COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL AND ANZAC PARADE HERITAGE MANAGEMENT PLANS 2022

I, JAMES BARKER, Branch Head, World and National Heritage Branch, acting as delegate for the Minister for the Environment and Water, acting pursuant to subsection 324S(2) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, hereby revoke the Australian War Memorial Heritage Management Plan 2011 and the Anzac Parade Heritage Management Plan 2013 and replace them with the Australian War Memorial Heritage Management Plan 2022 and the Anzac Parade Heritage Management Plan 2022 (together forming the Australian War Memorial and Anzac Parade Management Plans 2022), to protect and manage the National Heritage values of the National Heritage place, Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade.

This instrument commences on the day after it is registered.

JAMES BARKER

Branch Head, World and National Heritage Branch

Dated 25 March 2024

Australian War Memorial

Heritage Management Plan

Revised Final Report

Report prepared for the Memorial

March 2022

Report Register

The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Australian War Memorial—Heritage Management Plan—Revised Final Report, undertaken by GML Heritage Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system.

Job No. | Issue No. | Notes/Description | Issue Date |

18-0245 | 1 | Draft Report | 4 September 2018 |

18-0245 | 2 | Revised Draft Report | 8 July 2019 |

18-0245 | 3 | Final Draft Report | 5 August 2019 |

18-0245 | 4 | Final Report | 13 September 2019 |

18-0245B | 5 | Revised Final Report | 29 May 2020 |

18-0245B | 6 | Revised Final Report with minor amendments | 26 June 2020 |

18-0245B | 7 | Revised Final Report (DAWE comments amendments) | 8 June 2021 |

18-0245B | 8 | Revised Final Report (DAWE and AWM comments amendments) | 22 June 2021 |

18-0245B | 9 | Revised Final Report (for DAWE review) | 2 July 2021 |

18-0245B | 10 | Revised Final Report (for AHC review) | 12 August 2021 |

18-0256B | 11 | Revised Final Report (AHC Review) | 29 November 2021 |

18-0245B | 12 | Revised Final Report (AHC Amendments) | 11 February 2022 |

18-0245B | 13 | Revised Final Report (minor AHC Amendments) | 10 March 2022 |

Quality Assurance

GML Heritage Pty Ltd operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008.

The report has been reviewed and approved for issue in accordance with the GML quality assurance policy and procedures.

Copyright

Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced at the end of each section and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners.

Unless otherwise specified or agreed, copyright in this report vests in GML Heritage Pty Ltd (‘GML’) and in the owners of any pre-existing historic source or reference material.

Moral Rights

GML asserts its Moral Rights in this work, unless otherwise acknowledged, in accordance with the (Commonwealth) Copyright (Moral Rights) Amendment Act 2000. GML’s moral rights include the attribution of authorship, the right not to have the work falsely attributed and the right to integrity of authorship.

Right to Use

GML grants to the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title) an irrevocable royalty- free right to reproduce or use the material from this report, except where such use infringes the copyright and/or Moral Rights of GML or third parties.

Cover Image: Roll of Honour, AWM. (Source: GML, 2018)

Contents Page

Executive Summary Abbreviations and Definitions | i iii |

Abbreviations | iii |

Australian War Memorial Terms | iv |

Definitions and Terminology | iv |

1.0 Introduction | 1 |

1.1 Background | 1 |

1.2 Previous Heritage and Conservation Management Plans | 1 |

1.3 Location of the Site | 2 |

1.4 Heritage Listings | 3 |

1.5 Heritage Register | 6 |

1.6 Consultation | 6 |

1.7 Endnotes | 7 |

2.0 Understanding the Place—Historical Context | 8 |

2.1 Aboriginal Cultural and Historical Context | 8 |

2.2 Origins and Establishment | 8 |

2.3 Expansion and Evolution | 14 |

2.4 New Meanings | 16 |

2.4.1 The Western Precinct—1999 to Present | 19 |

2.4.2 The Eastern Precinct | 24 |

2.5 Australian War Memorial Development Project 2019-2028 | 25 |

2.5.1 Project Development | 25 |

2.5.2 Initial Business Case (2017) | 25 |

2.5.3 Detailed Business Case—Development of Options | 27 |

2.5.4 Design Development | 37 |

2.5.5 The Replacement of Anzac Hall | 40 |

2.5.6 Project Development Outcomes | 42 |

2.5.7 Community Response to the Development Project and Designs | 43 |

2.5.8 Closure and demolition of Anzac Hall | 43 |

2.6 Endnotes | 44 |

3.0 Understanding the Place—Physical Context | 45 |

3.1 Topographic Context | 45 |

3.2 Physical Description | 45 |

The Main Memorial Building The Main Memorial Building

| 49 |

The Commemorative Area The Commemorative Area

| 49 |

The Galleries The Galleries

| 52 |

The Dioramas The Dioramas

| 55 |

ANZAC Hall ANZAC Hall

| 56 |

The Administration Building The Administration Building

| 57 |

CEW Bean Building CEW Bean Building

| 57 |

Appendix A

Decision Making Process

Appendix B

Heritage Impact Self-Assessment Form

Appendix C

EPBC Regulations Compliance Checklists

Appendix D

NCA Works Approval Application Information Checklists

Appendix E

AWM and Memorial Parade National Heritage List Citation

Appendix F

AWM Commonwealth Heritage List Citation

Appendix G

Parliament House Vista Commonwealth Heritage List Citation

Appendix H

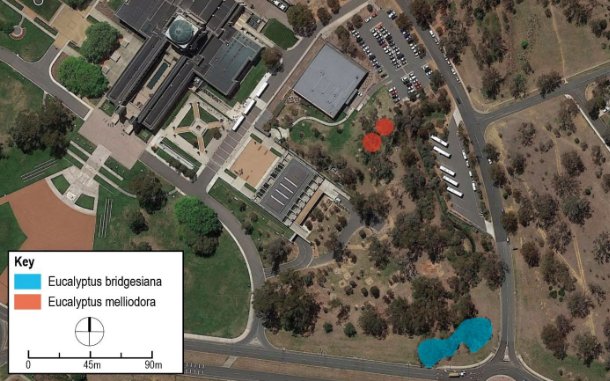

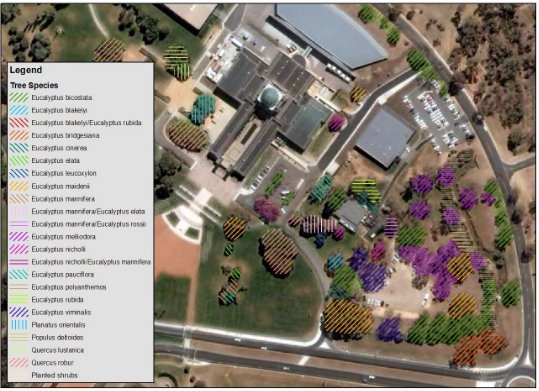

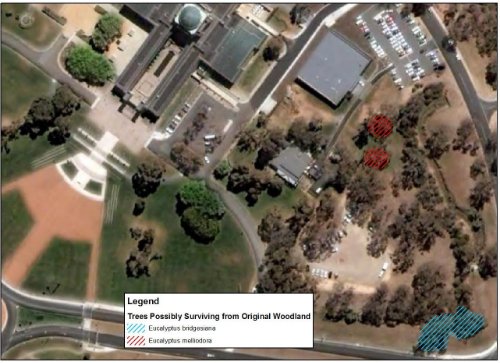

AWM Vegetation Study, Neil Urwin—Griffin Associates Environmental

Appendix I

Navin Officer, Australian War Memorial, Campbell and Mitchell, ACT—Indigenous Cultural Heritage Assessment, March 2008

Appendix J

Memorial Stakeholder and Community Consultation

Appendix K

EPBC Referral 2019-8574 Approval Conditions

Appendix K

EPBC Referral 2019-8574 Approval Conditions

Executive Summary

War memorials are ubiquitous expressions of Australian nationhood. They appear amongst every concentration of people across the country, from our cities to our tiny outback towns. But the grandest of these expressions, the monument that strives to honour all forms of remembrance and all events that need to be remembered, is the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra.

The AWM is Australia’s National Shrine to those Australians who lost their lives and suffered as a result of war. It is an important place to the Australian community as a whole and has special associations with veterans and their families and descendants of those who fought in wars for Australia.

The AWM is unique in Australia and believed rare in the world as a purpose built repository where the nature of commemoration is based in equal parts in the relationship between the building, the collections of objects and records and the commemorative spaces.

Its physical presence alone is a dominant feature of the nation’s capital: an Art Deco edifice at the head of Anzac Parade facing the federal houses of parliament across Lake Burley Griffin.

A shrine, a museum, an archive, a formal landscape and an outstanding collection of buildings, the AWM offers itself to the nation as a place for reflection, research, education and ceremony. It embodies many heritage values which are recognised by its inclusion in the National Heritage List along with Anzac Parade, the Commonwealth Heritage List, the Register of the National Estate, the ACT Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ National Heritage List and Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture, the ACT National Trust Register.

The Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and its accompanying regulations (EPBC Regulations) oblige government agencies to conserve and manage the heritage values of sites in their control. The legislation defines heritage principles that agencies must follow and directs agencies to create documents for guiding their care of heritage places, including this Heritage Management Plan.

This Heritage Management Plan (HMP) acts as a practical guide for conserving, managing and interpreting the site’s heritage. It begins by describing the AWM in detail: its history, its features and its heritage values. It discusses factors that need to be considered when managing the site, such as its statutory context and compliance requirements. The final sections of the plan provide conservation policies for the place’s managers and staff to follow. The report includes a collection of appendices that give further guidance and detailed information for asset managers and curators alike.

To conserve the AWM’s heritage values, the heritage legislation, a range of organisations and the general public, other management documents, logistics, forward planning and changing cultural attitudes need to be considered. This HMP acknowledges the significant obligations they place on the site’s managers and emphasises the need for community involvement and great care in any future development of the AWM.

Mindful of these issues, this plan provides useful policies to guide the Memorial to care for the site’s heritage values from day to day. Section 6.2 outlines general policies for the whole site and Section 6.3 focuses on individual parts in more detail. The policies cover conservation processes; management processes; stakeholder consultation and community involvement; interpretation; documentation, monitoring and review; and use, access and security. Recommended actions and timing for implementation are provided for each policy.

To put these policies into practice, the Memorial will formally adopt this HMP. Specific policies and actions will need to be implemented by the head of Buildings and Services and other sections will have roles to play as well.

The HMP offers various tools to guide policy implementation. Along with the recommended actions mentioned above these tools include an outline of a decision-making process and a works assessment for to help assess the heritage impacts of proposed actions at the site (provided as Appendices A and B).

This HMP relates to the AWM at the time of drafting (September 2018—June 2021). The information and policies in this document therefore reflect the status and condition of the AWM at this time. As the AWM undergoes changes associated with scheduled upcoming development, this program of works will be managed in accordance with the conditions of the project’s regulatory approvals and this HMP, where applicable. Updates to the topics in this HMP which reflect the outcomes of the development project will be implemented in the next version of the HMP.

The HMP confirms that the following key principles are essential to protect the national heritage significance of this important site:

- When considering change or development at the site, consult widely.

- Always be consistent with the HMP when taking any action that will affect features with heritage value.

- Integrate the HMP with the Memorial’s daily asset management and curatorial practices.

- Constantly monitor the implementation of this document and the condition of the site’s heritage values.

- In accordance with the EPBC Act provisions, review this plan after major changes in circumstance, including the completion of the AWM development project, or every five years, whichever is earlier.

Abbreviations and Definitions

Abbreviations

The following table outlines a range of standard abbreviations used in the preparation of heritage management plans as well as specific abbreviations for this report.

Abbreviation | Definition |

ACT | Australian Capital Territory |

AHC | Australian Heritage Council |

AHDB | Australian Heritage Database |

AIA | Australian Institute of Architects |

AR | Archival Recording, or Record |

AWM | Australian War Memorial |

BCA | Building Code of Australia |

BS | Buildings and Services |

BSS | Buildings and Services Section |

CAM | Communications and Marketing |

CHL | Commonwealth Heritage List |

CMG | Corporate Management Group |

CMP | Conservation Management Plan |

Cth | Commonwealth |

DAWE | Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

DCP | Development Control Plan |

DEX | Digital Experience |

EPBC Act | Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) |

FCAC | Federal Capital Advisory Committee |

GML | GML Heritage Pty Ltd |

HA | Heritage Assessment |

HIA | Heritage Impact Assessment |

HMP | Heritage Management Plan |

ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

ILO | Indigenous Liaison Officer |

LGA | Local Government Area |

MNES | Matter of National Environmental Significance |

NC Act | Nature Conservation Act 2014 (ACT) |

NAA | National Archives of Australia |

NCA | National Capital Authority |

NCP | National Capital Plan |

NFSA | National Film and Sound Archive |

Abbreviation | Definition |

NGA | National Gallery of Australia |

NHL | National Heritage List |

NLA | National Library of Australia |

NMA | National Museum of Australia |

OPH | Old Parliament House |

PO | Project Officer |

PR | Photographic Recording |

RAO | Representative Aboriginal Organisation |

RNE | Register of the National Estate |

RSSILA | Returned Sailors & Soldiers Imperial League of Australia |

Australian War Memorial Terms

To assist with understanding the references provided in this report, the Australian War Memorial terms used have been defined below.

Term | Definition |

Australian War Memorial (AWM) | Refers to the buildings (including the main Memorial building, ANZAC Hall, Administration building, the CEW Bean Building and Poppy’s Café), and surrounding grounds located at Campbell, ACT, that are managed by the Memorial (see above) as a national shrine, museum and archive. |

AWM Mitchell Precinct | Refers to the buildings located at Mitchell, ACT, that are managed by the Memorial. It includes Treloar A (also known as the Annex), Treloar B, Treloar C, Treloar D (the Old Post Office), Treloar E and Treloar F (currently under lease). |

The Memorial | Refers to the organisational body and its people that manages the AWM and the AWM Mitchell Precinct (see above). |

Main Memorial Building | Refers to the sandstone building located at the AWM. |

Definitions and Terminology

Term | Definition |

Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL) | The CHL is a list of heritage places which are within a Commonwealth area (land owned or leased by the Commonwealth) which have been identified as having one or more Commonwealth Heritage values. To have Commonwealth Heritage values a place must have been assessed as being significant against one or more of the nine Commonwealth Heritage criteria. Places in the list can have natural, Indigenous and/or historic heritage values, or a combination of these, and range from places of local through to world heritage levels of importance. |

Commonwealth Heritage criteria | Under s 341D of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act), these are the criteria prescribed in the EPBC Regulations at reg 10.03A to establish if a place within a Commonwealth area has significant heritage value for its natural, Indigenous or historic heritage values. |

Commonwealth Heritage values | Commonwealth Heritage values are the legally listed values for which a place is included in the CHL. These can comprise one or more natural and cultural (historic or Indigenous) aspects such as significance for reasons of historical, research, aesthetic or social importance, or due to a place’s significant rarity, creative or technical achievement, characteristic features of a class of place, association with important people or importance as part of Indigenous tradition. |

Term | Definition |

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) | The EPBC Act is the key piece of Commonwealth environmental legislation in Australia. It provides a legal framework to protect and manage nationally and internationally important flora, fauna, ecological communities and heritage places. The Act defines and protects these ‘matters of national environmental significance’ (MNES) as: - world heritage properties

- national heritage places

- wetlands of international importance (listed under the Ramsar Convention)

- listed threatened species and ecological communities

- migratory species protected under international agreements

- Commonwealth marine areas

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

- nuclear actions (including uranium mines)

- a water resource, in relation to coal seam gas development and large coal mining development.

The EPBC Act also regulates actions on, or impacting on, the environment on Commonwealth land, or actions by Commonwealth agencies impacting the environment in general. This includes protecting heritage values on Commonwealth land and controlling actions taken by the Commonwealth that may have a significant impact on the environment, including heritage values. |

Heritage Assessment (HA) | A HA is a report that includes the history and physical description of the property, along with analysis of environmental history and archaeological potential. Comparison with similar sites with identified heritage values is included. Historical themes using the Australian Historical Themes Framework are identified, where relevant. Assessment of this information against the criteria for the NHL and CHL is included, and a summary statement of heritage significance is provided. |

Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) | A HIA is a report that analyses the potential impacts of a proposal on the heritage values of a place. The HIA also identifies mitigation and management measures to reduce the severity of impacts, where possible. Mitigation measures can include retention and re-use of building fabric on site, interpretation of heritage values, archival recording, undertaking oral history interviews and preparing a publication on the history and heritage values of the site. Key inputs to a HIA include the alternatives considered in the planning process for the proposal. A HIA can include a HA where this has not been prepared to date. A HIA assists with deciding if a proposal needs to be referred under the EPBC Act. HIAs need to be prepared using the EPBC ACT Significant Impact Guidelines 1.1 and 1.2. For more information on these refer to the ‘Useful Guides’ section below. |

Heritage Management Plan (HMP) | HMPs are prepared for places included in the NHL, CHL, or places with identified heritage values established through a heritage assessment against the Commonwealth or National Heritage criteria. They are intended to help managers to conserve and protect the National and Commonwealth Heritage values of a place by setting out the conservation policies to be followed. HMPs need to be prepared in accordance with the requirements of the EPBC Regulations, including the National and Commonwealth Heritage management principles. HMPs include the HA (either integrated or as an appendix) and provide heritage compliance guidance, assess risks to heritage values, and provide detailed policies and guidelines to support the conservation management of the property’s identified heritage values. A maintenance guide and action plan can also be included to assist with implementing the HMP. |

Heritage Register | This is a database of heritage places or assets managed by the Memorial, and is a requirement under s 341ZB of the EPBC Act. |

Heritage Strategy | This is a document that provides for the integration of heritage conservation and management within the Memorial’s overall property planning and management framework and is a requirement under s 341ZA of EPBC Act. |

Identified heritage values | Identified heritage values refers to those values that have been identified through a heritage assessment, tested and found to meet the applicable threshold but have not been nominated or officially listed. |

National Heritage List (NHL) | The NHL is a list of heritage places which have been identified as having one or more National Heritage values. To have National Heritage values a place must have been assessed as of outstanding heritage value to the nation against one or more of the nine National Heritage criteria. Places in the lists can have natural, Indigenous and/or historic heritage values, or a combination of these. |

Term | Definition |

National Heritage criteria | Under s 324D of the EPBC Act, these are the criteria prescribed in the EPBC Regulations at reg 10.01A to establish if a place has outstanding heritage value to the nation for its natural, Indigenous or historic heritage values. |

National Heritage values | National Heritage values are the legally listed values for which a place is included in the NHL. These can comprise one or more natural or cultural (historic or Indigenous) aspects such as significance for reasons of historical, research, aesthetic or social importance, or due to a place’s significant rarity, creative or technical achievement, characteristic features of a class of place, association with important people or importance as part of Indigenous tradition. |

Throughout this HMP, the terms place, cultural significance, fabric, conservation, maintenance, preservation, restoration, reconstruction, adaptation, use, compatible use, setting, related place, related object, associations, meanings, and interpretation are used as defined in The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, 2013 (the Burra Charter). Therefore, the meanings of these terms in this report may differ from their popular meanings.

Term | Definition |

Place | Site, area, land, landscape, building or other work, group of buildings or other works, and may include components, contents, spaces and views. |

Cultural significance | Aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations. Cultural significance is embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects. Places may have a range of values for different individuals or groups. |

Fabric | All the physical material of the place including components, fixtures, contents, and objects. |

Conservation | All the processes of looking after a place so as to retain its cultural significance. |

Maintenance | The continuous protective care of the fabric and setting of a place, and is to be distinguished from repair. Repair involves restoration or reconstruction. |

Preservation | Maintaining the fabric of a place in its existing state and retarding deterioration. |

Restoration | Returning the existing fabric of a place to a known earlier state by removing accretions or by reassembling existing components without the introduction of new material. |

Reconstruction | Returning a place to a known earlier state, which is distinguished from restoration by the introduction of new material into the fabric. |

Adaptation | Modifying a place to suit the existing use or a proposed use. |

Use | The functions of a place, as well as the activities and practices that may occur at the place. |

Compatible use | A use which respects the cultural significance of a place. Such a use involves no, or minimal, impact on cultural significance. |

Setting | The area around a place, which may include the visual catchment. |

Related place | A place that contributes to the cultural significance of another place. |

Related object | An object that contributes to the cultural significance of a place but is not at the place. |

Associations | The special connections that exist between people and a place. |

Meanings | Denote what a place signifies, indicates, evokes or expresses. |

Interpretation | All the ways of presenting the cultural significance of a place. |

In addition to the Burra Charter terms, the following have specific meanings within the context of this report:

Term | Definition |

Attribute | A feature that embodies the heritage values of a place. |

Element/Component | A part of an attribute, or individual spaces within a place. |

Authenticity | This is a measure of the place as an authentic product of its history and of historical processes. Cultural heritage places may meet the conditions of authenticity if their cultural values are faithfully and credibly expressed through a variety of attributes such as form and design, materials and substance, traditions, techniques and management systems, location and setting, language and other forms of intangible heritage, spirit and feeling. |

Integrity | This is a measure of the wholeness and intactness of the place and its attributes. Examining the conditions of integrity requires assessing the extent to which the place: - includes all attributes and elements necessary to express its value;

- is of adequate size to ensure the complete representation of the features and processes that convey the place’s significance; and

- suffers from adverse effects of development and/or neglect.

|

Policy (Conservation Policy) | A statement or suite of statements framed to guide the ongoing use, care and management of the place and to retain, and if possible reinforce, its cultural significance. Once adopted or endorsed, they should be implemented or acted upon. |

Guideline | A statement framed to clarify or guide the implementation of a broader conservation policy, setting a preferred direction for such implementation. |

1.0

Introduction

1.1 Background

The AWM is a national shrine, a museum and an archive located in the northern Canberra suburb of Campbell in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). It is managed by the Memorial and is a major research centre and tourist attraction, now consistently attracting more than one million visitors per year.1

These functions of the AWM are supported by the AWM Mitchell Precinct, which is also managed by the Memorial. The AWM Mitchell Precinct, consisting of Treloar A (also known as Annex A), Treloar B, Treloar C, Treloar D (the Old Post Office), Treloar E and Treloar F (currently under lease), provides additional storage and conservation facilities for the AWM collection in the suburb of Mitchell, ACT.

The values of the AWM are recognised through its inclusion in the National Heritage List (NHL) and the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL) (refer to Appendix E and F for the official citations). The EPBC Act requires that a HMP be prepared for National and Commonwealth Heritage places to conserve, present and transmit their heritage values.

This HMP has been prepared by GML Heritage Pty Ltd (GML) in line with the requirements of the EPBC Act and its Regulations. A compliance table showing how this HMP meets the requirements of the EPBC Act and its Regulations is included at Appendix C. Additional text has been provided by the Memorial, in particular on the Australian War Memorial Development Project 2019–2028, provided 27 November 2021, at Sections 2.5, 5 and 6.

1.2 Previous Heritage and Conservation Management Plans

This HMP will update and replace the previous management plans for the AWM, which are listed as follows:

- Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd 2011, Australian War Memorial Heritage Management Plan, prepared for the Australian War Memorial, Canberra;

- Pearson, M and Crocket, G 1995, Australian War Memorial Conservation Management Plan (CMP), prepared for Bligh Voller Architects (referred to as the 1995 CMP);

- Crocket, G 1997, Australian War Memorial Significance Assessment Report, prepared for Bligh Voller Architects; and

- Bligh Voller Nield and HMC 1997, Australian War Memorial Heritage Conservation Masterplan, prepared for the Australian War Memorial.

The 1995 CMP was based on the Register of the National Estate (RNE) listing (date of listing 21 October 1980, Place ID 13286). Entry in the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL) occurred in 2004 while entry in the National Heritage List (NHL) occurred in 2006.

The Memorial has also produced a Heritage Strategy and Heritage Register to meet and manage its heritage obligations under the EPBC Act and its Regulations. The heritage values of the AWM Mitchell Precinct have been assessed in the AWM Heritage Register.

1.3 Location of the Site

The AWM is located in the ACT suburb of Campbell and is bounded by Limestone Avenue to the southwest, Fairbairn Avenue to the southeast and Treloar Crescent to the north. It is sited in a crucial symbolic location at the terminus of the land axis of Walter Burley Griffin’s plan for Canberra (refer to Figure 1.1).

The AWM has an area of approximately 14 hectares, including the whole of Section 39, Campbell, and is located at the foot of Mount Ainslie. This boundary is the area of land owned and controlled by the Memorial and is also the boundary of the Commonwealth Heritage listing for the AWM (refer to Section 1.4).

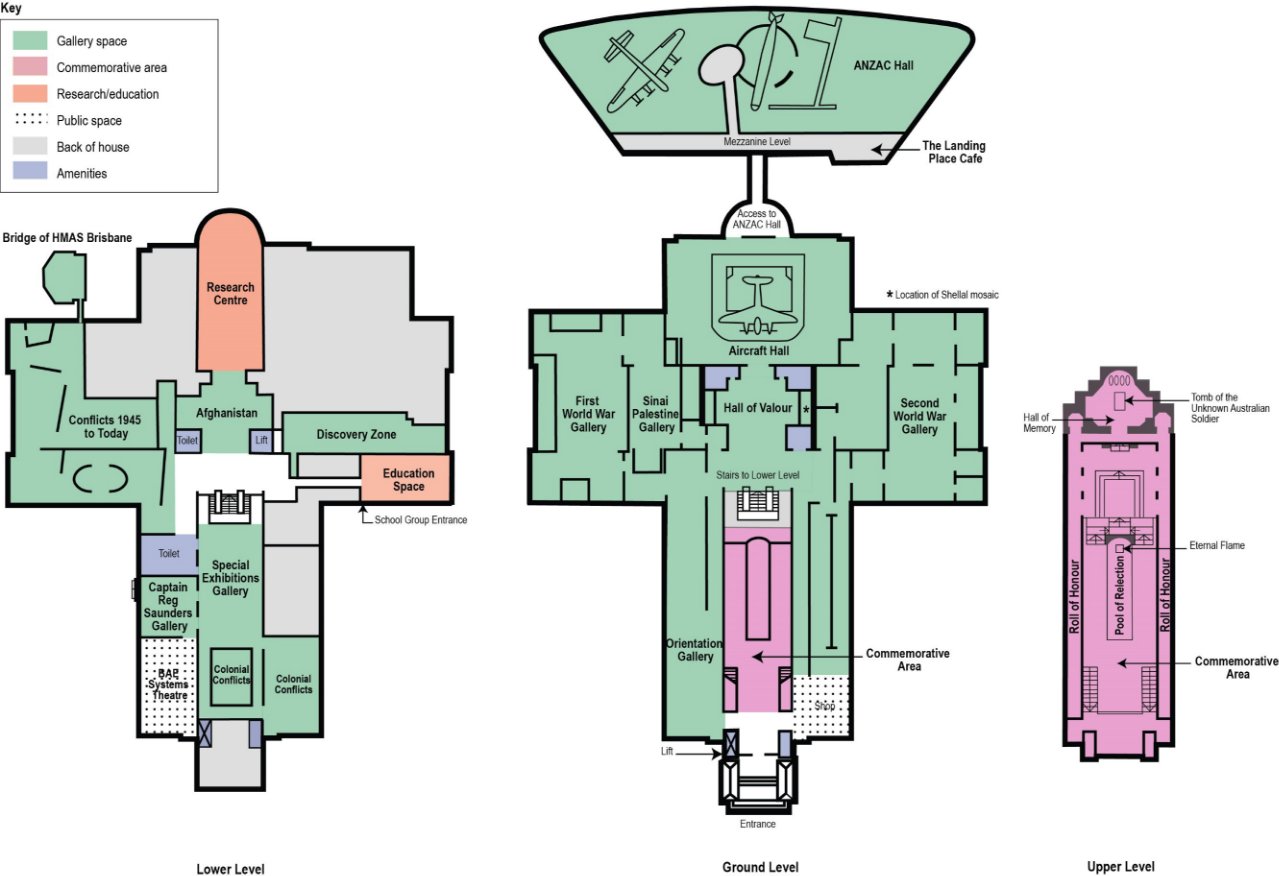

The AWM comprises:

- the main Memorial Building;

- the Administration Building;

- landscaped grounds incorporating sculptures, memorials, large technology objects, plaques, the Parade Ground and commemorative and landscape plantings (refer to Figure 1.2).

During the drafting this plan (September 2018–June 2021) the Memorial has scheduled the commencement of a development project at the AWM Campbell site. The development includes the removal and replacement of Anzac Hall, creation of a glazed link connecting the main Memorial Building and the new Anzac Hall, and a new Research Centre. These elements will be located in, and around, the main Memorial Building. This project has been approved under the EPBC Act, and the Memorial will manage the project in accordance with the conditions of this approval; this includes management of the project under the previous Heritage Management Plan (2011) under which the proposal was developed, submitted and approved.

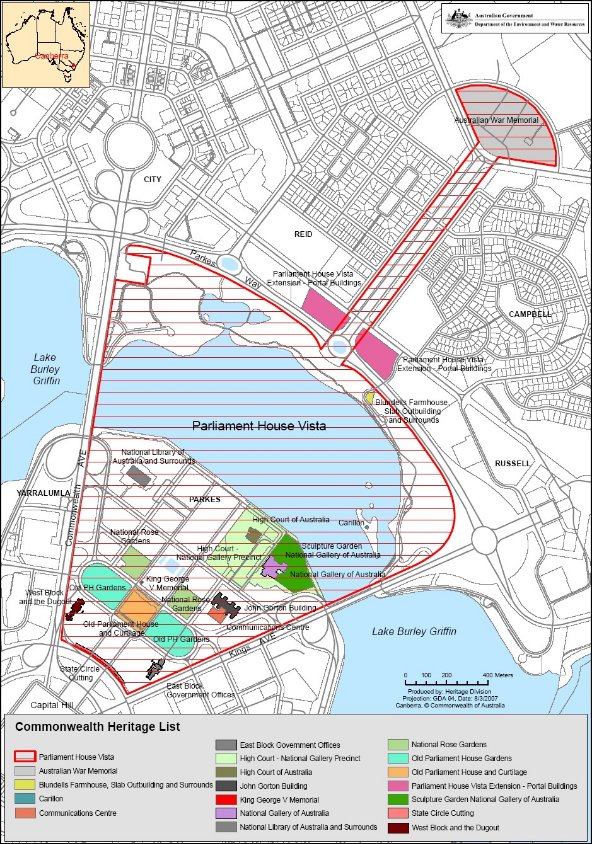

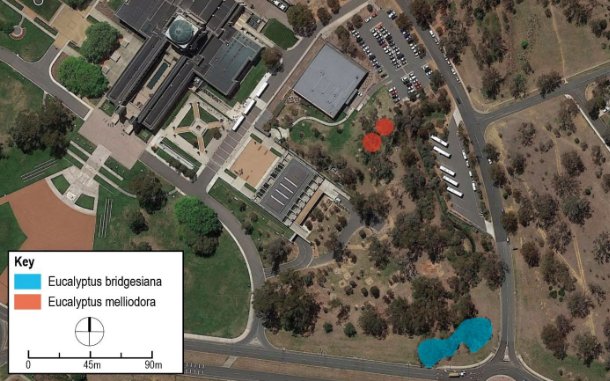

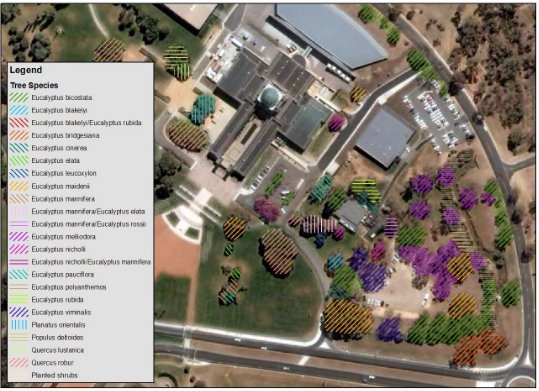

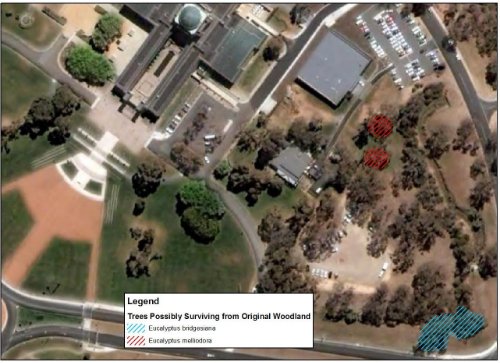

Figure 1.1 The location of the AWM (red outline) within the context of the central national area of Canberra and the National Triangle (dotted orange outline). (Source: Google Earth with GML overlay, 2018)

1.4 Heritage Listings

The AWM is entered in the CHL and the listing boundary is shown in Figure 1.2. The CHL citation is included in Appendix E.

The AWM is also entered in the NHL. The National Heritage listing incorporates the whole of Anzac Parade (including the median strip and its monuments) and the AWM, shown in Figure 1.3. The complete NHL citation is included in Appendix F. The area of the National Heritage listing is approximately 25 hectares, with Anzac Parade owned and controlled by the National Capital Authority (NCA), not the Memorial. This HMP does not cover the Anzac Parade portion of the National Heritage place, which has its own HMP.2

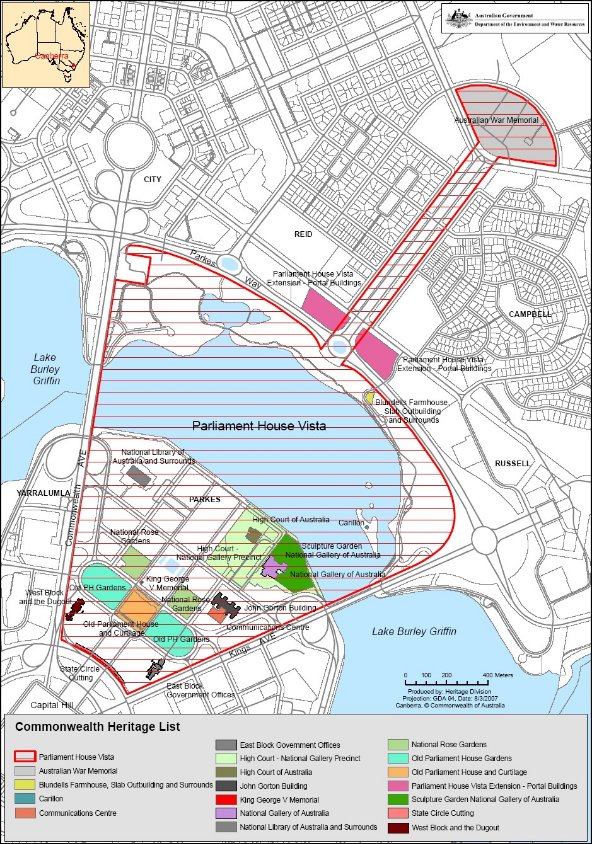

The AWM also falls within the Parliament House Vista (see Figure 1.4), another Commonwealth Heritage place. The complete CHL citation is included in Appendix F.

Table 1.1 Summary of Statutory Heritage Listings Relevant to the AWM.

Place | Location | Class | Status | Place Number |

National Heritage List |

Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade | Anzac Parade, Campbell, ACT | Historic | Listed Place | 105889 |

Commonwealth Heritage List |

Australian War Memorial | Anzac Parade, Campbell, ACT | Historic | Listed Place | 105469 |

Parliament House Vista | Anzac Parade, Parkes, ACT | Historic | Listed Place | 105466 |

Figure 1.2 The AWM, showing the CHL boundary in red. (Source: Google Earth with GML overlay, 2018)

Figure 1.3 The NHL boundary shown outlined in yellow, incorporating both the AWM and Anzac Parade, with the CHL boundary of the AWM outlined in red. (Source: Google Earth with GML overlay, 2018)

Figure 1.4 The Parliament House Vista Commonwealth Heritage boundary outlined and hatched in red, showing places of heritage significance within the vista. (Source: Department of the Environment and Water Resources, 2008)

1.5 Heritage Register

The Memorial has prepared a Heritage Register in accordance with Section 341ZB(1)(c) of the EPBC Act and has assessed the heritage values of each place it owns and controls. The Heritage Register is a separate document that was created by GML for the Memorial in August 2020.

The AWM has eight entries in the Heritage Register, as set out in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Places Owned and Controlled by the Memorial with Commonwealth and National Heritage Value.

Location | Element of Place | Register Entry Number | CHL/NHL Status |

AWM | Entire AWM site | CH100 | CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Hall of Memory, Courtyard and Roll of Honour | CH101 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Galleries | CH102 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Dioramas | CH102.001 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Landscape | CH103 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Lone Pine | CH103.001 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Sculpture Garden | CH103.003 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

Aboriginal site | CH103.004 | Within CHL Place ID 105469 Within NHL Place ID 105889 |

AWM Mitchell Precinct | Treloar A (also known as Annex A) | CH104 | Not listed. Identified Commonwealth Heritage values |

1.6 Consultation

GML consulted with the Building and Services Section within the AWM Corporate Services Branch throughout the preparation of the HMP.

Consultation with relevant Indigenous community members was undertaken in the preparation of this HMP in 2018. This consultation was undertaken in accordance with the Ask First Guidelines.3 In the ACT there are four Representative Aboriginal Organisations (RAOs) with whom consultation should be undertaken for heritage related projects. These RAOs are:

- Buru Ngunawal Aboriginal Corporation;

- Mirrabei (formerly known as Little Gudgenby River Tribal Council); and

Consultation discussion was held on site with Wally Bell of the Buru Ngunawal Aboriginal Corporation. All four groups were invited to participate in the consultation on site. A summary of the consultation is in included in Section 3.2.11 of this report.

1.7 Endnotes

1 Australian War Memorial 2017, Australian War Memorial Corporate Plan, 2017-2021, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, p 5.

2 Geoff Butler & Associates et al., Anzac Parade, Canberra—Heritage Management Plan, report prepared for National Capital Authority, August 2013.

3 Australian Heritage Commission 2002, Ask First: A Guide to Respecting Indigenous Heritage Places and Values, Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra.

2.0

Understanding the Place—Historical Context

This section provides a summary of the history of both the AWM as a place and the Memorial as an organisation. It draws on the historical analysis presented in the 1995 CMP1 and 2011 HMP, supplemented with additional material relating to the recent history of the place.

Further historical information regarding individual elements within the AWM is provided in the Heritage Register.

2.1 Aboriginal Cultural and Historical Context

Tribal boundaries within Australia are largely based on linguistic evidence and it is probable that boundaries, clan estates and band ranges were fluid and varied over time. Consequently, ‘tribal boundaries’ as delineated today must be regarded as approximations only and relative to the period of, or immediately before, European contact. Social interaction across these language boundaries appears to have been a common occurrence.

According to Tindale,2 the territories of the Ngunawal, Ngarigo and the Walgalu peoples coincide and meet in the Queanbeyan area. The AWM probably falls within the tribal boundaries of the Ngunawal people.

References to the traditional Aboriginal inhabitants of the Canberra region are rare and often difficult to interpret.3 However, the consistent impression is one of rapid depopulation and a desperate disintegration of a traditional way of life over little more than 50 years from initial European contact.4 This process was probably accelerated by the impact of European diseases, which may have included the smallpox epidemic in 1830, influenza, and a severe measles epidemic by the 1860s.5

By the 1850s the traditional Aboriginal economy had largely been replaced by an economy based on European commodities and supply points. Reduced population, isolation from the most productive grasslands, and the destruction of traditional social networks meant that the final decades of the region’s semi-traditional Indigenous culture and economy was centred around European settlements and properties.6

By 1856 the local ‘Canberra Tribe’, presumably members of the Ngunawal, were reported to number around 707 and by 1872 only five or six ‘survivors’ were recorded.8 In 1873, one so-called ‘pure blood’ member remained, known to the European community as Nelly Hamilton or ‘Queen Nellie’.

Combined with other ethnohistorical evidence, this lack of early accounts of Aboriginal people led Flood 9 to suggest that the Aboriginal population density in the Canberra region and Southern Uplands was generally quite low.

Frequently, only so called ‘pure blooded’ individuals were considered ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘tribal’ by European observers. This consideration made possible the assertion of local tribal ‘extinctions’. In reality, ‘Koori’ and tribal identity remained integral to the descendants of the nineteenth-century Ngunawal people, some of whom continue to live in the Canberra/Queanbeyan/Yass region.

2.2 Origins and Establishment

The origins of the AWM are integrally associated with CEW Bean, Australia’s official war correspondent during World War I (refer to Figure 2.1). Bean envisioned a national war museum in Australia’s new capital, Canberra, which would house the relics and trophies of battle. At the same time, Bean was actively working towards earning Australia the right to keep and maintain its own war

records, following the success of Canada in this regard in 1916. In May 1917, Lieutenant John Treloar was appointed officer-in-charge of the Australian War Records Section, before serving as Director of the Memorial between 1920 and 1952 (refer to Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.1 CEW Bean, war correspondent and historian who worked towards the founding of an Australian war museum, 1919. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number P04340.004)

Figure 2.2 John Treloar, Officer-in-Charge of Australian War Records, and Director of the AWM for 32 years. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 023405)

Earlier in 1917 the Commonwealth had indicated support for Bean’s concept of a national war museum in Canberra and by 1918 Bean had strengthened his vision to link the collected war relics and war records with the idea of a lasting memorial to those who had died in the war. An Australian War Museum committee was established in 1919 and Henry Gullett was appointed first Director of the Museum. Bean and Treloar believed that the memorial and museum functions were philosophically and operationally inseparable and, along with Gullett, they were to guide its creation and operation over a 40-year period.

The existing site of the AWM may have been considered by Bean as early as 1919. Charles Daley, Secretary of the Federal Capital Advisory Committee, claims to have suggested the site where Walter Burley Griffin had located his ‘Casino’—at the terminal of the main land axis of the city plan. In 1923, the Commonwealth finally announced its intention to proceed with this site for the ‘Australian War Memorial’ and in 1925 the AWM was constituted in Commonwealth legislation. The AWM was inaugurated on 25 April 1929 (refer to Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 The inauguration of the AWM on Anzac Day 1929. (Source: National Archives of Australia, 3560, 5253)

The competition for the design of the AWM was conducted from 1925–1926. However, none of the entries met all of the competition’s conditions and no winner was announced. Two of the competitors, Emil Sodersten (formerly Sodersteen) and John Crust, were subsequently asked to develop a new collaborative design incorporating the architectural style of Sodersteen and the innovative and cost- cutting approach of Crust. The new joint Sodersteen and Crust design was presented in 1927. The architectural style of the design was primarily Sodersteen’s work and drew upon the then recent development of the Art Deco style from Europe. This architectural styling became popular in Canberra in the postwar period, influencing buildings such as the Institute of Anatomy (now the National Film and Sound Archive) built in 1928–1930. The form of the AWM and design of the main Memorial building was also strongly influenced by Crust’s intention to incorporate a commemorative courtyard for the Roll of Honour, along with CEW Bean’s original concept for a central ‘great hall’, now the Hall of Memory.

Construction at the AWM, which began in 1928–1929, was curtailed and then postponed by the onset of the Depression. In 1934, the ‘Lone Pine’ propagated from seed brought back from the battlefield of Gallipoli was planted within the otherwise denuded landscape (refer to Figure 2.4). Some construction work started again but many details of the building remained unresolved. While the main Memorial building is one of Australia’s earliest major buildings designed and constructed in the Art Deco style, the design was subject to a host of changes and the details of the building were not finally settled until 1936.

Figure 2.4 The Duke of Gloucester planting the Lone Pine, 1933. (Source: National Library of Australia, P583, Album 827)

In 1937 the Memorial’s Board resolved to commission sculpture, stained glass windows and mosaics to complete the Hall of Memory. Napier Waller, a noted Australian artist in large scale murals and mosaics, was invited to submit designs for both the mosaic and stained glass. Leslie Bowles was commissioned to produce designs for the large scale sculpture. Both artists had served in the armed forces in World War I. During World War II, the interiors of the Hall of Memory were reconsidered, and Percy Meldrum collaborated with the artists to help solve the architectural issues of the applied decoration. While Waller was able to proceed with his designs for mosaics, Bowles’ models were rejected. Ray Ewers continued Bowles’ work, with the design for the ‘Australian servicemen’ being accepted in 1955. The installation of the mosaics also commenced in 1955, under the supervision of Aldo Rossi and Severino de Marco (refer to Figure 2.5). The Hall of Memory was finally opened in 1959 (refer to Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.5 Aldo Rossi, Severino de Marco and Mr Napier Waller examining mosaic prior to fixing, 1955. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 042349)

Figure 2.6 Aldo Rossi putting the finishing touches to the dome in 1958. (Source: National Archives of Australia, A1200/18)

Parts of the main Memorial building were occupied by AWM staff and collections as early as 1935, although the main structure was not completed until 1941 (Figure 2.7–Figure 2.8). The official opening on 11 November 1941, Remembrance Day, acknowledged that the building was substantially complete, however, some areas were not finished until many years later.

Figure 2.7 The main Memorial building during construction in 1941. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number P0131.002)

Figure 2.8 The main Memorial building prior to completion of the Parade Ground and landscaping. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number P01313.002)

Figure 2.9 The cloisters in 1945 before the initial installation of the Roll of Honour. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 085709)

One of the outcomes of the long construction period was the evolution of enhanced display technology for the collection. Another was the advent of World War II. In 1939, the intended role of the AWM—to commemorate those who died in World War I, then known as the Great War—was reviewed. After much consideration, the Board of the Memorial recommended in 1941 that the scope of the Australian War Memorial Act be extended to incorporate the new war and Treloar transferred to the Department of Information as the Head of Military History Section at Army Headquarters to coordinate the collection of relics and records arising from that conflict. As a result, plans for the extension of the main Memorial building were prepared c1947, although not constructed until the 1960s. The Australian War Memorial Act was again amended in 1952 to extend its scope to include Australian involvement in all wars. In 1975 the scope was further broadened to allow commemoration of Australians who died as a result of war, but who had not served in the Australian armed forces.10

2.3 Expansion and Evolution

The AWM is a place that has always adapted by responding to society’s changing need for commemoration and perceptions of the significance of military history generally. The decision to include World War II in the scope of the AWM necessitated extensions to the space available for display (refer to Figure 2.10). In 1961 the Roll of Honour panels commemorating the dead of World War I were installed within the cloisters (refer to Figure 2.9). Supplementary panels commemorating later conflicts have continued to be installed since the 1960s, with the panels updated annually to reflect those involved in ongoing conflicts. In 1968–1971 two wings were constructed to extend the transepts of the main Memorial building. These extensions were entirely in keeping with the original concept of the building, utilising the same design and stonework. The extensions of the transepts

enhanced the symmetry of the design and their scale offset the ‘Byzantinesque’ dome and reinforced the church-like cruciform plan of the building. The first ancillary building to be built was the Outpost Café, constructed in 1960 (refer to Figure 2.11).

In 1988 the Administration Building was the first significant additional structure to be added to the AWM, allowing the transfer of administrative functions from the main Memorial building.

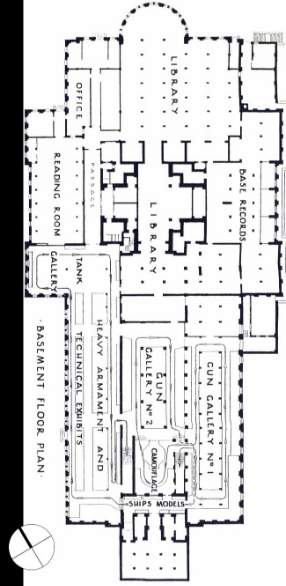

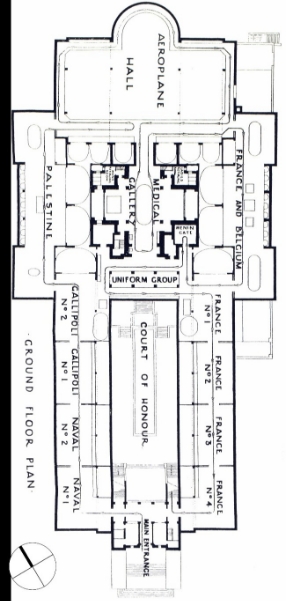

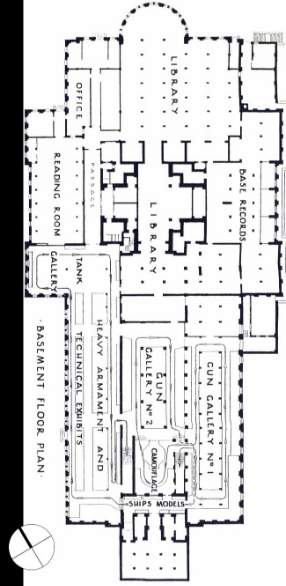

Figure 2.10 Floor plans for the original galleries prior to the construction of the additional wings in the 1960s. (Source: Australian War Memorial)

Figure 2.11 The former ‘Outpost Café’, shortly before its demolition. (Source: GML 2007)

2.4 New Meanings

The installation of the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Solider in 1993 signalled another significant evolution in the meaning of the AWM. The famous speech delivered by the then prime minister, Paul Keating, at the interment signalled that, more than ever before, the sacrifice of ordinary men and women in war was seen as crucial to national identity:11

The Unknown Australian Soldier we inter today was one of those who by his deeds proved that real nobility and grandeur belongs not to empires and nations but to the people on whom they, in the last resort, always depend.

That is surely at the heart of the Anzac story, the Australian legend which emerged from the war. It is a legend not of sweeping military victories so much as triumphs against the odds, of courage and ingenuity in adversity. It is a legend of free and independent spirits whose discipline derived less from military formalities and customs than from the bonds of mateship and the demands of necessity.

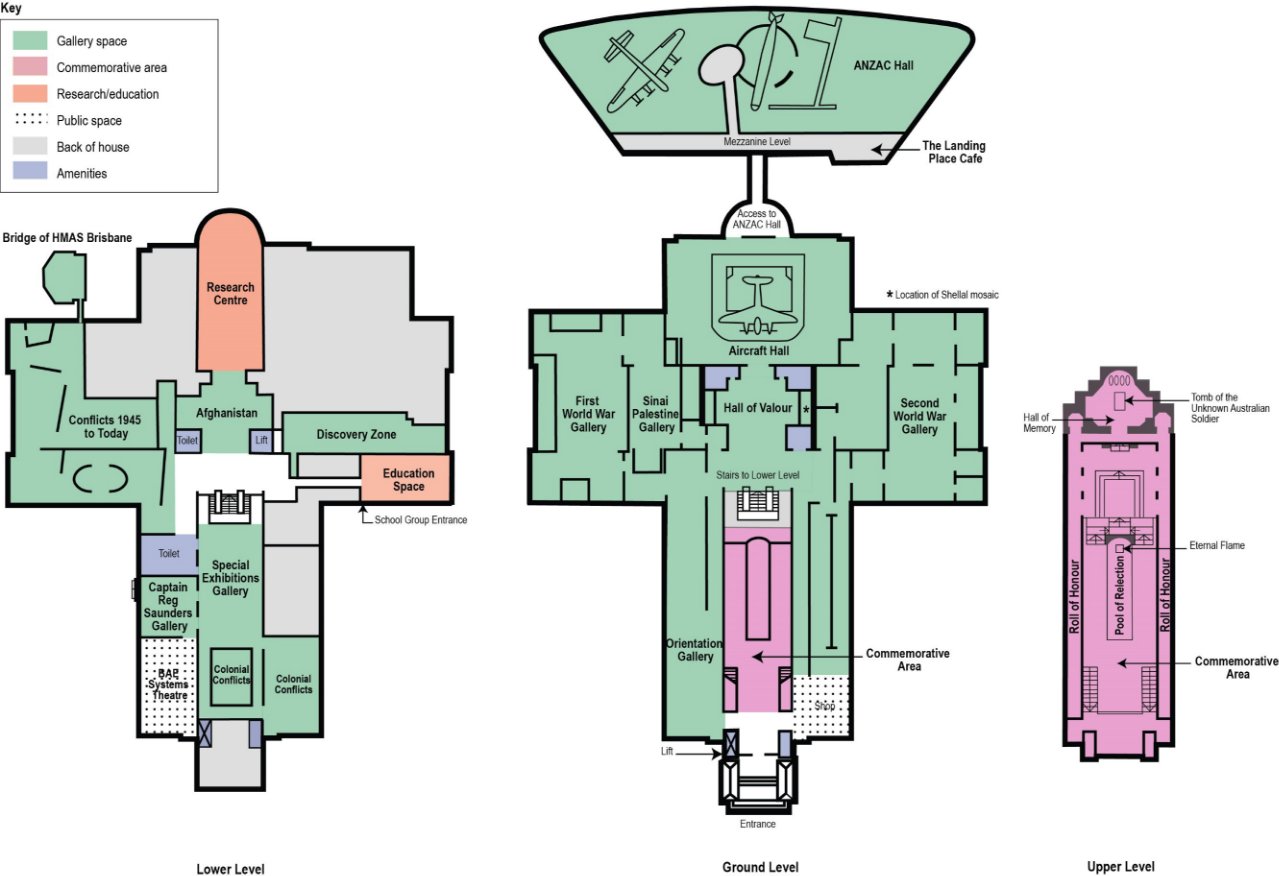

It has been suggested that with the interment of the Unknown Australian Soldier the meaning of the Hall of Memory has been clarified and entrenched as a national mausoleum and the heart of the AWM.12 With the growth of the importance of ‘heritage’ through the 1990s, memorials to war have taken on new meanings in Australian society; it has been argued that they provide a mythology or even a sacred component for the secular modern nation.13 This is reflected in a dynamic period of change and development across the AWM, mirroring the rise in the symbolic cultural importance of memorials which commemorate the sacrifice of Australians in war. From the mid-1990s to the present, the Memorial has expanded and upgraded its galleries and exhibitions and also made significant changes to its surrounding grounds. Between 1996 and 1999, the Memorial undertook Gallery Development Stage One. This included redeveloping the Second World War Galleries and Research Centre, relocating and changing the Post 1945 Galleries, the redesign and expansion of the Orientation Gallery and the creation of a temporary exhibition space. These were opened by then Prime Minister John Howard.

This period also included the final stage of development of the Western Courtyard and Sculpture Garden. The Aircraft Hall was completed shortly after. ANZAC Hall, adjoining the rear of the main Memorial building, was completed in 2001. This provided a major new exhibition space where large objects are now presented in an ‘object theatre’ manner. This building was awarded the Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Best Public Building by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) in 2005.

The subsequent stage of redevelopment, Gallery Development Two, centred around the development of the Conflicts 1945 to Today Galleries on the lower level of the main Memorial building and the new Discovery Zone, a hands-on education centre that opened in 2007. To facilitate this development, staff and some of the collection were required to relocate to a new building, constructed on the eastern side of the main Memorial building. Named after CEW Bean, the building was opened in April 2006. It is connected to the main Memorial building by a tunnel. The new offices were opened in February 2008. The Conflicts 1945 to Today galleries display collections from conflicts that Australia has been involved in since World War II, including various peacekeeping missions. They were opened by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. These galleries display major collection items, such as an Iroquois helicopter from the Vietnam War, and have also reinvigorated the Memorial’s use of dioramas by developing one based on the Battle of Kapyong during the Korean War. Nearby a ‘virtual’ electronic diorama was produced on the Battle of Maryang San. Australia’s involvement in conflicts since 1945, including Korea (1950– 1953), Vietnam (1962–1975), the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) and the Indonesian Confrontation (1962–1966) are interpreted. Also included in these galleries is a link to a display in the bridge of the HMAS Brisbane, which has been installed outside the main Memorial building. This ship saw action in the Vietnam War and the First Gulf War.

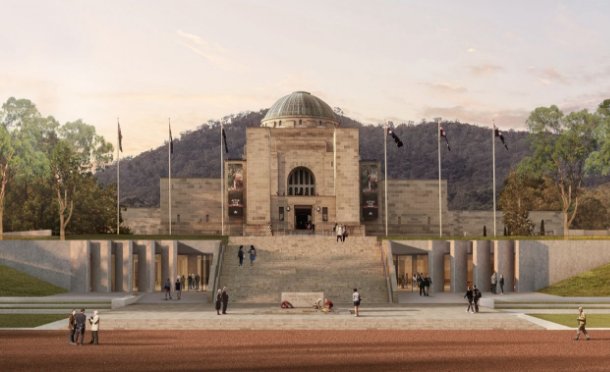

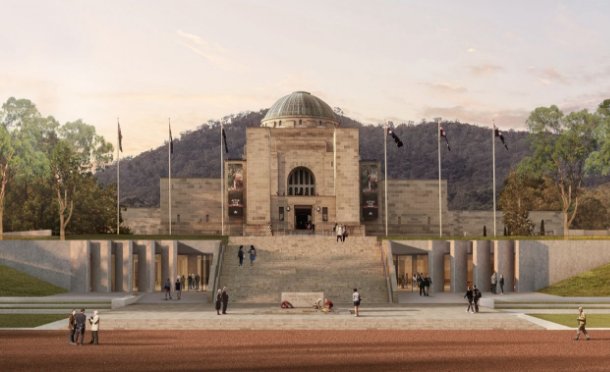

In 2004 the Parade Ground, on the southern face of the AWM, was redeveloped to improve access and comfort for spectators and dignitaries at ceremonial events. The design used the same materials as in the main Memorial building, in keeping with the national significance of this site. All of the existing terraces were demolished, leaving only the Stone of Remembrance. Sandstone terraces and a forecourt were created around the stone. The design has successfully enhanced the relationship between the AWM and Anzac Parade and is a fittingly grand, yet simple, design for this significant ceremonial area.

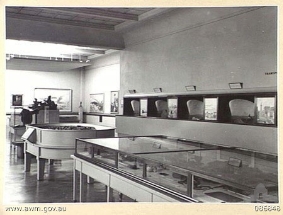

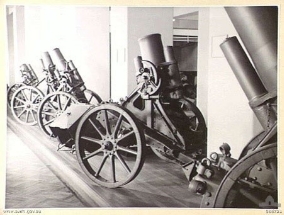

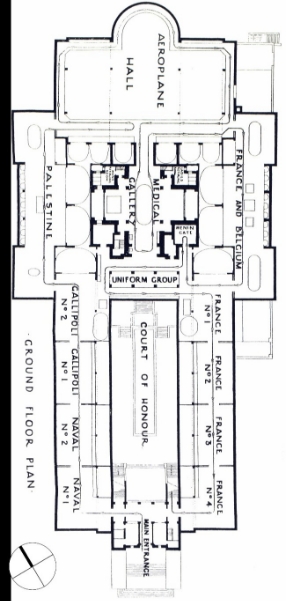

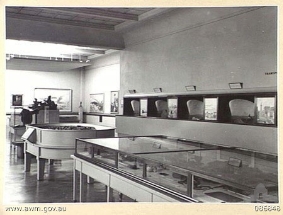

Figure 2.12 The Sinai and Palestine Gallery in 1944. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 086848) |

Figure 2.13 One of the France galleries in 1944 showing the effect of the skylights. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 086859) |

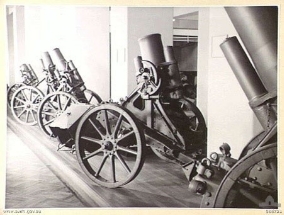

Figure 2.14 Trench mortars displayed in the Gun Gallery located on the lower level, beneath the courtyard in 1945. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number 085721) |

Figure 2.15 The Pozieres, Semakh and Magdhaba dioramas in their original location, c1947. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ID number XS0375) |

Figure 2.16 Photograph of the AWM and Anzac Parade in 1984. (Source: Canberra, from Limestone Plains to Garden City, National Capital Development Commission, p 72)

Figure 2.17 Anzac Day at the AWM, 1965. (Source: National Library of Australia, nla.obj-143720304)

2.4.1 The Western Precinct—1999 to Present

The Western Precinct of the AWM was remodelled in 1999 for the creation of the commemorative Sculpture Garden—a place to display individual memorials and a range of significant sculptures from the Memorial’s collection. In 1995, Ray Ewers’ monumental ‘Australian Serviceman’ was moved from the Hall of Memory to the Sculpture Garden and other works have subsequently been sited in the area. The sculptures have been linked with commemorative plantings, including the earliest planting on the site, the Lone Pine. Sir Betram Mackennal’s famous bust ‘Bellona’ or ‘War’ was sited near the Lone Pine in 1998. This new location is particularly appropriate because Mackennal is said to have presented the work to the Commonwealth Government as a mark of respect for the valour exhibited at Gallipoli.

Two new memorials were commissioned in 1998 (British Commonwealth Occupation Force) and 1999 (Australian Servicewomen’s memorial). These more architectural memorials contrast with the monumentality and figurative nature of the earlier bronze sculptures which have been relocated to the garden. Since this time, a total of 25 memorials or sculptures have been installed within the formalised grounds of the AWM, and 10 large objects put on display. Over 150 plaques which commemorate individual unit associations have also been located in the garden.

Western Precinct Memorials

Since 1999 a number of memorials have been installed in the Western Precinct.

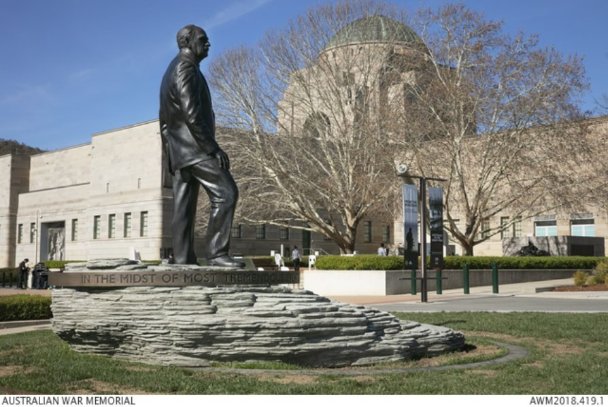

General Sir John Monash (2018)

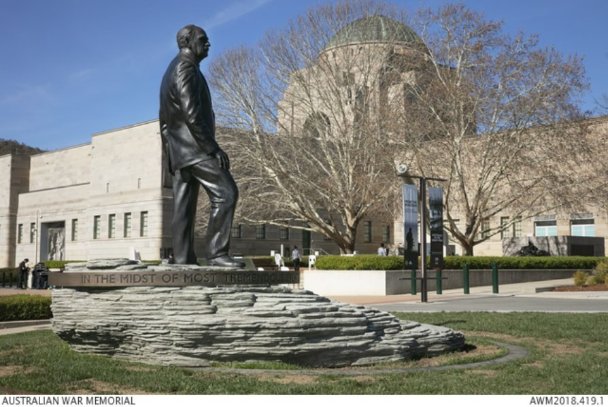

Figure 2.18 Sir John Monash sculpture, Australian War Memorial (Source: Australian War Memorial).

A sculpture of Sir John Monash was commissioned in 2016 to commemorate Sir John Monash’s legacy as an outstanding general of the First World War and his dedication to civic duty in the years after the war. It comprises of a larger than life size bronze realist figure of the older Sir John Monash clothed in a suit and displaying his military medals, gazing outward on top of a plinth cast in cement to resemble a large outcrop of striated sedimentary rock.

Monash stands with one foot placed on a rocky rise, signifying his commanding view of Australia’s destiny in its global context. The strength of his gaze and purposeful profile signifies his vision and leadership. His clothes intimate that he was a man of his time, however, the inclusion of the phrase “I am living and moving” asserts Monash’s continuing centrality to Australian cultural life, the way his legacy still lives and moves in us today. He holds a notebook in his right hand, alluding to his great intellectual legacy as a moving and humane chronicler of the war, as well as one of its greatest tacticians and leaders Symbolically, the rock functions both as a testament to Monash’s intellectual strength and fortitude, but also to the burden of responsibility that fell to him during his service and public life. The concrete plinth also gestures towards Monash’s pioneering work as an engineer in introducing reinforced concrete as a material in construction.

The modelling of the figure and fabrication of the plinth was carried out in the Visual Arts Workshops at Queensland University of Technology over a period of 4 months from October 2017. The figure and rings were cast in bronze at Billman’s Foundry, Castlemaine, Victoria in March 2018.

For Our Country (2018)

Figure 2.19 'For Our Country' sculpture (Source: Australian War Memorial).

'For our Country' recognises the military service of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is a space in which to commemorate their service in all conflicts in which Australia's military has been deployed. It is also a place to contemplate the sacrifices that Indigenous Australians have made and continue to make in defence of Country.

The idea for the commission was raised in 2016, following national consultation on the Memorial’s recognition and acknowledgement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service. Boyd and Edition Office’s design was selected from a shortlist of submissions and approved by a group of Indigenous military personnel, curators, and local Elders.

In 2018 artist Daniel Boyd, a Kudjala/Gangalu/Kuku, Yalanji/Waka, Waka/Gubbi Gubbi/Wangerriburra/ Bandjalung man from North Queensland, and Edition Office architects were commissioned to design a new sculpture for the Memorial Sculpture Gardens that recognised and commemorated the military service and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

For our Country takes the form of a sculptural pavilion that measures 11 metres wide and 3 metres high, set behind a ceremonial fire pit within a circular stone field. From the front of the pavilion visitors see a wall of two-way mirrored glass covered in thousands of transparent lenses that reflect the viewer and the Memorial.

Connection to landscape is important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. The memorial contains soil deposited from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nations across Australia. The artist intended that each Nation be commemorated in this place, where the soil of their Country joins the many lands our ancestors have defended and from which they came to serve Australia.

Flanders Field Memorial Garden (2013)

Figure 2.20 Flanders Field Memorial Garden (Source: Australian War Memorial).

The Flanders Fields Memorial Garden is set within a formal grass court in the Australian War Memorial’s Western Precinct. An adjacent bronze plaque includes a dedication listing the Australian divisions that fought in Flanders, their insignia, and the cemeteries in which their members are buried.

The Garden is a commemoration of the Great War and, in particular, the 12,000 Australian lives lost in Belgium in 1917, of whom 6,000 have no known graves and are named on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ieper.

Work on the garden began in 2013, four years after the Flemish and Australian governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding for cooperation between Australia and Belgium to increase community understanding and recognition in their respective countries of their shared history of the twentieth century's World Wars.

The commemorative text of John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders fields” is inscribed atop the Garden’s low stone walls. The overlapping text is designed to encourage visitors to experience the garden from every aspect as they walk around it in commemorative reflection. Much of the soil in the garden has come from areas of Flanders: It was collected in 2015 and 2016 with the assistance of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission from the Tyne Cot Cemetery and many of the battlefields in which Australian soldiers fell. The soil was shipped to Australia for treatment in early 2017 before being mixed with Australian soil and added to the garden. It is within this soil that the poppies will continue to grow.

The Memorial gratefully acknowledges the support of the Flemish government, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the Australian Embassy to Belgium and Luxembourg and Mission to the European Union and NATO.

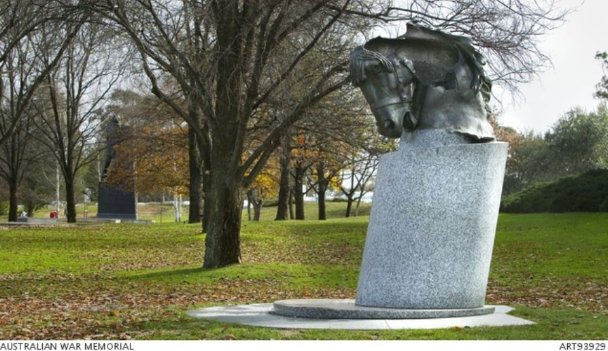

Animals in War (2009)

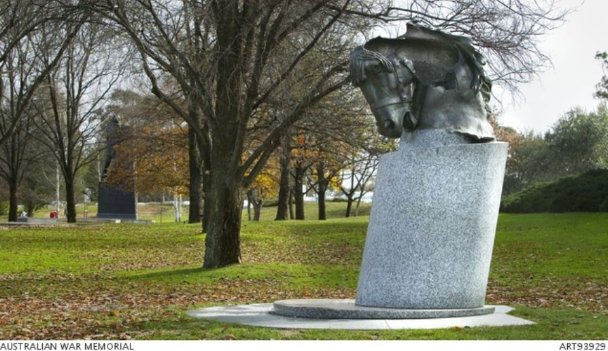

Figure 2.21 Animals in War memorial (Source: Australian War Memorial).

The Animals in War Memorial is a joint project between the Australian War Memorial and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA).

The memorial commemorates those animals that served alongside Australians in all conflicts. It recognises the practical and psychological roles animals have played during times of war and conflict. The Animals in War Memorial incorporates as its centrepiece a large bronze horse head, the only remaining fragment from the original Desert Mounted Corps memorial. The Desert Mounted Corps memorial was designed by Charles Web Gilbert, temporarily worked on by Paul Montford and completed by Sir Bertram Mackennal. It was installed in Port Said, Egypt and unveiled in 1932 by Australia's wartime Prime Minister Billy Hughes. In 1956 the Desert Mounted Corps memorial was destroyed by rioters during the Suez Crisis. The remaining fragments of this memorial were returned to Australia. A new memorial, made by Ray Ewers and modelled on the original Gilbert design, was installed and unveiled by Sir Robert Menzies at Albany, Western Australia in 1964. A version of this was also installed on ANZAC Parade, Canberra and unveiled by Prime Minister John Gorton in 1968.

Artist, Steven Holland, has positioned the bronze horse head upon a tear shaped plinth made of granite. The height of the plinth allows the memorial to be accessible, encouraging visitors to engage with the horse's head in the same way they might have a personal interaction with animals generally. The horse head is a poignant relic, rich in history, drama and emotion. It provides a tangible link to all animals and in this new setting is a sensitive and symbolic memorial for all animals that have served in war.

Future Memorials

The Site Development Plan (SDP) defines Memorial Placement Principles for the addition of new memorials across the site in the future.14

As at November 2021 the Memorial is engaged with stakeholders to develop new memorial sculptures relating to Australia’s wartime nurses, the ‘sufferings of war and service’ and the impact of war on the

families of those who have served and serve today. Each of these sculptures is being developed in accordance with the SDP and in close co-ordination from the affected communities.

2.4.2 The Eastern Precinct

Between 2007 and 2014, the Memorial also undertook major works in the Eastern Precinct, to bring the Eastern Precinct up to the high design standard of the Western Precinct, whilst maintaining the informal woodland character, and visual relationship with Mount Ainslie. The works included the demolition of the Outpost café and construction of a new accessible cafe, Poppy’s; improved outdoor areas and facilities; a new forecourt area containing the National Service Memorial; and improved access and coach and visitor parking. The project won the Canberra Medallion, the highest award at the Australian Institute of Architects (AIA), ACT Chapter Awards, the Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture and the National Award for Urban Design at the National AIA Awards.

Memorials installed in the Eastern Precinct include the ‘Elevation of the Senses’ (2015) memorial.

Figure 2.22 Elevation of the Senses (Source: Australian War Memorial)

This sculpture commemorates the vital role and contribution of Explosive Detection Dogs and their handlers in war.

The tunnel through the base of the sculpture alludes to the rigorous training undertaken by the dogs, while the rocky outcrops atop the columns represent the foreign landscapes to which the dogs and their handlers are deployed. The elevation of the dog on the central column, where it crouches eye-to- eye with its handler, highlights the deep bonds that are forged between the two, as well as the mutual dependence on which their work is based. The configuration of the columns refers to the agility and obstacle courses undertaken by the dogs, as part of their training. Within the main column is a hidden cache of weapons, visible only from the back of the sculpture in order to illustrate the danger of buried

IEDs or hidden weapons that only the dogs can find with their heightened sense of smell. Sitting in the bag, which forms the smallest component of the sculpture, is a tennis ball. The tennis ball is an integral part of the dog’s training, as well as a valuable reward when the animal has located explosives. Ewen Coates (1965- ) is a Melbourne based sculptor and painter.

In 2020 an expansion of the underground parking facility beneath Poppy’s Café was completed as part of the enabling works preceding the Memorial’s Development Project. In addition to delivering an additional 123 permanent parking spaces for visitors the expansion also provides for additional bicycle storage and is plumbed to provide charging stations for electric bicycle and scooters in future.

During the major construction works period of the Development Project a temporary car park has been created on the upper level of the underground car park to the temporary increase in traffic associated with trade works. At the completion of the Project in 2028 this area will be returned to a native bushland state in keeping with the broader landscape heritage values of the Eastern Precinct.

Under the Memorial’s SDP this area is designated as a site for possible future expansion for collection services buildings and the new underground car park structure has been designed to accommodate a two storey building above ground if necessary.

2.5 Australian War Memorial Development Project 2019-2028

On 1 November 2018, the Australian Government approved, and committed funding for the Australian War Memorial (Development Project (the Project). This section includes text provided by the Memorial.

The scope of the Project is to construct additional exhibition spaces to enable the Memorial to continue to comply with the Australian War Memorial Act 1980; to equitably tell the stories of all Australian servicemen and women who have served overseas in conflicts and operations. This section provides additional information, prepared by the Memorial, on the background and development of the Project.

2.5.1 Project Development

In 2014 the Memorial identified, through its business planning process, the need to examine how it would tell the stories of recent and then ongoing service in wars and on peacekeeping and peacemaking operations. This was included as a priority in its 2014-17 Corporate Plan and research undertaken into possible ways to meet this need.

In 2017 the Memorial received funds under a New Policy Proposal to Government for an Initial Business Case (IBC) to examine this need.

The IBC was scoped to examine the following four key issues:

- a lack of capacity to provide equitable coverage of conflicts and operations;

- a lack of capacity to describe a broader description of war;

- a lack of circulation space; and

- poor accessibility and access.

2.5.2 Initial Business Case (2017)

The Initial Business Case (IBC) undertook an initial, broad, approach to examining the four key issues presented above before moving to more detailed examination of options

The broad options were considered in five categories. Each of the solutions considered within each category was not a holistic approach to meet the need for the Project, but a measure that could contribute to a holistic solution. The five categories, including the base case option of “do nothing” were:

(a) Do Nothing

This is the current scenario and does not provide for any changes to be made to the function, buildings or operations of the Memorial at the Campbell site.

(b) Managed Based Approaches

Options to define solutions to the Memorial’s existing challenges through minor operational changes, without significant capital expenditure.

(c) Commercial and Leased Space

Options to consider the extent to which the existing constraints of the Memorial could be mitigated, either nearby to, or remote to, the Memorial, through the leasing of exhibition or storage space.

(d) Adaptive Reuse

Options to consider how the existing facilities at the Memorial might be adaptively re-used to allow for additional exhibition space. Allows for minimal capital works expenditure.

(e) Construction

Options to undertake capital works to reduce or eliminate the existing constraints on the Memorial.

Initial Business Case Options Analysis

Within each IBC category, except for the base case of ‘do nothing’, a more detailed series of options were examined.

(a) Management-based approaches assessed were:

- Restrictions on the number and timing of visitors;

ii. Use of the Memorial’s Mitchell storage facility;

iii. Additional travelling exhibitions/relocatable satellite facility;

iv. Travelling exhibitions to state capital museums, memorials/shrines; and

v. Travelling exhibitions to existing Defence museums.

(b) Commercial and leased space options assessed were:

- Lease Anzac Park East or West;

ii. Offsite leased exhibition space; and

iii. Offsite leased storage, administration and back of house functions.

(c) Adaptive reuse options assessed were:

- Refurbishment of Campbell site;

ii. Refurbishment of the Administration Building and Bean Building; and

iii. Refurbishment of the Mitchell site.

(d) Construction options assessed were:

- Initial redevelopment for the current requirement;

ii. Staged redevelopment onsite for immediate critical constraints;

iii. Develop the precinct for the likely future requirements;

iv. Satellite facility at Anzac Park East and West;

v. Alternative initial redevelopment for the current requirement;

vi. Satellite facilities in surrounding area (Goulburn, NSW; Fairbairn, ACT); and

vii. Satellite facilities in other States/Territories.

Initial Business Case—Conclusion

The conclusion of the IBC assessment was that in order for the Memorial to meet its obligations as defined in the Australian War Memorial Act 1980 and to meet the future needs of the Memorial there was a requirement to undertake construction and refurbishment of existing assets at the Memorial’s Campbell site.

This was primarily based on the requirement for the Memorial to maintain its social significance at the heart of national commemoration, and the belief that all Australian servicemen and women deserve to be commemorated equitably at the Memorial.

2.5.3 Detailed Business Case—Development of Options

As part of the Initial Business Case process the Australian government accepted the Memorial’s recommendation that the option that best met the need for the Project was the construction of additional gallery space on the main Memorial site at Campbell. This led to the development of a Detailed Business Case in 2018.

The Detailed Business Case commenced with the development of a User Requirements Brief which investigated and recorded the specific project requirements through a detailed analysis of each of the Memorial’s three functions. Concurrent with the development of the User Requirements Brief, detailed investigations into the conditions and constraints of both the existing buildings and the site were undertaken.

On completion of the User Requirements Brief and the site investigations, a Functional Design Brief was developed. The Functional Design Brief set down the specific functional and spatial requirements for the Project. This Functional Design Brief included an analysis of the conflicts and operations and the amount of space required to appropriately and equitably tell those stories.

The Functional Design Brief was approved by the Memorial Council which formed the basis of the Project cost and built outcomes proposed to Government as part of the Detailed Business Case submission. The Functional Design Brief also established the requirements to be delivered through the design process.

Design Outcome to be achieved through Detailed Business Case Stage

The design outcomes from the Detailed Business Case process were intended to identify the broad scope and develop, analyse, and assess locations for the additional space to be created for the Project.

Precinct Solution for Additional Gallery Space—Options Development

At the start of the design process, a four-day design charrette was conducted in which five senior architects and ten Memorial staff participated. As part of the design charrette, all possible options to create additional space to meet the User Requirements Brief were considered. The outcome of the four-day charrette was that four design options were selected to be further developed. These were based primarily on four key variables being:

- the location of a second entrance;

- the location of new gallery space;

- whether the Glazed Link was included; and

- the location of the additional car parking.

There were a number of project elements that were consistent with all options such as the Main Building Refurbishment, Bean Building Refurbishment and Extension, and the construction of a Research Centre between the existing Bean Building and Poppy’s Café.

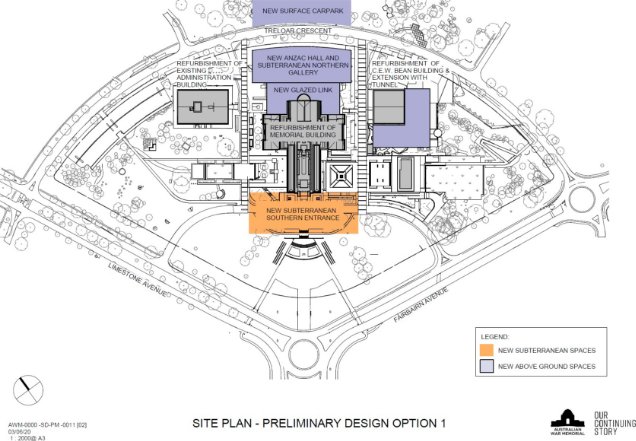

The four options and their key elements in summary are:

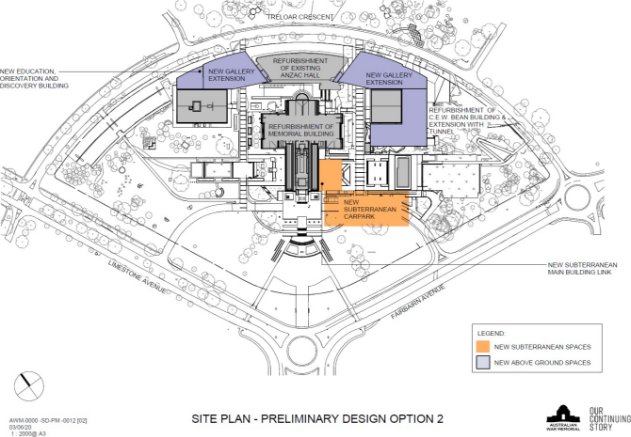

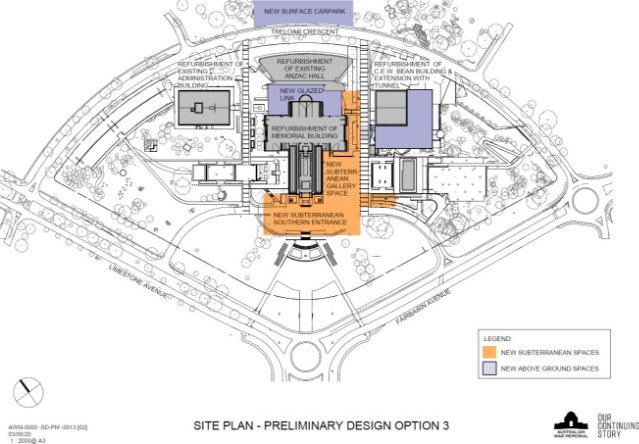

Option 1 Second Entrance South underground New Gallery Space North underground Glazed Link Yes

Additional Car Parking Above ground to the north

Option 2 Second Entrance East underground New Gallery Space North above ground Glazed Link No

Additional Car Parking Underground to the east

Option 3 Second Entrance South underground New Gallery Space East underground Glazed Link Yes

Additional Car Parking Above ground to the north

Option 4 Second Entrance West above ground

New Gallery Space East underground (in existing car park) Glazed Link Yes

Additional Car Parking Multi-level on existing western car park

Project Elements Consistent Across all Options

The Main Building refurbishment, Bean Building refurbishment and extension, and the construction of a Research Centre between the existing Bean Building and Poppy’s Café were consistent in the development of all options, and therefore were not highlighted in the options selection. These elements

and how they interfaced with the options were considered as part of a holistic option that delivered the full Functional Design Brief.

Development Options Considered

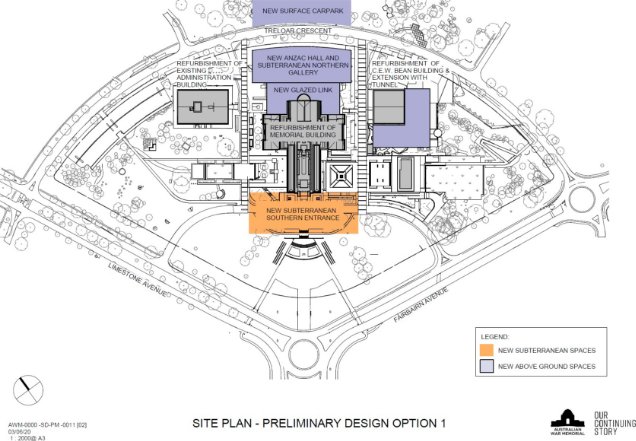

Option 1 – Gallery Space Underground to the Immediate North of the Main Building

Option 1 included the following key locations of additional space:

- Second Entrance South underground

- New Gallery Space North underground

- Glazed Link Yes (between New Gallery Space and rear of Main Building)

- Additional Car Parking Above ground to the north

Option 1 originated as the JPW Masterplan 2017 and was amended to the assessed design solution through the early design process. The basis of this design was a desire to keep development on the site as compact and easy to navigate as possible, with new galleries close to the heart of the Main Building whilst maintaining the north-south axis.

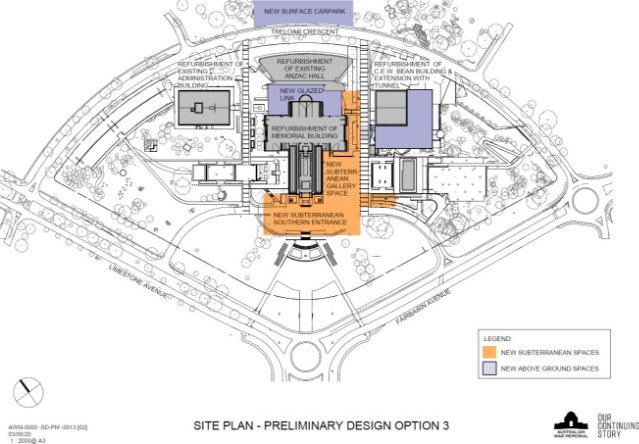

Figure 2.23 Option 1 Additional gallery space to the immediate north of the Main Building, with Glazed Link included (Source: Australian War Memorial).

Option 2 – Gallery Space Underground to the East of the Main Building

Option 2 included the following key locations of additional space:

- Second Entrance South underground

- New Gallery Space East underground

- Additional Car Parking Above ground to the north

The basis of this design option proposes a subterranean development of the site that is primarily below ground to the east of the Main Building. A southern entry is provided in a similar way to what is proposed in Option 1. The basis of the design was to test a fully subterranean option using the rising land to the east, therefore minimising visual impact across the site and maintaining the primacy of the Main Building. This provided galleries in close proximity to the Main Building, but on a parallel north- south axis rather than along the main north-south axis.

Figure 2.24 Option 2 – Additional gallery space to the east and west of Anzac Hall (Source: Australian War Memorial)

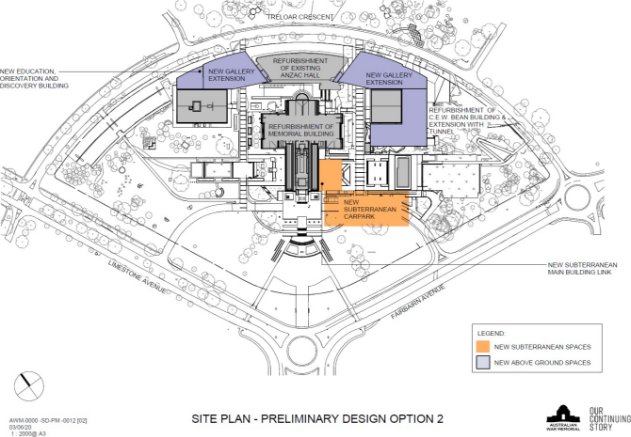

Option 3 – Gallery Space to the North to be connected to the East and West of Anzac Hall

Option 3 included the following key locations of additional space:

- Second Entrance East underground (in existing car park)

- New Gallery Space North above ground

- Additional Car Parking Underground to the east

The basis of this design option proposes that additional gallery space required to achieve the Functional Design Brief is achieved via gallery extensions through eastern and western connections to Anzac Hall. The new northern galleries were repositioned within the Memorial’s precinct to reduce environmental impacts and planning and approval risks

Figure 2.25 Option 3 – Additional gallery space underground to the east of the Main Building (the only above ground change is the glazed link between the Main Building and Anzac Hall) (Source: Australian War Memorial).

Option 4 – Above Ground Western Entrance and Gallery Space to the East of the Main Building

Option 4 included the following key locations of additional space:

- Second Entrance West above ground

- New Gallery Space East underground (in existing car park)

- Additional Car Parking Multi-level on existing western car park

The basis of this design option proposes the use of the underground car park space directly adjacent to the east of the Main Building as gallery space, and an alternative entry to the west of the Main Building that is related to a new above ground car park structure at the western end of the site. This option uses the fall of the land to the west to enable the top of the western extension to be set to the existing ground level of the existing underground car park to the east which results in the two sides of the Memorial being symmetrical as viewed from Anzac Parade

Figure 2.26 Option 4 – New entrance pavilion to the west and gallery space underground to the east

Assessment of the Options