![]()

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan 2021

![]()

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan 2021

© Copyright Director of National Parks, 2021

This management plan has been prepared by the Director of National Parks and the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management and sets out the way the park will be managed for the next 10 years.

Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights can be addressed to:

Director of National Parks GPO Box 787

Canberra ACT 2601

Director of National Parks Australian Business Number (ABN): 13 051 694 963 A copy of this plan is available online at:

environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications

Further information about the park can be found at:

environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/Uluṟu-Kata-Tjuṯa-national-park

How to cite this document

Director of National Parks 2021. Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan 2021. Director of National Parks, Canberra.

Acknowledgments

The Director of National Parks and the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management are grateful to the many individuals and organisations who contributed to the preparation of this management plan. In particular they acknowledge Aṉangu, Parks Australia staff, the Central Land Council, and the Northern Territory and Australian Government agencies that provided information and assistance or submitted comments that contributed to the development of this management plan.

Credits

Maps

Environmental Resources Information Network.

Photography

Parks Australia, Tourism Australia, Tourism NT, Grenville Turner, and Stanley Breeden.

Artwork

Minyma tjuṯa tjitji tjuṯa mai wiṟu mantjini – Women and children collecting good bush foods © Kunmaṉara Taylor, Lillian Inkamala, Pollyanne Mumu, Theresa Taylor, Dulcie Moneymoon, Edith Richards/Copyright Agency.

© Kunmaṉara – ‘Working Together’ Painting.

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management’s vision and goals

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management’s vision and goals

Vision

Ngura nyangangka, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park-ngka, Ananguku Tjukurpa kunpu kanyilkatipai Aṉangu malatja tjutaku.

Goals

• Tjungungku, lipulangku, Aṉangu munu piranpaku Tjukurpa wanungku, wangkara, kulira, wirura palyalkatintjaku.

• Atunymankula kanyintjaku Tjukurpa pulkanya kunpu ngarakatintjaku.

• Ipilypa wanka nyinantjaku wiru tjuta pakaltjinkuntjaku Aṉangu tjutaku, malatja tjutaku.

• Nganana Aṉangu tjuta, visitor tjutaku pukularipai munu palumpa tjanampa wiru tjuta Tjukurpawanungku palyalkatintjaku, Ananguku wiru tjuta kulu ngarakatintjaku.

And through this:

• Ngura winkinguru, World Heritage-ku ngura nyangatja miranwanintjaku.

Vision

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is a place where Aṉangu law and culture is kept strong for future generations.

Goals

• To work and make effective decisions together as equals, using Aṉangu and Piṟanpa knowledge and skills.

• To protect and maintain strong Tjukurpa, culture and country.

• To build livelihoods and other benefits for Aṉangu, particularly young Aṉangu.

• To provide fulfilling experiences based on culture and nature that benefit Aṉangu, who welcome visitors as their guests.

And through this:

• To create one of the world’s great World Heritage Areas.

ii Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan 2021

Foreword

Foreword

© Daisy Walkabout

As we walk towards this vision we will prepare the right pathway for the young to follow. We have always passed on our knowledge to the next generations.

Our vision and goals will guide and provide the direction for implementing this management plan. We will only achieve them by Aṉangu (Aboriginal people) and Piṟanpa (non-Aboriginal people) walking together, side by side, as equals on the same pathway, and by passing on the responsibility for managing the park to future generations.

Aṉangu and Piṟanpa are committed to working and making decisions together to jointly conserve and protect the values of the Park, using a combination of Tjukurpa (Aṉangu law) and Piṟanpa knowledge, skills and obligations. We will also work together to build livelihoods and other benefits for Aṉangu, to help deliver a strong and healthy future for our community, especially for our younger generations.

We warmly welcome visitors from all around the world as our guests and want them to learn about and respect our culture and country. We also want visitors to have fulfilling experiences based on culture and nature, and to return safely to their homes and families, sharing the knowledge and experiences they have gained about this special place.

By achieving our vision and goals, we will create one of the world’s great World Heritage areas, ensuring that the Park’s cultural and natural values are protected and maintained for future generations.

The Board will apply adaptive management principles in four actions:

• Palyal katima – Keep working

• Nyaku katima – Keep checking

• Wangka katima – Keep talking

• Tjukaruruma – Keep straightening

Part A – About Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park iii

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

5.1 Visitor experience and site management 81

5.2 Information, education and interpretation 84

5.3 Promotion, marketing, film and photography 87

6. Administration and business management 94

6.1 Capital works and infrastructure 95

6.2 Resource use 97

6.4 Compliance and enforcement 101

6.5 Subleases, licences and associated occupancy issues 102

6.6 New activities not otherwise specified in this plan 103

Appendix A | English glossary | 106 |

Appendix B | Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara words used in this plan | 110 |

Appendix C | World Heritage values of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park | 112 |

Appendix D | National Heritage values of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park | 114 |

Appendix E | Commonwealth Heritage values of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park | 116 |

Appendix F | Legislative context | 118 |

Appendix G | Summary of the process used to prepare this plan | 129 |

Appendix H | EPBC Act and TPWC Act listed threatened species occurring in Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park |

131 |

Appendix I | EPBC Act listed migratory species occurring in Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park | 132 |

Appendix J | European history of the Park | 133 |

Appendix K | Significance of the Park | 134 |

Appendix L | Provisions of the lease between the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust and the Director of National Parks |

136 |

![]()

![]()

Figures

|

Approximate present-day extent of Western Desert language speakers |

|

Location of protected areas and reserves surrounding the Park | ||

Figure 4: | Visual representation of the layout of this plan | 20 |

Figure 5: | Summary of the structure of this plan | 21 |

The shared decision making and planning process for the Park | ||

Example of how the Board discussed and approved major items in the preparation of this management plan |

| |

Aṉangu perception of the landscape with major landmarks extending outside the Park boundary © Rene Kulitja |

|

Tables

|

|

|

Consultation requirements and decision-making process for action in the Park | ||

Introduced animal species at Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park and their effects on cultural and natural values |

| |

![]()

![]()

![]()

About Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park

Tjukurpa atunymananyi

Protecting and conserving the cultural and natural values of the Park

Establishment of the Park

© Rene Kulitja

We’re happy with visitors coming to our country—they’ve been coming here for a very long time. Our first experience with the tourists was when they were actually coming and staying inside the community.

On 24 May 1977, the Park became the first area to be declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (Cth) which was superseded by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) (Cth). The Park was originally named Uluṟu (Ayers Rock–Mount Olga) National Park, and was declared over an area of 132,550 hectares to a subsoil to a depth of 1,000 metres (this was amended in 1985 to include an additional 16 hectares of land). The Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission (the successor to the Northern Territory Reserves Board) carried out the day-to-day management of the Park.

In February 1979, a claim was lodged under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (the Land Rights Act) by the Central Land Council on behalf of Nguraṟitja, for an area of land that included the Park. At that time, the Aboriginal Land Commissioner did not recommend the land claim be granted as the land had ceased to be unalienated Crown land upon its proclamation as a National Park. However, in 1983 the Prime Minister, Bob Hawke announced that the Park would be returned to its traditional owners on the condition that it was leased to the then Director of National Parks and Wildlife to be managed as a National Park. On 2 September 1985 the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act and the Land Rights Act were amended to put into place joint management of the Park between Nguraṟitja and the Director

of National Parks and Wildlife. These amendments provided for the area of the Park to be granted as inalienable freehold land to the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust. The Land Trust immediately leased the Park to the Director of National Parks and Wildlife, to be managed under a Board of Management with an Aṉangu majority.

At a major ceremony at the Park on 26 October 1985, the Governor-General formally granted title to the Park to the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust. The inaugural Board of Management was gazetted on 10 December 1985 and held its first meeting on 22 April 1986. In the same year, arrangements with the Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission that had been in place since 1977 ceased, and since that time staff of the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (now Parks Australia), have carried out the

day-to-day management of the Park. In 1993, at the request of Aṉangu and the Board of Management, the Park’s official name was changed to its present name, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park.

Aboriginal land and joint management

© Nyininku Lewis

We are on Aboriginal land, it belongs to us and we are looking after it. This means that our system of law must govern the way the land is protected here.

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is a living cultural landscape that is and has always been home for Aṉangu, the traditional owners of the park and its surrounding lands. Aṉangu is the term used by Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people, from the Western Desert region of Australia, to refer to themselves.

Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara are two of the principal dialects spoken in the park, with these language groups extending throughout the central desert region (Figure 1).

Nguraṟitja is the term given to traditional owners that have direct links and rights to the land that encompasses the park. The term ‘traditional Aboriginal owners’ is defined in the Land Rights Act as a local descent group of Aboriginal people who have common spiritual affiliations with the land, or who are entitled by Aboriginal tradition to use and forage over a region. Tjukurpa is referred to consistently throughout this plan and refers to the system of Aṉangu law, history, knowledge, religion and morality that binds people, landscape, plants and animals.

Brisbane

Brisbane

The park is owned by the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust (which is composed of the traditional owners of the park) and covers approximately 1,325 square kilometres of the central desert. The Ayers Rock Resort at Yulara, which adjoins the park’s northern boundary, is owned by the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation. Both the park and the resort are surrounded by the Kaṯiṯi-Petermann Indigenous Protected Area (IPA). Declared in 2015, this IPA incorporates 50,432 square kilometres of Aboriginal freehold land. It is comprised of the Petermann Aboriginal Land Trust (44,993 square kilometres, declared in 1978) and the Kaṯiṯi Aboriginal Land Trust (5,431 square kilometres, declared in 1980).

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park and the Kaṯiṯi-Petermann IPA form part of a series of connected protected areas that cross the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia borders, protecting almost 200,000 square kilometres of central desert (see Figure 2). This network of protected areas contains a vast number of sites of cultural importance to Aṉangu, with Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park being part of an extensive Aboriginal cultural landscape that stretches across the Australian continent.

Part A – About Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park 3

The park represents the interaction of Aṉangu and nature over thousands of years, and its landscape has been managed using Aṉangu knowledge and skills governed by Tjukurpa. Through the declaration of the Kaṯiṯi-Petermann IPA and joint management of the park, Aṉangu are involved in land management activities and the maintenance and conservation of cultural heritage across a vast area of the central Australian desert.

Joint management of the park has been in place since 10 December 1985 when the Board of Management was first established. From this time Nguraṟitja and Piṟanpa have been working and sharing decision-making together to manage the park’s cultural and natural values (see Chapter 2 Working and making decisions together).

Joint management relies on a commitment to look after country and culture by keeping Tjukurpa strong and meeting obligations under Piṟanpa law, particularly the park lease agreement, the Land Rights Act, the EPBC Act and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth) (EPBC Regulations). Joint management also aims to ensure visitors have the best opportunity to enjoy, appreciate and learn about the park and Aṉangu culture.

Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area

Lake MacDonald

Indigenous Protected Area National Park / Reserve Lake

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() N

N

![]()

![]() Sealed road Unsealed road State border

Sealed road Unsealed road State border

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Tjoritja / West MacDonnell National Park

Tjoritja / West MacDonnell National Park

![]() R

R

![]()

![]()

![]() 0 50

0 50

100 km

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() C

C

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Lake Hopkins

Lake Hopkins

![]()

![]()

![]() Lake Neale

Lake Neale

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Finke Gorge National Park

Finke Gorge National Park

![]()

![]() Lake Amadeus

Lake Amadeus

Watarrka National Park

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() CKE

CKE

![]() Ngaanyatjarra Indigenous Protected Area

Ngaanyatjarra Indigenous Protected Area

Katiti Petermann Indigenous Protected Area

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Angas Downs Indigenous Protected Area

Angas Downs Indigenous Protected Area

NORTHERN TERRITORY SOUTH AUSTRALIA

![]() Kalka - Pipalyatjara Indigenous Protected Area

Kalka - Pipalyatjara Indigenous Protected Area

![]() Apara - Makiri - Punti Indigenous Protected Area

Apara - Makiri - Punti Indigenous Protected Area

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Watarru Indigenous Protected Area

Watarru Indigenous Protected Area

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Walalkara Indigenous Protected Area

Walalkara Indigenous Protected Area

Antara - Sandy Bore Indigenous Protected Area

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tjukurpa and a living cultural landscape

© Sammy Wilson

Everything has meaning, everything of the land: trees; grasses; creeks; dunes; and hills. Absolutely everything holds law.

Tjukurpa is the foundation of Aṉangu life and can be defined as Aṉangu law. However, its deeper meanings are far more complex. It includes systems of history, knowledge, philosophy, religion, morality and human behaviour that must be followed to live in harmony with each other and with the land. It also defines the relationships between Aṉangu, the landscape, and those who visit the land. For further more information about Tjukurpa, see Feature Box 1.

According to Tjukurpa, there was a time when ancestral beings, in the forms of humans, animals and plants, travelled widely across the land and performed feats of creation and destruction. The journeys of these beings are remembered and celebrated, and the record of their activities exist today in the features of the land itself. For Aṉangu, this record provides an account and the meaning of the cosmos for the past and the present. When Aṉangu speak of the many natural features within the park, their interpretations and explanations are expressed in terms of the activities of particular Tjukurpa beings, rather than by reference to geological or other explanations. Therefore, the cultural significance of the park to Aṉangu not only includes the park's physical landscape, but also the detailed and extensive body of cultural knowledge associated with this landscape.

Around Uluṟu there are many ancestral sites with strong links to Tjukurpa. Within this cultural landscape there is a system of gender-based cultural knowledge and responsibilities, where Aṉangu men are responsible for looking after sites and knowledge associated with men’s law and culture, and Aṉangu women are responsible for looking after sites and knowledge associated with women’s law and culture.

Tjukurpa contains information not just about the landscape features, but also the ecology, the plants and animals, and appropriate use of areas of the park. Tjukurpa has been passed down through the generations and some information can be shared with visitors. Within the bounds of appropriate access to cultural knowledge, Tjukurpa is the source of much of the information for the interpretation of the park, as Aṉangu want visitors to understand how they see this landscape and to learn about Tjukurpa, Aṉangu culture and the park.

Tjukurpa is the foundation of Aṉangu life and encompasses:

• Aṉangu religion, law and moral systems

• the past, the present and the future

• the creation period when ancestral beings created the world as it is now

• the relationship between people, plants, animals and the physical features of the land

• the knowledge of how these relationships came to be, what they mean, and how they must be maintained in daily life and in ceremony

• strengthening family relationships by visiting relatives in other communities

• raising strong children and ensuring that knowledge is passed onto the next generation

Tjukurpa is the foundation of Aṉangu caring for country and includes:

• finding water and bush foods

• learning about, collecting and using bush medicines, food and seeds

• hunting and gathering certain foods at the right times of the year

• visiting country and keeping it alive, through stories, ceremony and song

• cleaning and protecting waterholes

• traditional burning techniques

• visiting and protecting sacred sites

• keeping visitors, Aṉangu men and women safe

• keeping the Muṯitjulu Community (home to many Aṉangu) private and safe

• keeping women away from men’s sites and keeping men away from women’s sites

• old men passing on knowledge and teaching stories to young boys and men

• old women passing on knowledge and teaching stories to young girls and women

• putting roads, park facilities and infrastructure in proper places so that sacred places are safeguarded

• teaching visitors including park staff and other Piṟanpa how to observe and respect Tjukurpa

Part A – About Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park 7

![]() World Heritage listing

World Heritage listing

© Sammy Wilson

Since the beginning of time, Aṉangu have continued to hold this place of significant law.

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is listed as a world heritage area due to the combination of ongoing Aṉangu cultural traditions, and the park’s outstanding natural features. The park was first inscribed on the World Heritage List for its natural values in 1987 and was subsequently re-inscribed for its cultural values in 1994. The park meets four criteria of outstanding universal value as set out in the World Heritage Convention (see Appendix C), and is one of only 38 sites listed internationally for both cultural and natural heritage.

The immense rock formation of Uluṟu and rock domes of Kata Tjuṯa are remarkable geological and landform features that have special significance to Aṉangu under Tjukurpa, Aṉangu law. Uluṟu is a huge, rounded, red sandstone monolith that is 9.4 kilometres in circumference, and rises over 340 metres above the surrounding sand plain. Rock art in the caves around its base provide evidence of the enduring cultural traditions of Aṉangu. About 32 kilometres to the west of Uluṟu lie the 36 steep-sided domes of Kata Tjuṯa. The domes cover an area of 35 square kilometres and rise to a height of 500 metres above the surrounding plains. This area is sacred under Aṉangu men’s law and, as such, detailed cultural knowledge of it is restricted.

The World Heritage values of the park will be described in a Statement of Outstanding Universal Value, which was being finalised for the park at the time of preparing this management plan. The primary purpose of a Statement of Outstanding Universal Value is to be the key reference for the future effective protection and management of the property. When the park was listed in 1987 and 1994 a Statement of Outstanding Universal Value was not required. Until that statement has been finalised, the World Heritage inscriptions for cultural and natural criteria (see Appendix C) are illustrative of the values of the park and will be used as a guide to the Outstanding Universal Value of the property until the adoption of an official statement.

Chapter 3 Caring for culture and country describes how World Heritage values of the park are managed, with prescriptions and actions that aim to protect these values from actual or potential threats. Essential to this is maintaining Tjukurpa, and incorporating Aṉangu cultural knowledge and skills into the park’s management programs. In addition, a fundamental element of joint management is that Aṉangu cultural knowledge and skills are incorporated into the decision-making processes relating to management of the park (see also Chapter 2 Working and making decisions together).

Australia has national legislation to protect its World Heritage properties through the EPBC Act, and through these obligations, honours a number of international agreements including the World Heritage Convention (see Appendix F).

![]()

Part B – Chapter 1

Part B – Chapter 1

General provisions and IUCN category

Tjukarurungku atunymankunytjaku munu IUCN tjara

Supporting the aspirations of Nguraṟitja

© Nellie Patterson

This plan should be a strong document that future generations can believe in. They will see that, ‘of course, this belongs to us, this sets out all the things we have to do. It has been laid out really carefully for us by our predecessors.’

1.1 Short title

This management plan may be cited as the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan or the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Management Plan.

1.2 Commencement and termination

This management plan will come into operation following approval by the Minister under s.370 of the EPBC Act, on a date specified by the Minister or on the day after it is registered under the Legislation Act 2003 (Cth). This management plan will cease to have effect 10 years after that date, unless it is revoked or replaced with a new plan sooner.

1.3 Planning process

The EPBC Act requires the Park’s Board of Management and the Director of National Parks to prepare a management plan for the park which takes into account the interests of traditional owners and any other Indigenous person interested in the park. Once the draft management plan has been prepared the Director must seek comments on the draft from the public, the Central Land Council and the Northern Territory Government before finalising the management plan and providing it to the Minister.

This is the sixth management plan for the park. The fifth plan commenced on 9 January 2010, and ceased on 8 January 2020.

Before preparation of this management plan began, the Director reviewed how well the previous plan had been implemented to identify improvements for park management though this plan. The review assessed whether the Director had successfully carried out the actions and policies in the previous plan, and whether the Director had successfully met the aims of each Section of that plan.

The findings of the review suggested potential improvements to aspects of park management, recommending to:

• plan, monitor and report more regularly to provide measures of progress;

• ensure Board resolutions are properly formulated, tracked, and reported on;

• improve opportunities which lead to direct employment of Aṉangu;

• review the status and intent of climate change strategies;

• address the impact of feral species on native wildlife;

• address risks of ageing capital infrastructure, and ensure that park assets meet Australian standards.

These recommendations were taken into account in the preparation of this plan.

In September 2017 the Director published a notice inviting the public and stakeholders to have their say towards the preparation of this plan. Eleven written submissions were received, and the views expressed in those submissions were also considered in the preparation of this plan.

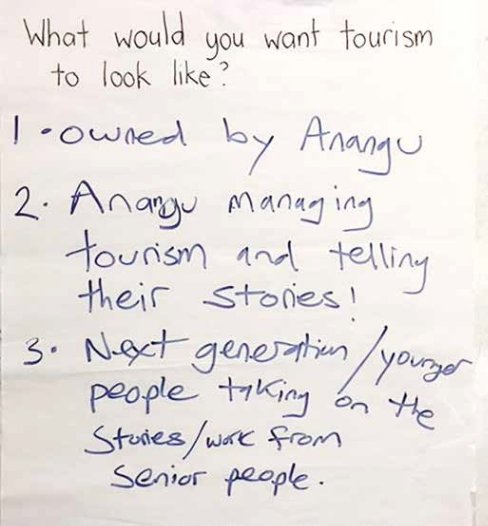

During the drafting stage of this plan, park staff and the CLC also conducted extensive consultations with over 50 Aṉangu during participatory planning meetings, working group meetings and Board of Management meetings. These consultations focused on park management issues related to decision making and working together; cultural and natural resource management; visitor management; Aṉangu employment and the building of other benefits for Aṉangu.

Several other stakeholder groups and individuals were consulted during the preparation of this management plan, including:

• Aṉangu residents of the Muṯitjulu community

• the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Tourism Consultative Committee

• the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Cultural Heritage and Scientific Consultative Committee

• the Central Land Council

• government agencies (The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Executive Director of Township Leasing)

• local Aboriginal associations and corporations, including Aṉangu Jobs and the Muṯitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation (MCAC)

• park staff.

Appendix G provides a summary of the consultations and planning timeframes undertaken in developing this plan.

![]() Kuranyu Kutungku Nyakukatima Think for the future Kuranyu Kutungku Palyalkatima Working for the future Tjitji malatja tjutaku For our young children

Kuranyu Kutungku Nyakukatima Think for the future Kuranyu Kutungku Palyalkatima Working for the future Tjitji malatja tjutaku For our young children

![]() Paluru tjanalpi ma-palyalku Do it for them

Paluru tjanalpi ma-palyalku Do it for them

![]()

![]() Tjitji malatja malatjanku For our descendants

Tjitji malatja malatjanku For our descendants

© Rene Kulitja and Yuka Trigger

The importance of the park’s cultural landscape is recognised through the inscription of its cultural and natural values on the World Heritage List and on the Australian Government’s Commonwealth and National Heritage Lists. The World Heritage values of the park are described in Appendix C; its National Heritage values in Appendix D; and its Commonwealth Heritage values in Appendix E. The park is also significant regionally, nationally and internationally in terms of conservation, social and economic considerations

(see Appendix K).

Table 1 shows the park’s Values Statement, which summarises the attributes that are fundamental to the park’s purpose and significance. Identifying and recognising these values ensures a shared understanding about what is most important about the park, and helps to focus management and planning processes. If the values are allowed to decline, the park’s purpose and significance would be jeopardised. The foundation for managing these values includes the protection provided by the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations. For more detail on protecting and enriching the park’s values, see Chapter 3 Caring for culture and country.

Table 1: Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Values Statement1

Table 1: Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Values Statement1

Background

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is jointly managed park by the park’s traditional Aboriginal owners and the Director of National Parks. Tjukurpa (law) is the foundation of Aṉangu life, and the park is managed using traditional methods governed by Tjukurpa combined with western science and management practices. The park’s first priority is conserving the significant natural and cultural values of the area that comprise Tjukurpa.

© Tony Tjamiwa

It is one Tjukurpa inside the park and outside the park, not different. There are many sacred places in the park that are part of the whole cultural landscape–one line. Everything is one Tjukurpa.

The park’s landscape is dominated by the iconic massifs of Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa. These two geological features are striking examples of geological processes and erosion occurring over time and provide associated refuge and habitat for a broad range of plant and animal species.

The park was proclaimed in 1977 under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (Cth) and continues as a Commonwealth reserve under the EPBC Act. The park protects an area of approximately 1,325 square kilometres within the Great Sandy Desert bioregion.

International listings

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is listed under the World Heritage Convention for both its natural and cultural heritage attributes. The park meets four criteria for listing under the convention:

• An outstanding example representing significant ongoing geological processes, biological evolution and man’s interaction with his natural environment

• Contains unique, rare or superlative natural phenomena, formations or features or areas of exceptional natural beauty, such as superlative examples of important ecosystems to man, natural features, sweeping vistas covered by natural vegetation and exceptional combinations of natural and cultural elements

• A cultural landscape representing the combined work of nature and of man, manifesting the interaction between humankind and its natural environment

• An associative landscape having powerful religious, artistic and cultural associations of the natural elements

![]()

1This table is to be used in conjunction with the impact assessment procedures in Section 3.3 Assessment of proposals when assessing and considering the impacts of proposals.

Values

Values

Cultural values: A living cultural environment

• The park contains significant physical evidence of one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world, including cultural and sacred sites, rock art shelters and areas of archaeological importance

• The park is home to Aṉangu, who continue to practise their cultural obligations consistent with

Tjukurpa (Aṉangu law)

• Tjukurpa is observed today in the park as it was thousands of years ago. It embodies the principles of religion, philosophy and human behaviour that are to be observed in order to live harmoniously with one another and with the natural landscape

• Aṉangu pass on Tjukurpa through the intergenerational transfer of knowledge to their children

• Aṉangu have a deep understanding of, and connection with, the natural features of the landscape and associated plants and animals, many of which have strong cultural significance

• Aṉangu actively manage the landscape through customary land management practices, and maintain their culture in collaboration with park staff through joint management arrangements with the Australian Government. Aṉangu teach park staff about cultural protocols for working on Aboriginal land

• The park contains the monoliths of Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa that are directly and tangibly associated with the events, living traditions, ideas and beliefs of Aṉangu and form an integral part of the belief system of one of the oldest human societies in the world

• The park contains a number of registered and recorded sacred sites associated with multiple

Tjukurpa stories and ancestral beings

Natural values: Unique rock formations and a rich biota

• The park contains unique rock formations and habitats that are striking examples of geological and erosional processes over time, reflecting the age and relatively stable nature of the Australian continent

• The geological features of the park provide sanctuary, shelter and habitat for plant and animal species that are otherwise restricted within the bioregion

• The park contains a rich and diverse suite of plant and animal species suited to the semi-arid environment, including listed and iconic species

• The park contains reptile diversity unparalleled in other semi-arid systems

• Aṉangu’s land management knowledge and practices over thousands of years have been integral to developing and supporting the rich biota seen today

• Land management in the park today recognises and integrates Indigenous ecological knowledge, skills and management practices

• The park incorporates world class scenic vistas that include exceptional combinations of natural and cultural elements

As a result of these values, the park is of great economic, social and research significance to the community and the broader region.

Under s.367(1) of the EPBC Act, a management plan for a Commonwealth reserve must assign the reserve to an IUCN protected area category. The EPBC Regulations describe the management principles for each IUCN category. The category to which the park is assigned is guided by the purposes for which the park was declared a Commonwealth reserve (see Appendix F). These are to ensure:

The purposes for which Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park was declared are consistent with the characteristics for IUCN protected area category II ‘national park’.

In addition to assigning a Commonwealth reserve to an IUCN protected area category, a management plan may also divide a Commonwealth reserve into zones and assign each zone to an IUCN category. The category to which a zone is assigned may differ from the category to which the reserve is assigned (s.367(2)). The provisions of a management plan must not be inconsistent with the management principles for the IUCN category to which the reserve or a zone of the reserve is assigned (s.367(3)).

In 2017, the Director granted a township sublease to the Executive Director of Township Leasing over an area of the park which includes the Muṯitjulu community. This area, called the Muṯitjulu Township Zone, remains part of the Commonwealth reserve and a World Heritage area and is assigned IUCN category VI ‘managed resource use protected area’ by this management plan (Figure 3). Accordingly, development in the Muṯitjulu Township Zone must occur in a sustainable manner, consistent with the relevant aspects of this management plan, the terms and conditions of the Sublease, and other relevant legislation. For more information, see Section 4.2 Muṯitjulu community.

Prescriptions

1.5.1 The park is assigned IUCN protected area management category II ‘national park’.

1.5.2 The park is divided into two zones, the National Park Zone and the Muṯitjulu Township Zone. The location and boundary of each zone is set out in Figure 3.

1.5.3 The National Park Zone is assigned to Australian IUCN protected area management category II ‘national park’, and will be managed in accordance with the principles set down in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations being:

g. the aspirations of traditional owners of land within the reserve or zone, their continuing land management practices, the protection and maintenance of cultural heritage and the benefit the traditional owners derive from enterprises established in the reserve or zone, consistent with these principles, should be recognised and taken into account.

1.5.4 The Muṯitjulu Township Zone is assigned to Australian IUCN protected area management category VI ‘managed resource use protected area’ and will be managed in accordance with the principles set down in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations being:

1.6 Structure of this management plan

© Board of Management

The tree diagram is a good representation of the management plan to protect this country. Aṉangu want one tree, one single base, from which everything else stems. It’s like a mulga tree: they are plentiful and provide multiple necessities for Anangu. They are one of the most important trees, supplying many things

for survival like honey ants, digging sticks, firewood, and much, much more. It is important to think about the branches, but also to remember it is one whole tree.

This management plan provides the strategic direction for managing the park for a period of 10 years. The Board’s vision statement and four goals (see page ii) clearly define what management of the park seeks to achieve. The structure of this management plan is based around these goals, with Chapters 2 to 5 focused around a specific goal, and their associated objectives, performance indicators, prescriptions and actions. Performance indicators will be included in each year’s park operational plan and reviewed annually, with long term indicators reviewed in the fifth year of the management plan coming into force.

Figure 4 is a visual representation of the structure of this plan, and illustrates how the vision statement and goals link to major chapters. Tree roots are the foundation which is grounded in Tjukurpa and Australian law and the tree trunk represents Aṉangu and Piṟanpa working together. The four branches are the major

chapters of the plan, with each chapter relating to a different one of the Board’s four main goals for this plan. Figure 5 provides a visual summary of the structure of this plan.

Figure 4: Visual representation of the layout of this plan

Figure 4: Visual representation of the layout of this plan

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Management Plan

Management Plan

Aṉangu and Piṟanpa working together

Tjukurpa Australian law

![]()

Part B – Chapter 2

Part B – Chapter 2

Working and making decisions together

Tjungungku kuliṟa tjunkula palyaṉi

Working together, malparara way

Working together, malparara way

2. Working and making decisions together

Joint management is an ongoing and adaptive process which requires Aṉangu and Piṟanpa to actively work together and share decision-making to manage the park. To be successful at jointly managing the park

and protecting its cultural and natural values, we need to include both Aṉangu and Piṟanpa knowledge and priorities when making decisions, and when planning and implementing park operations.

Working and making decisions together occurs at two levels. Firstly, through the Board of Management, where ‘big picture’ or strategic decisions are made in accordance with this plan and the advice of the Board’s working groups. Secondly, guided by the directions of the Board, decisions are made by park staff and Aṉangu when planning and conducting work programs together, to implement this management plan and Board decisions.

This chapter sets out the objectives, prescriptions and actions relating to how Parks Australia and Aṉangu will work and make decisions together to jointly manage Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park.

Snapshot of Chapter 2

Snapshot of Chapter 2

Objectives

Objectives

2.1 Board of Management

The Board and Director make informed and effective decisions together as equals that respect and comply with Tjukurpa, Australian laws and this management plan

2.2 Work planning and implementation

Aṉangu and Piṟanpa plan and conduct work programs together to implement this management plan and the decisions of the Board and Director

To work and make effective decisions together as equals, using Aṉangu and Piṟanpa knowledge and skills.

Performance indicators—What we will check

• How satisfied the Board is with working and making effective decisions together

• Extent by which work programs are planned and carried out by Aṉangu and Parks Australia staff

• Extent by which work programs address actions in this management plan and Board decisions

• Extent by which traditional owner consultation is carried out according to Central Land Council and Board requirements

Objective—What needs to happen

The Board and Director make informed and effective decisions together as equals that respect and comply with Tjukurpa, Australian laws and this management plan

Background

© Nellie Patterson

We want the young to learn about the Board so that if they are elected in the future they will have all the knowledge they need about the park. We won’t be around. The young need to learn from us.

© Stephen Clyne

This plan is an important document for working together. Through this plan Anangu and non-Anangu will be able to properly share their knowledge.

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is one of Australia’s first jointly managed National Parks. Joint management began in 1985 when Anangu ownership of the land was formally recognised by title of the land being granted to its traditional owners under the Land Rights Act. The park was then leased to the Director of National Parks for 99 years (see Aboriginal land and joint management in Part A).

Joint management describes the working relationship between Aṉangu and the Director of National Parks, which is based on working and making decisions together as equals and sharing their knowledge and skills. For joint management to be successful, there must also be mutual trust and respect. At the core of this working relationship is the recognition that there are two law systems that govern the park and the greater region. Therefore, a joint commitment to maintain country and culture can only occur if we respect and comply with Aṉangu law (Tjukurpa) and Piṟanpa (Australian) law—particularly the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations, the Land Rights Act, this management plan and the park lease agreement.

A key aspect of joint management is consulting with Nguraṟitja when making decisions about managing the park. The Director of National Parks and the Central Land Council (CLC) developed traditional owner consultation guidelines which the Board has approved, to assist Parks Australia staff meet the Director’s legal obligations associated with the joint management of the park.

Table 2 shows the decision making process required by this management plan for activities carried out in the park. Consultation requirements and decision making processes are separated into two main categories—routine actions and non-routine actions—depending on the potential impact on the park’s cultural and natural values, visitor use, facilities and infrastructure, and Aṉangu interests. While a key

aspect of joint management, consultation does not replace the need for Aṉangu and the Director continuing to work together as equals to manage the park.

Joint management is an ongoing learning process, and the relationship will adapt and transform because Aṉangu aspirations and other factors change over time. Working together requires active participation from both Aṉangu and Parks Australia staff, as well as from the Board of Management, the Board’s working groups, the Joint Management Partnership Team and the CLC. There are also other people and organisations that may need to be consulted and/or engaged for their expertise when the Board and the Director makes decisions, such as Aboriginal associations, the tourism industry, and experts in cultural and natural resource management.

The roles of each of the people and organisations involved in the joint management of the park is provided in more detail below. Figure 6 is a visual pathway for the shared decision making and planning process for Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park.

Working groups

Joint Management Partnership Team#

Monitoring and review

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan

Park work plan

Aṉangu and Nguraritja

• Working together

• Consultations

• Meetings

Actions

© Kunmaṉara – ‘Working Together’ Painting

*Board of Management is comprised of Aṉangu nominees, the Director of National Parks, a Minister for Tourism nominee, a Minister for the Environment nominee and a Northern Territory Government nominee.

#Joint management partnership team consists of representatives from the Central Land Council, a Mutitjulu Liaison Officer, and the Board Secretariat).

The Board of Management was established in 1985. Under Piṟanpa law (the EPBC Act), the Board must comprise of a majority of Indigenous people nominated by Nguraṟitja. At the time of this plan’s preparation the Board comprises eight Aṉangu members including the Chairperson (who by convention is Aṉangu); the Director of National Parks; a Minister for Tourism nominee; a Minister for the Environment nominee, and a Northern Territory Government nominee.

The Board operates under a set of rules approved by the Board, and its functions under the EPBC Act are outlined in section 2.1.1 of this plan. Two of these functions are, in conjunction with the Director, to prepare management plans for the park; and, to make decisions relating to the management of the park that are consistent with this management plan.

Figure 7 provides an example of how the Board and the Director worked together in a participatory manner to prepare this management plan.

The term Nguraṟitja is used by Aṉangu as a collective term for traditional owners of the park. In the context of this management plan, Aṉangu is a broader word that refers to people with traditional affiliations to the region who may, or, may not be traditional owners/Nguraṟitja. Depending on the type of decisions that need to be made, Parks Australia and the CLC will consult with Nguraṟitja, using the processes in this

management plan and the consultation guidelines approved by the Board. Usually, the Board will ask for the views of Nguraṟitja on a particular issue before making a decision.

As well as being a Board member, the Director has a responsibility under the EPBC Act to administer, control, protect, conserve and manage biodiversity and heritage in Commonwealth reserves. At the time of this plans preparation, many of the Director’s powers under the EPBC Act are delegated to the staff of Parks Australia. The Director is also an ‘accountable authority’ for the purposes of the Public Governance,

Performance and Accountability Act 2013, which governs how the Director uses and manages public resources. The Director also has obligations to protect the interests and culture of Nguraṟitja under the Lease agreement. Funds for managing the park are allocated from the Australian National Parks Fund as provided for by the EPBC Act, and the Director may collect park use fees subject to the approval of the Minister.

Parks Australia is a division of the Department of the Agriculture, Water and the Environment that supports the Director of National Parks to carry out their responsibilities. Parks Australia staff and Aṉangu manage the day–to–day operations of the park by planning and implementing work programs together. Work programs are guided by the prescriptions and actions of this management plan, and by the decisions and directions of the Board and Director. Parks Australia is also required to ensure that relevant government policies and legal requirements are addressed when managing the park.

• The Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust holds title to the park which is owned by Nguraritja. The Central Land Council (CLC) was established under the Land Rights Act and has broad functions to assist and represent the interests of traditional Aboriginal owners of land and other Aboriginal people within Central Australia. CLC, represents Nguraritja for the park and acts on behalf of the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust. The CLC also acts on behalf of the Nguraritja for the Kaṯiṯi and the Petermann Aboriginal Land Trust, which hold title to the land surrounding the park.

• The CLC plays an important role in the joint management of the park by consulting with Aṉangu, monitoring the implementation of the management plan and ensuring that the provisions of the Lease are upheld.

• Under the EPBC Act and the Lease, the Director is required to consult the CLC about park management, specifically in relation to the preparation of management plans. At the time of this plan’s preparation, the Director supports a Joint Management Officer for the park to assist the CLC to carry out these activities and address responsibilities under the Lease. For a more detailed description of the role of the CLC, see Appendix F.

In accordance with the Lease conditions, the role of the Community Liaison Officer (referred to in this plan as the Muṯitjulu Liaison Officer) is to liaise between the Muṯitjulu community and Parks Australia about management activities, and to present Muṯitjulu community views to the Board. The Muṯitjulu Liaison Officer (MLO) position is funded by the Director, and at the time of preparing this management plan is administered by the Muṯitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation (MCAC). For more information about the MLO, see Section 4.2 Muṯitjulu community.

The Joint Management Partnership Team supports the joint management of the park and addresses relevant Muṯitjulu community issues. At the time of preparing this plan, it comprises the CLC Joint Management Officer, Muṯitjulu Liaison Officer, Board Secretary, and the Park Manager. It operates under Terms of Reference determined by the Board.

The Board establishes working groups to assist the Board to carry out its functions, primarily to advise and conduct work delegated by the Board. These working groups are the cultural and natural heritage, tourism, media and Aṉangu employment working groups. Each working group is made up of Nguraṟitja, Parks Australia staff, CLC staff and experts in a particular field. Currently the Board has working groups in the areas of cultural and natural heritage, tourism, media and Aṉangu employment. Each working group operates under terms of reference determined by the Board.

Challenges

• Ensuring Aṉangu and Piṟanpa Board members can make informed and effective decisions together as equals

• Complying with Tjukurpa and Piṟanpa laws and governance requirements when making decisions

• Ensuring working groups function effectively to assist the Board to carry out its functions

• Engaging younger Aṉangu in decision-making related to the park's management, to ensure joint management remains relevant and effective for future generations

• Ensuring Aṉangu priorities and views are considered when making decisions

• Ensuring the implementation of this plan is effectively monitored, reported and evaluated

2.1.1 The Director will provide sufficient and reasonable resources to support the Board to effectively carry out its functions under the EPBC Act, which are:

2.1.2 Joint management decision making and working together by the Director and the Board will be guided by the following principles:

2.1.3 Decision-making by the Director and the Board under this management plan will be consistent with:

2.1.4 The Board will maintain the working groups under this management plan, and may establish new working groups to provide advice and other support to help the Board to carry out its functions (see sections 3.1.9, 4.1.3, 5.1.10 and 5.3.8). The Board will set out terms of reference for working groups established under this section.

2.1.5 Unless otherwise determined by the Board, maintain the operation of the Joint Management Partnership Team.

2.1.6 Develop guidelines and procedures to assist Parks Australia staff to comply with the Director’s obligations under this management plan, including Aṉangu consultation requirements outlined in Table 2.

2.1.7 Support Board meetings in ways that enable all members to effectively contribute to making joint and informed decisions. This may include, but is not limited to:

2.1.8 Report to the Board on the implementation of this management plan and other park management issues, as requested by the Board. This includes reporting on the status of Board decisions and follow up actions.

2.1.9 With the approval of the Board, communicate and disseminate information about Board activities for Aṉangu and Parks Australia staff, such as through joint management newsletters.

2.1.10 Provide opportunities for young Aṉangu to engage in Board and working group forums.

2.1.11 Review the Lease agreement with CLC in consultation with Nguraṟitja every five years.

2.1.12 Schedule the prioritisation and implementation of actions and (relevant) prescriptions in this management plan in conjunction with the Board.

2.1.13 In the fifth year of this management plan coming into force, prepare and present to the Board an audit of the implementation of this management plan. The audit will include, but may not be limited to, the following terms of reference:

Category

Example

Decision making process and

consultation requirements

consultation requirements

Routine actions

Actions that are likely to have no impact, or no more than a negligible impact, on:

• the cultural and natural values of the park;

• the interests of Nguraṟitja, community members and other stakeholders;

• visitor use of the park and facilities and services in the park;

• changes to existing facilities and services in the park

• Minor works to maintain, repair, replace or improve existing infrastructure in its present form and footprint

• Existing routine operations to implement prescriptions or

actions in this management plan or work programs established under this management plan

• Seasonal opening or closing of visitor areas

• Issuing permits for regular activities in accordance with this management plan e.g. existing types of commercial activities carried out in areas of the park generally open to the public (section 5.4.2) and non- commercial research (section 3.1.4)

• Assessment process accords with management plan prescriptions and actions

• Nguraṟitja, community members and other stakeholders are consulted

• Decision is made by the Director or appropriate delegate

Category

Example

Decision making process and

consultation requirements

Non-routine actions

Actions that are likely to have more than a negligible impact, on:

Actions that are likely to have more than a negligible impact, on:

• the cultural and natural values of the park;

• the interests of Nguraṟitja, community members and other stakeholders;

• visitor use of the park and facilities and services in the park;

• changes to existing facilities and services in the park

• Development of new work programs under this management plan

• Minor new works and infrastructure to implement prescriptions in this management plan

• Moderate or major capital works or developments e.g. new infrastructure, or expansion or upgrade of existing infrastructure beyond its current footprint, including realignment of roads

• Major or long-term changes to existing visitor access arrangements

• Changes to the tour guide accreditation course

• Approval of moderate or major works for an existing approved commercial operation, e.g. new infrastructure, expansion or upgrade of existing infrastructure

• Approval of moderate or major capital works in connection with a commercial operation

• Approval of new types of commercial activities

• Issuing of subleases, commercial activity licences or occupation licences

• Assessment process accords with management plan prescriptions and actions

• Nguraṟitja, community members and other stakeholders are consulted in coordination with the CLC where appropriate

• Any relevant working groups engaged

• Relevant stakeholders are consulted and kept

informed about progress of assessments

• Proposal must be approved by the Board before the Director carries out the management activity or issues an authorisation.

Note 1: Some actions may also require a Sacred Site Clearance Certificate from the CLC, see Table 4 in Section

3.3 Assessment of proposals.

Note 2: Actions involving the grant or assignment of a

sublease or other dependent interest by the Director requires the consent of the CLC and

the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Aboriginal Land Trust in accordance with the park lease agreement.

2.2 Work planning and implementation

Objective—What needs to happen

Aṉangu and Piṟanpa plan and conduct work programs together to implement this management plan and the Board’s and Director’s decisions

Background

© Board of Management

Come together to talk and reflect on decisions: one path, one voice.

In addition to making decisions together at the Board level, joint management requires Aṉangu and Piṟanpa to actively work and make decisions together to plan and implement park work programs and operations.

This management plan and the Board and Director’s decisions provides the ‘big picture’ directions to help do this, including for planning, implementing and monitoring operations to manage the park. Park operations are also guided by and must follow Tjukurpa and Australian laws, including the Director’s responsibilities under the EPBC Act and EPBC regulations the Land Rights Act, the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 and the park lease agreement.

A critical aspect of joint management is engaging Aṉangu in park management work programs and operations. This occurs in a number of ways, including through employment in park operations, involvement in Board and working group meetings, and representation on staff selection panels (see Section 4.1 Employment, education, training and other benefits).

As noted in Section 2.1 Board of Management, park staff also consult with Aṉangu on a range of operational issues relating to managing the park by following the procedures in Table 2, and the operational guidelines approved by the Board and Central Land Council. Where relevant, Aṉangu priorities and information arising from these consultations guide the preparation and implementation of work programs.

In addition to the day-to-day park operations, carrying out on-country activities together is another important way of including Anangu knowledge in the park's cultural and natural resource management programs. On- country activities can be defined as excursions or fieldtrips on Aboriginal land carried out over one or more days where Aṉangu and Piṟanpa work together. These activities can be classified into three main groups: intergenerational learning, caring for country and cultural knowledge exchange between Aṉangu and Piṟanpa. On-country activities aim to promote the use of Anangu land management practices, support the intergenerational transfer of cultural knowledge from senior Aṉangu to younger Aṉangu and promote cultural awareness. They also facilitate opportunities for Piṟanpa staff to learn from Nguraṟitja, and for Aṉangu to learn science-based land management approaches, fostering positive joint management relationships.

Some of these activities are conducted in-conjunction with Central Land Council, as several sites of cultural significance are located adjacent to the park in the Kaṯiṯi and Petermann Aboriginal Land Trust (see also Action 3.2.14). Two-way cross-cultural understanding is important for both Piṟanpa and Aṉangu, as it helps to build a shared understanding of cultural perspectives, and nurtures the exchange of skills and knowledge. This is critical for developing strong relationships, mutual respect and enhancing Aṉangu involvement in the management of the park. On-country work is a core aspect of cultural and natural management programs and is discussed in further detail in Section 3.2 Protecting and enriching culture and country.

This section is to be read in conjunction with the prescriptions and actions of Section 2.1 Board of Management.

Challenges

• Ensuring work plans and associated operations address the prescriptions and actions in this management, plan and the Board’s and Director’s other strategic directions and priorities

• Undertaking operations in ways that are jointly planned, culturally appropriate and facilitate the exchange of knowledge between Piṟanpa and Aṉangu park staff

• Supporting the maintenance of Anangu knowledge and skills and fostering positive joint management relationships with park staff as part of park operations

2.2.1 Prepare, implement and monitor work plans to address the prescriptions and actions in this management plan and the Board’s and Director’s other strategic directions and priorities.

2.2.2 Engage and employ Aṉangu when planning and implementing work plans and programs and ensure they are properly supported and mentored.

2.2.3 Develop the skills and capability of staff to undertake park management activities to implement this management plan.

2.2.4 Seek Nguraṟitja involvement on employment panels for ongoing staff appointments, including providing training associated with recruitment processes.

2.2.5 Conduct and document consultations with Aṉangu in accordance with this management plan (see section 2.1.7 and Table 2). Where relevant, incorporate priorities from consultations into work plans.

2.2.6 Conduct joint management inductions and foster the exchange of cross-cultural knowledge and awareness, for both Aṉangu and non-Aṉangu staff.

2.2.7 Conduct cultural activities and on-country trips with Aṉangu and non-Aṉangu staff (see also sections 3.1.11 and 3.2.12).

2.2.8 Formalise joint planning arrangements and representation with Kaṯiṯi Petermann IPA and Yulara.

![]()

Part B – Chapter 3

Part B – Chapter 3

Caring for culture and country

Tjukurpa aṯunymananyi

Tjukurpa aṯunymananyi

Protecting and conserving the cultural and natural values of the park

3. Caring for culture and country

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park has a number of outstanding cultural and natural values, which have resulted in the park being inscribed on Commonwealth, National and World Heritage listings. These values are described in this chapter and also summarised in the values statement in Table 1. For Aṉangu, ‘caring for culture and country’ are inextricably linked. The ongoing land management practices and traditions carried out by generations of Aṉangu in accordance with Tjukurpa, have helped to shape the country we see today and are fundamental to the listing of the park under the World Heritage Convention.

Cultural knowledge and skills are therefore essential in maintaining and enhancing the integrity of the park’s values. Since European settlement, the park’s landscape has altered, with the introduction of invasive plants and animals, altered fire regimes, tourism and associated infrastructure. For these reasons, the application of Aṉangu and contemporary scientific land management practices are essential for managing the park into the future.

This chapter sets out the objectives, prescriptions and actions for managing the cultural and natural values of the park. It also outlines how these values will be protected from current and potential threats, including assessing new activity proposals.

Performance indicators

Performance indicators

• Extent of Aṉangu participation in cultural and natural heritage management programs

• The number of on-country activities conducted

• The number of opportunities to support and document the intergenerational transfer of cultural skills, practices and knowledge

• Whether monitoring programs for significant flora and fauna are carried out

• Whether water extraction from aquifers remains sustainable and water quality is maintained

• The number of rock art and cultural sites monitored and managed

• Whether waterhole management and protection occurs

• The number and extent of active heavily eroded sites

• Whether the distribution and/or abundance of targeted invasive species is decreased

• Whether the frequency, extent and intensity of large-scale fires are reduced

• Whether proposals for new activities are assessed for their impacts in accordance with the management plan

Objectives

Use Aṉangu and contemporary land management skills and knowledge for the protection, maintenance and enrichment of the park's cultural and natural values

and country Protect, maintain and enrich the park's cultural and natural

values and sites

The impacts of proposed actions on park values and Nguraṟitja interests are assessed and considered before decisions are made to approve them

To protect and maintain strong Tjukurpa, culture and country

Performance indicators—What we will check

• Extent of Aṉangu participation in cultural and natural heritage management programs

• The number of on-country activities conducted

• The number of opportunities to support and document the intergenerational transfer of cultural skills, practices and knowledge

• Whether monitoring programs for significant flora and fauna are carried out

• Whether water extraction from aquifers remains sustainable and water quality is maintained

• The number of rock art and cultural sites monitored and managed

• Whether waterhole management and protection occurs

• The number and extent of active heavily eroded sites

• Whether the distribution and/or abundance of targeted invasive species is decreased

• Whether the frequency, extent and intensity of large-scale fires are reduced

• Whether proposals for new activities are assessed for their impacts in accordance with the management plan

3.1 Knowledge for managing country

Objective—What needs to happen

Use Aṉangu and contemporary land management skills and knowledge for the protection, maintenance and enrichment of the park's cultural and natural values

Background

© Nellie Patterson

We have a lot of young people and their education in protecting law and culture needs to start from childhood. They should learn the laws from childhood and then be employed to keep them strong.They should also be learning from ranger staff so the country is held and protected through both cultural systems.

Under Tjukurpa, Aṉangu have always been connected with Uluṟu. According to Aṉangu, ancestral beings created the plants, animals and features of the landscape, and Aṉangu are the descendants of these ancestors that are responsible for protecting and managing country. Knowledge associated with fulfilling these responsibilities has been passed down from generation to generation through Tjukurpa. Strong spiritual associations and interactions between Aṉangu and country continue today, and it is this ongoing relationship with the land that led to the park being included on the World Heritage List for its cultural values. Therefore, looking after country in accordance with Tjukurpa is a primary responsibility shared by the Director and Aṉangu in jointly managing the park.

The physical aspects of Aṉangu cultural heritage, such as sacred sites, rock art and archaeological material, are all also part of the park’s living cultural landscape. The park contains significant physical evidence of one of the oldest continuous living cultures in the world. Sites of significance include rock art sites, stone arrangements, rock engravings and rock shelters containing archaeological deposits. Some of the work undertaken to care for significant sites include protecting rock art by installing visitor viewing platforms, controlling erosion, removing weeds and realigning walking tracks away from sensitive areas. A register of sites of special significance has been established in consultation with Aṉangu, the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority and the Central Land Council. Figure 8 shows some of the significant sites and Aṉangu place names at Uluṟu.

A major part of Aṉangu cultural heritage are the intangible aspects of Tjukurpa. These include the spiritual knowledge about country, sacred sites, ancestral stories and beliefs, language, songs, dances; land use; and cultural practices, ceremonies or rituals. It also includes hunting and gathering techniques which are important cultural activities for reinforcing connection to country, maintaining links with Tjukurpa and passing on knowledge to younger generations.

Aṉangu maintain a detailed body of cultural and ecological knowledge of the land based on thousands of years of continuous habitation in the region. Aṉangu landscape management methods follow a traditional regime of fire management, sustainable hunting and harvesting practices and protection and maintenance of water sources. This knowledge also includes climate patterns, animal behaviour and ecological responses, and the relationships between different elements of the landscape. Aṉangu knowledge and cultural material can be described as Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (See Feature Box 2) which is an essential element of maintaining Tjukurpa. Preserving and maintaining this knowledge through recording Aṉangu oral history and the intergenerational knowledge transfer, helps keep Aṉangu culture strong and maintains knowledge for managing country, for now and the future.

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) is a term used to describe Indigenous cultural material and knowledge. The Board and Parks Australia work with CLC and other stakeholders to ensure ICIP rights

are protected

To Aṉangu it is extremely important to protect their ICIP, which includes but may not be limited to:

• immovable cultural property, including sacred sites and rock art

• cultural objects, including sacred objects and other objects of cultural significance

• contemporary art, including paintings and other works

• human remains, including the remains of Aṉangu ancestors

• traditional knowledge, including spiritual, scientific, ecological and local historical

• stories, including Tjukurpa stories and Aṉangu history and society

• language, including the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara languages

• inma (singing and dancing performances and ceremonies), including recordings

• knowledge of cultural environment resources – including plants, animals and minerals

• images, including photographs, films and artworks of the landscape or people.

Tjukurpa provides rules that protect this material and knowledge from inappropriate access and use by Aṉangu and other Aboriginal people. Today however, ICIP can be accessed and used by non-Aṉangu for a range of purposes.

Aṉangu have concerns about being able to manage and control ICIP, specifically by protecting cultural material; recognising that Aṉangu are the owners of this property; having the capacity to monitor and regulate its use; and being able to benefit from sharing it.

It is the view of Nguraṟitja that, through Tjukurpa, there should be strong links between the management of the park and adjoining lands. This is because areas in the park are closely related to cultural and natural features beyond its boundary. For example, many converging ancestral tracks and Tjukurpa stories that extend across the surrounding lands converge at Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa. Connection to these extended sites has direct implications for the practice and maintenance of Tjukurpa within the park.

Figure 9 highlights some of the important Aṉangu sites that occur both inside and outside the park. These sites include homelands, or outstations, which are small communities built on land of particular cultural significance. There are several homelands located on the Kaṯiṯi-Petermann IPA (see Figure 9 and Figure 10) and these areas are culturally significant for Nguraṟitja. For this reason, working together with traditional owners of the surrounding lands is important for Nguraṟitja in order to help maintain the living cultural landscape and Tjukurpa both inside the park and in the surrounding region.

Station

Station

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Protected areas

Lake

![]()

![]() Sealed road

Sealed road

![]()

![]()

![]() Unsealed road R

Unsealed road R

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 4WD road State border

4WD road State border

N

0 50

100 km

Ntaria (Herbannsburg)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() C

C

Alice Springs

Kaltukatjara (Docker River)

Lake Neale

Lake Amadeus

Ulpanyali

Wanmarra

Utju (Areyonga)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Ukaka

Ukaka

Middleton Ponds

Henbury

![]() Tjunti (Lasseters Cave)

Tjunti (Lasseters Cave)

CKE

![]()

![]() Puta Puta

Puta Puta

Alyapa

![]() Pirrulpakalarintja

Pirrulpakalarintja

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Mutitjulu

Mutitjulu

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Curtin Springs

Curtin Springs

Angas Downs

![]() Imanpa

Imanpa

![]()

![]()

![]() Mount Ebenezer Eridunda

Mount Ebenezer Eridunda

Umutju Mantarur

Walytjatjata

Alpara

Mulga Park

![]() Mount Cavenagh

Mount Cavenagh

NORTHERN TERRITORY

Kalka Pipalyatjara

Kanypi

Angatja

Nyapari

Amata

Walyinynga (Cave Hill)

SOUTH AUSTRALIA

Ngarutjara

Victory Downs

Kunamata

Ulkiya

Umuwa

Pukatja

(Ernabella)

Yunyarinyi (Kenmore Park)

De Rose Hill

![]()

![]() Kaltjiti (Fregon)

Kaltjiti (Fregon)

Wartura (Mt Lindsay)

Walalkara

Kanu Ultu

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Rob Well

Rob Well

Mimili

![]() Iwantja (Indulkana)

Iwantja (Indulkana)

Granite Downs

![]()

![]()

![]()

Parks Australia supports Aṉangu to maintain their cultural heritage and knowledge by facilitating and supporting ‘on-country’ cultural activities, protecting sacred sites and ensuring that sensitive sites are accessible to Aṉangu, whilst being protected from unauthorised or inappropriate visitor use or access (see Section 3.2 Protecting and enriching culture and country). A Cultural and Natural Heritage working group advises the Board on a range of cultural and natural heritage matters. It comprises Aṉangu, scientists, the Central Land Council, cultural heritage specialists and park staff.

In the past, research on Aṉangu society has included the collection of objects and recording of cultural practices, ceremonies and knowledge. In some cases, cultural property was removed from Aṉangu control and deposited in museums, libraries or educational institutions, either in Australia or overseas. Increasingly, the existence of this cultural material is coming to light and its repatriation is important to Aṉangu. For

this reason, a secure ‘keeping place’ was constructed for the community to house sacred and repatriated material. In addition to the keeping place, databases are used to appropriately store and access cultural materials (digital images and sound recordings). Parks Australia also contributes to a cultural heritage database used in the region, called Aṟa Irititja.

The Director has responsibilities to assist Aṉangu protect culturally significant material and important cultural areas within the park. The Land Rights Act, the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations and the park lease agreement all provide legal protection of sacred sites and other sites of significance to Aṉangu, with any ground disturbing works and works in which living or dead trees will be damaged or modified will require a CLC sacred site clearance certificate. The Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT) and the Heritage Act 2011 (NT) are also relevant to the protection of sacred sites and certain objects.