural history;

c) The place's potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia's natural or cultural history;

d) The place's importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of:

ii. a class of Australia's natural or cultural environments;

e) The place's importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics valued by a community or cultural group;

f) The place's importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period;

g) The place's strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons;

h) The place's special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Australia's natural or cultural history; and

i) The place's importance as part of Indigenous tradition.

Thresholds

While a place can be assessed against the above criteria for its heritage value, this may not always be sufficient to determine whether it is worthy of inclusion on the Commonwealth Heritage List. The Australian Heritage Council may also need to use a second test, by applying a 'significance threshold', to help it decide. This test helps the Council to judge the level of significance of a place's heritage value by asking 'just how important are these values?'

To be entered on the Commonwealth Heritage List a place will usually be of local or state-level significance.

Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles

Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles

In addition to the above criteria and thresholds, Schedule 7B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Regulation 10.03D) lists the Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles. These principles are:

2. The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should use the best available knowledge, skills and standards for those places, and include ongoing technical and community input to decisions and actions that may have a significant impact on their Commonwealth Heritage values.

3. The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should respect all heritage values of the place and seek to integrate, where appropriate, any Commonwealth, State, Territory and local government responsibilities for those places.

4. The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should ensure that their use and presentation is consistent with the conservation of their Commonwealth Heritage values.

5. The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should make timely and appropriate provision for community involvement, especially by people who:

a) Have a particular interest in, or associations with, the place; and

b) May be affected by the management of the place.

6. Indigenous people are the primary source of information on the value of their heritage and that the active participation of indigenous people in identification, assessment and management is integral to the effective protection of indigenous heritage values.

7. The management of Commonwealth Heritage places should provide for regular monitoring, review and reporting on the conservation of Commonwealth Heritage values.

When assessing the Commonwealth heritage significance of places within the study area, in addition to applying the primary and secondary tests of the Commonwealth Heritage Listing criteria and the significance thresholds, reference also needs to be made to the above Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles. The latter is particularly relevant to the study area where there are:

Given its disturbed context and the lack of rare or notable features, the archaeological significance of isolated find AWM1 is considered to be low. However, all Aboriginal archaeological recordings retain significance for the local Aboriginal community. Aboriginal representative Mr Don Bell expressed concern that the Aboriginal recording within the Campbell study area be protected as much as possible from any potential direct impacts resulting from any future development.

As representatives of ACT Aboriginal stakeholder groups have indicated that the isolated find, AWM1, recorded in the Campbell Precinct is valued by the local Aboriginal community as important as part of the local indigenous tradition, the site meets Criterion (i) of the Commonwealth Heritage Listing criteria.

Further, as the site is considered to have significant heritage value to local Aboriginal community groups it meets the threshold for recording on the Commonwealth Heritage List.

8. STATUTORY INFORMATION1

8. STATUTORY INFORMATION1

8.1 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

This Act (EPBC Act) repeals the Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974, the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975, the Whale Protection Act 1980, the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983, and the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992. The scope and coverage of the Act is wide and far-reaching. The objectives of the Act include: the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of national significance; to promote the conservation of biodiversity and ecologically sustainable development; and to recognise the role of indigenous people and their knowledge in realising these aims.

The Act makes it a criminal offence to undertake actions having a significant impact on any matter of national environmental significance (NES) without the approval of the Environment Minister. Actions which have, may have or are likely to have a relevant impact on a matter of NES may be taken only:

Matters of national environmental significance (NES) are defined as:

In addition, the Act makes it a criminal offence to take on Commonwealth land an action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment (section 26(1)). A similar prohibition (without approval) operates in respect of actions taken outside of Commonwealth land, if it has, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land (s26(2)). Section 28, in general, requires that the Commonwealth (or its agencies) must gain approval (unless otherwise excluded from this provision), prior to conducting actions which has, will, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment inside or outside the Australian jurisdiction.

The Act adopts a broad definition of the environment that is inclusive of cultural heritage values. In particular, the ‘environment’ is defined to include the social, economic and cultural aspects of ecosystems, natural and physical resources, and the qualities and characteristics of locations; places and areas (s528).

The Act allows for several means by which a controlled action can be assessed, including an accredited assessment process, a public environment report, an environmental impact statement, and a public inquiry (Part 8).

![]()

1 The following information is provided as a guide only and is accurate to the best knowledge of Navin Officer Heritage Consultants. Readers are advised that this information is subject to confirmation from qualified legal opinion.

Section 68 imposes an obligation on a proponent proposing to take an action that it considers to be a controlled action, to refer it to the Environment Minister for approval.

Section 68 imposes an obligation on a proponent proposing to take an action that it considers to be a controlled action, to refer it to the Environment Minister for approval.

World heritage values are defined to be inclusive of natural and cultural heritage (s12(3)), and a declared World Heritage Property is one included on the World Heritage List, or is declared to be such by the Minister (s13 and s14). The Act defines various procedures, objectives and Commonwealth obligations relating to the nomination and management of World Heritage Properties (Part 15, division 1).

8.2 Environment and Heritage Legislation Amendment Act (No 1) 2003

Australian Heritage Council Act 2003 and

Australian Heritage Council (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Act 2003

These three Acts replace the previous Commonwealth heritage regime instigated by the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975. The Acts establish the following provisions:

The National Heritage List

The National Heritage List is a schedule of places which the Minister for the Environment and Heritage considers to have ‘National Heritage Value’ based on prescribed ‘National Heritage Criteria’. The List many include places outside of Australia if agreed to by the Country concerned. There is a public nomination process and provision for public consultation on nominations. Expert advice regarding nominations is provided to the Minister by the Australian Heritage Council.

A nominated place considered to be at risk can be placed on an emergency list while its heritage value is assessed.

The listing of a place is defined as a ‘matter of national environmental significance’ under the EPBC Act. As a consequence, the Minister must grant approval prior to the conduct of any proposed actions which will, or are likely to have, a significant impact on the National Heritage values of a listed place.

The Minister is to ensure that there are approved management plans for most listed places owned or controlled by the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency, and that Commonwealths actions are in accord with such plans.

The Commonwealth or its agencies cannot sell or lease a listed place unless the protection of its National Heritage values is specified in a covenant, or such an action is found to be unnecessary, unreasonable or impractical. All Commonwealth agencies which own or control places which have or may have National Heritage values, must take all reasonable steps to assist the Minister and Australian Heritage Council to identify and assess those values.

The Commonwealth Heritage List

The Commonwealth Heritage List is a schedule of places owned or controlled by the Commonwealth, which the Environment Minister considers to have ‘Commonwealth Heritage Value’. The list may include places outside of Australia. The processes of nomination and assessment are similar to those for the National Heritage List. Like the National Heritage List, there is a provision for emergency listing.

The Act places a range of obligations on the Commonwealth Agencies with regard to places included on the Commonwealth Heritage List. These include:

Ensuring that no action is taken which has, will have, or is likely to have an adverse impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage Place, or the Commonwealth Heritage values of a Commonwealth Heritage Place, unless there is no feasible or prudent alternative and all reasonable measures to mitigate impact have been taken; and

Ensuring that no action is taken which has, will have, or is likely to have an adverse impact on the National Heritage values of a National Heritage Place, or the Commonwealth Heritage values of a Commonwealth Heritage Place, unless there is no feasible or prudent alternative and all reasonable measures to mitigate impact have been taken; and

The Australian Heritage Council

The Australian Heritage Council provides expert advice to the Minister on heritage issues and nominations for the listing of places on the National Heritage List and the Commonwealth Heritage List. The Council replaces the former Australian Heritage Commission.

The Register of the National Estate

The register of the National Estate was established under the now repealed Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975. The National Estate was defined under this Act as ‘those places, being components of the natural environment of Australia or the cultural environment of Australia, that have aesthetic, historical, scientific or social significance or other special value for future generations as well as for the present community’. Under the new Commonwealth Acts, the Register will be retained and maintained by Australian Heritage Council as a publicly accessible database for public education and the promotion of heritage conservation. Nominations will assessed by the Australian Heritage Council. The Minister must consider the information in the Register when making decisions under the EPBC Act. A transitional provision allows for the Minister to determine which of the places on the Register and within Commonwealth areas should be transferred to the Commonwealth Heritage List.

9. CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

9. CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

No Aboriginal sites or areas of archaeological potential/sensitivity were identified in the Mitchell Australian War Memorial Mitchell Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation. There are no indigenous heritage assets or constraints relating to the Australian War Memorial Mitchell Precinct.

One Aboriginal site, isolated find, AWM1, was identified in the Australian War Memorial Campbell Precinct study area in the course of the current investigation. The site has low archaeological values, but is valued by the local Aboriginal community and as such it meets Criterion (i) of the Commonwealth Heritage Listing criteria.

It is recommended that:

2. Impact to site AWM1 should be avoided, if disturbance is anticipated potential activities around the periphery of the site should be managed and the site fenced where appropriate to demarcate site boundary and to control access.

3. A copy of this report should be provided to the following Aboriginal organisations with an invitation to comment on the report findings and recommended management strategies:

Mr Tyrone Bell

Buru Ngunawal Aboriginal Corporation 4 Gasking Place

DUNLOP NSW 2615

Mr Carl Brown CBAC

17 Cassia Crescent

QUEANBEYAN NSW 2620

Mr Tony Boye

Ngarigu Currawong Clan 6 Buckman Place

MELBA ACT 2615

10. REFERENCES

10. REFERENCES

AASC 1995 Brief No 94/13 - Preliminary Cultural Resource Surveys of Potential Motor Sports Sites at Kowen and Majura. Report to ACT Planning Authority, Dept of Environment, Land & Planning, ACT Government.

AASC 1998 DRAFT Cultural Heritage Survey of Majura Field Firing Range, Majura, ACT. Report to the Department of Defence.

Access Archaeology P/L 1991 John Dedman Drive Archaeological Survey. Report to Ove Arup & Partners; R.A. Young & Associates.

Anutech Archaeological Consultancies 1984 An Archaeological Study of Gungahlin, ACT Vols 1 & 2.

Report to N.C.D.C, Canberra.

Bindon, P. and G. Pike 1979 Survey of Prehistoric and Some Historic Sites of the Gungahlin District, ACT. Conservation Memorandum No 6, ACT Parks and Conservation Service, First Edition.

Butlin, N. 1983 Our Original Aggression. Allen and Unwin, Sydney. Flood, J. 1980 The Moth Hunters AIAS Press, Canberra.

Kuskie, P.J. 1992 A Preliminary Cultural Resource Survey of the Proposed Residential Development Areas C1, C2, C3 & C4 at Gungahlin, ACT. Report to ACT Dept of Environment, Land and Planning.

Navin, K. 1992 Reconnaissance Level Investigation of North Watson, ACT. Report to Ove Arup and Partners Pty Ltd.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1997 Cultural Heritage Assessment Proposed John Dedman Drive and Alternative Options. Report to Maunsell McIntyre Pty Ltd.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1998 Inventory of Known and Reported Cultural Heritage Places, Majura Valley ACT. Desktop Review for Proposed Majura Valley Transport Corridor. Report to Gutteridge Haskins & Davey Pty Ltd.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1999a Majura Valley Transport Corridor Cultural Heritage Assessment. Report to Gutteridge Haskins & Davey Pty Ltd.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 1999b Survey and Assessment of the Cultural Heritage Resource of part of the Majura Valley, Woolshed Creek, ACT. 2 vols. A Report to the Heritage Unit, Environment ACT, ACT Dept of Urban Services.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 2001 (revised 2003) Fairbairn Avenue Duplication, Cultural Heritage Assessment. A Report to David Hogg Pty Ltd.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 2004 Part Block 2 and Block 3 Section 75, Watson ACT. Cultural Heritage Assessment. A Report to McCann Property & Planning.

Navin Officer Heritage Consultants 2006 Majura Parkway, Majura Valley, ACT. Cultural Heritage Assessment. A Report to SMEC Australia.

Navin, K and K. Officer 1991 An Archaeological Investigation of Site PH44, Gungahlin. Report to Ove Arup and Partners Pty Ltd.

Navin, K and K. Officer 1992 An Archaeological Survey of Sections of the Proposed Gundaroo and Mirrabei Drives, Gungahlin, ACT. Report R. A. Young and Associates Pty Ltd.

Navin, K., K. Officer and K. Legge 1996 Proposed Duplication Of The Federal Highway, Stirling Avenue to Sutton Interchange EIS - Cultural Heritage Component. Report to Ove Arup & Partners

Navin, K., K. Officer and K. Legge 1996 Proposed Duplication Of The Federal Highway, Stirling Avenue to Sutton Interchange EIS - Cultural Heritage Component. Report to Ove Arup & Partners

NCDC 1989 Gungahlin Environmental Impact Statement. NCDC, Canberra.

Officer, K. 1989 Namadgi Pictures The Rock Art Sites within the Namadgi National Park, ACT. Their recording, significance, analysis and conservation. Volumes 1 and 2.

Officer, K. and K. Navin 1992 An Archaeological Assessment of the May 1992 Urban Release Areas, Gungahlin, ACT. Report to the ACT Heritage Unit.

Saunders, P. 1995 Cultural Heritage Survey of Gas Pipeline from Federal Highway to Majura Parkway, ACT. Report to Navin Officer for AGL Gas Company (ACT) Pty Ltd.

Schumack, S.1967 An Autobiography or Tales and Legends of Canberra Pioneers. ANU Press Canberra

Tindale, N. 1940 Australian Aboriginal Tribes: A Field Survey. Transactions Royal Society of S.A. No 64.

Trudinger, P. 1989 Confounded by Carrots. Unpublished Litt.B Thesis. Dept of Prehistory & Anthropology, ANU.

Walker, P. H. 1978 Soil-Landscape Associations of the Canberra Area. Division of Soils Divisional Report No.29, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia.

Winston-Gregson, J. H. 1985 Australian Federal Police Site at Majura Block 42, Archaeological Report. Access Archaeology Pty Ltd. Report to National Capital Development Commission (Brief no. EL 55/84).

Winston-Gregson, J. H. 1986 Percival Hill Archaeological Survey. Report to N.C.D.C, Canberra.

1986.

Witter, D. 1980 An Archaeological Pipeline Survey between Dalton and Canberra. Aboriginal and Historical Resource Section, NPWS, Sydney.

Wood, V. and R. Paton 1992 Cultural Resource Assessment of Area C5, Gungahlin, ACT: Stage 1.

Report to ACT DELP.

~ o0o ~

APPENDIX 1

ABORIGINAL PARTICIPATION FORMS

Appendix J

Memorial Stakeholder and Community Consultation

Stakeholder and Community Consultation

A stakeholder is defined by the Memorial as someone who is interested in, who can influence, or may be impacted by heritage matters at the AWM. These stakeholders may be from within the Memorial, individuals or community groups, as listed below.

The AWM Heritage Strategy, Heritage Management Plan or any future works, projects or activities may be of interest to stakeholders. The Memorial’s Building and Services Section determine who the relevant stakeholders are for consultation in relation to heritage matters. This occurs on a case-by-

case basis and would be determined where the stakeholders’ interests, skills or expertise, matches

the heritage matter being considered and requiring consultation.

Consultation involves stakeholder engagement in the most suitable forum for the matter or project being considered, and is based upon an understanding of already identified understanding, familiarity and appreciation of heritage matters.

The Memorial undertakes consultation to ensure all stakeholders have a genuine opportunity to engage with the particular heritage-related matter or project. The Memorial’s consultation aims to reflect their particular expertise, or aspirations and to ensure the Stakeholders are aware, informed and engaged with the conservation of the National and Commonwealth Heritage values of the AWM.

Stakeholder Identification

Key heritage stakeholder groups include:

![]()

Stakeholder & Community Consultation Guidelines, May 2020 Page 1

Appendix K

EPBC Referral 2019-8574 Approval Conditions

VARIATION OF CONDITIONS ATTACHED TO APPROVAL

Australian War Memorial Redevelopment, Campbell, ACT (EPBC 2019/8574)

This decision to vary conditions of approval is made under section 143 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

Person to whom the approval is granted | Australian War Memorial

ABN: 64 909 221 257 |

Approved action | To undertake the Australian War Memorial Redevelopment works, Campbell, ACT. The works are to increase display space and improve visitor amenity and include a new Southern Entrance below the existing forecourt, expansion of the Parade Ground, demolition and reconstruction of Anzac Hall and a new Glazed Courtyard between the rear of the Memorial and the new Anzac Hall, extension and refurbishment of the C.E.W. Bean Building, a new Research Centre and Public Realm improvement works [as described in EPBC referral 2019/8574, the final Preliminary Documentation dated September 2020 and subject to the approved variation dated 17 March 2020]. |

Variation

Variation of conditions attached to approval | The variation is:

Delete conditions 3, 5, 6, 10, 14, and 15 attached to the approval and substitute with the conditions specified in the table below

Delete Appendix A1 and substitute with the Appendix A1 specified in the table below. |

Date of effect | This variation has effect on the date the instrument is signed |

Person authorised to make decision

Name and position | Kim Farrant Assistant Secretary Environment Assessments (Vic, Tas) and Post Approvals Branch |

Signature |

|

Date of decision |

27 May 2021 |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

| Part A – Conditions specific to the action |

Original dated 10 | Removal and reinstatement of Main Building fabric |

December 2020 |

|

Original | 2. To minimise the impact of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must:

|

dated 10 | |

December | |

2020 | |

As varied on the date this | Managing Construction Impacts |

instrument was signed | 3. To minimise the impact of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must implement protection measures to ensure that fabric of the Main Building is managed and monitored during construction works to ensure no structural damage occurs in accordance with Appendix A1. |

| These measures must include as a minimum: |

| a. Engaging a suitably qualified expert to: i. Oversee and inspect the demolition and removal of building material to ensure there is no unapproved removal of Main Building fabric or elements other than the impacts identified in Appendix A1; |

| ii. Advise on procedures to handle and monitor impacts to Main Building fabric; |

| iii. Provide ongoing advice throughout the construction period including measures to manage traffic and laydown areas to reduce the risk of accidental impacts to the heritage values of the site; |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

| iv. Undertake regular inspections (on a daily basis or continuously during critical stages) throughout the construction of the new Southern Entrance to minimise impacts to the Main Building fabric.

b. Installing appropriate vibration sensors in the Main Building with threshold limits and alarms to detect any structural movement during bulk excavation and construction works and cease work if threshold limits are exceeded and/or structural impacts are detected; c. Establishing a minimum 1.5 metre heritage buffer zone along the Main Building southern facade in accordance with Appendix A1 to reduce the risk of structural impacts to the fabric of the Main Building. The heritage buffer zone must be clearly marked and façade physically protected. d. Underpinning of the towers consistent with Appendix A1 to ensure structural integrity of the Main Building is maintained throughout the new Southern Entrance works; e. Identifying and implementing contingency measures approved by a suitably qualified expert (structural engineer) in the case that structural impacts to the Main Building are detected during the construction phase.

These measures must be established prior to the commencement of construction and maintained throughout the duration of construction activities. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 4. To minimise the impact of the action on protected matters during the construction phase, the approval holder must document prior to commencement of construction and implement appropriate measures to: |

| a. Protect all onsite mature trees that are not planned for removal (i.e. exclusion fencing). |

| b. Clear only one hollow bearing tree in accordance with Figure 1. |

| c. Prevent soil erosion and stormwater contamination and implement contingency measures in the event of an impact being detected. |

| d. Monitor and manage any underground storage tanks to prevent soil and groundwater contamination. |

| e. Prevent any impacts to known Aboriginal Cultural Heritage sites in accordance with Figure 2. |

| f. Quickly detect any previously unknown items of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage that are encountered during construction, and immediately stop any works that could cause impacts until consultation with Registered Aboriginal Organisations results in agreement to resume works. |

| g. Induct construction personnel so that they are aware of the National and Commonwealth Heritage values and the Aboriginal Cultural heritage values of the site. |

| These measures must be established prior to the commencement of construction and maintained throughout the duration of construction activities. |

As varied on the date this | Archival Recording of Australian War Memorial Site |

instrument was signed | 5. To minimise the impact of the action on protected matters, prior to the commencement of construction, the approval holder must: a. Prepare a photographic archival record of the existing landscape and built features of the whole Australian War Memorial (Memorial) site prior to |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

| commencement of construction and throughout the development process in accordance with the document Photographic Recording of Heritage Items Using Film or Digital Capture (NSW Heritage Office, 2006). The archival record must be made available to the public by being permanently published on the website as a minimum. b. Commence a research project prior to commencement of construction to document the public's interpretation of historic elements of the site to allow the interpretation of the architectural development of the site and complete within 12 months of commencement of construction. c. Commence a research project prior to commencement of construction to document record and archive the memories that designers, veterans and visitors have of Anzac Hall and make the archive publicly available on the website within 12 months of commencement of construction. |

As varied on the date this instrument was signed | Specific Building Design Requirements

6. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must ensure all detail design is consistent with the requirements of: |

| a. National Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade. |

| b. Commonwealth Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial. |

| c. Commonwealth Heritage values of the Parliament House Vista. |

| d. National Heritage Management Principles and |

| e. Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles |

| A Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) evaluating the final design against the above requirements must be conducted by a suitably qualified person prior to the commencement of construction. The HIA must be submitted to the Minister for approval prior to commencement of construction. The approval holder must not commence construction unless the HIA has been approved by the Minister in writing. The approval holder must implement the approved HIA. The approved HIA must be made publicly available on the website prior to commencement of construction and remain published on the website for the duration of this approval. |

| The HIA must be updated in accordance with conditions 14 and 15 and then submitted to the Department within 20 business days following any National Capital Authority (NCA) approval, to document any landscape and/or public realm design and any detailed design changes required by the NCA. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 7. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must ensure that the apex of the Glazed Link and the roof of new Anzac Hall do not exceed RL 602.700m as shown in Appendix B1. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 8. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters the approval holder must:

a. Design, engineer and install a Glazed Link that can be removed without damage to the existing Main Building stone facade in the future if necessary, in accordance with Appendix B4. |

| b. Ensure the Glazed Link roof is only attached to the Main Building's 1990's metal roof addition and the existing roof slab/structure underneath. |

| c. Ensure the outline of the Glazed Link roof is installed to allow the parapet shape of the Main Building to be visible from Mount Ainslie. |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

| d. Maximise the transparency of the Glazed Link roof to promote the view of the northern façade of the Main Building in accordance with Appendix B2 and Appendix B3. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 9. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters the approval holder must:

a. Ensure the Oculus dome is constructed of low reflectivity glass (maximum external reflectivity of 10%). |

| b. Ensure the Oculus dome height does not exceed 530mm above the forecourt ground level. |

| c. Ensure the angled flat bronze handrail surrounding the Oculus does not exceed 750mm in height from forecourt ground level and does not contain glass infill. |

| d. Ensure the surrounding stone kerb is 250mm in height from forecourt ground level. |

As varied on | 10. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters the approval holder must:

|

the date this | |

instrument | |

was signed | |

Original dated 10 | Other Measures to mitigate Heritage Impacts |

December 2020 | 11. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must, in time for the completion of construction, and for the remainder of the duration of this approval, train staff and volunteers to assist visitors to understand and appreciate the importance of the ability to view the Main Building northern facade when viewed within the Glazed Link in relation to the National Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade and the Commonwealth Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 12. To minimise the impact of the action on protected matters the approval holder must retain the access to the existing Main Building heritage entrance and promote its importance as recognised in the National Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade and the Commonwealth Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial, the approval holder must: |

| a. Retain the use of the existing main entrance to the Main Building at the completion of construction for all visitors. |

| b. Retain modest cloaking/security services at the existing entrance to ensure visitors can still access this entrance directly. |

| c. Erect signage in time for the completion of construction to include an option for visitors to proceed directly between the carparks and the existing Main Building entrance; |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

| d. Ensure visitor engagement technology at the new Southern Entrance supports the understanding of the history and importance of entering the Commemorative Area through the existing Main Building entrance.

e. Train staff and volunteers in time for the completion of construction, and for the remainder of the duration of this approval, to assist visitors to understand and appreciate the importance of the existing Main Building entrance. |

Original | 13. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must use materials sympathetic in colour, finish and design to the Australian War Memorial's existing built heritage fabric and vistas for all new buildings and extensions. |

dated 10 | |

December | |

2020 | |

As varied on the date this instrument was signed | 14. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must:

|

| i. C.E.W Bean Building extension and Research Centre building finishes and heights |

| ii. New Anzac Hall building and roof finishes |

| iii. Glazed Link roof material and finish |

| iv. Handrail design and finish at Main Building front entry stairs |

| v. Glazed link attachment to Main Building |

| vi. Oculus detail design and handrail finish |

| vii. Glass lift detail design |

| viii. Final Parade Ground layout |

| ix. Final design of any other currently unresolved detailing |

| The approval holder must notify the Minister in writing of the final design and/or finishes of each of the above listed elements prior to, and as submitted for, NCA approval. The final design of the above listed elements must be included in the Heritage Impact Assessment required by condition 6. |

| The approval holder must provide written evidence that the design and/or finishes are supported by the NCA prior to commencing construction of each element detailed above. |

| Any specific detailed design changes required to satisfy NCA requirements must be fully documented and an updated HIA prepared in accordance with condition 6 and provided to the Department prior to construction of that element. |

| b. Finalise the building design for the two new spiral staircases within the Main Building, that form part of the Southern Entrance portion of work prior to the commencement of construction of that element and submit the final design to the Minister. The Heritage Impact Assessment required by condition 6 must include an assessment of the final design of the internal stairs. |

As varied on the date this | 15. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must: |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

instrument was signed |

|

Original | 16. To minimise impacts on protected matters the approval holder must re- use and repurpose as much of the original Anzac Hall building material as practicable consistent with the National Waste Action Plan 2019. |

dated 10 | |

December | |

2020 | |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 17. To minimise impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must:

a. Ensure that all works to the Australian War Memorial maintains the nature of commemoration identified In Criterion (b) of the Natlonal Heritage values of the Australlan War Memorlal and the Memorial Parade and the Commonwealth Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial. This is recognised in equal parts in the relationship between the building, the collection of objects and records and the commemorative spaces. |

| b. Update the Heritage Impact Assessment required by condition 6 within 18 months of the commencement of construction to demonstrate how the finalised site and gallery plan will maintain the nature of commemoration identified in Criterion (b) of the National Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade and the Commonwealth Heritage values of the Australian War Memorial. The updated Heritage Impact Assessment must be submitted to the Minister for approval. The approval holder must implement the approved Heritage Impact Assessment. The approved Heritage Impact Assessment must be made publicly available on the website for the duration of this approval. |

| c. Provide in writing to the Minister in each report required by condition 23, any significant changes to the commemorative spaces (i.e. removal or addition of commemorative spaces) undertaken during or proposed in the period that is the subject of the report and how the relationship between the elements of criterion (b) is being maintained. |

Original | 18. To minimise the impacts of the action on protected matters, the approval holder must implement the revised Parade Ground layout with an area of gravel consistent with the existing Parade Ground area and stone terraced seating not exceeding the lengths shown in Figure 3. |

dated 10 | |

December | |

2020 | |

| Part B – Standard administrative conditions |

Original dated 10 | Notification of date of commencement of the action |

December 2020 | 19. The approval holder must notify the Department in writing of the date of commencement of the action within 10 business days after the date of |

| commencement of the action. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 20. If the commencement of the action does not occur within 10 years from the date of this approval, then the approval holder must not commence the action without the prior written agreement of the Minister. |

Date of decision | ANNEXURE A – CONDITOINS OF APPROVAL |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | Compliance records

21. The approval holder must maintain accurate and complete compliance records. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | 22. If the Department makes a request in writing, the approval holder must provide electronic copies of compliance records to the Department within the timeframe specified in the request.

Note: Compliance records may be subject to audit by the Department or an independent auditor in accordance with section 458 of the EPBC Act, and or used to verify compliance with the conditions. Summaries of the result of an audit may be published on the Department's website or through the general media. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | Annual compliance reporting

23. The approval holder must prepare a compliance report for each 12-month period following the date of commencement of the action, or otherwise in accordance with an annual date that has been agreed to in writing by the Minister. The approval holder must:

following the relevant 12-month period;

b. notify the Department by email that a compliance report has been published on the website and provide the weblink for the compliance report within five business days of the date of publication including documented evidence of the date of publication;

c. keep all compliance reports publicly available on the website until this approval expires;

d. exclude or redact sensitive data from compliance reports prior to publishing them on the website; and

e. where any sensitive data has been excluded from the version published, submit the full compliance report to the Department within 5 business days of publication.

Note: Compliance reports may be published on the Department's website. |

Original dated 10 December 2020 | Reporting non-compliance

24. The approval holder must notify the Department in writing of any: incident; or non-compliance with the conditions. The notification must be given as soon as practicable, and no later than two business days after becoming aware of the incident or non-compliance. The notification must specify:

b. a short description of the incident and/or non-compliance; and

c. the location (including co-ordinates), date, and time of the incident and/or non-compliance. In the event the exact information cannot be provided, provide the best information available. |