National Film and Sound Archive Heritage

Management Plan 2021

I, Nancy Bennison, Acting Chief Executive Officer of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, make the following plan under s 341S of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

The name of this plan is the National Film and Sound Archive Heritage Management Plan 2021.

Dated 14 September 2021

Nancy Bennison

Acting Chief Executive Officer of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia

Images in this plan have been sourced from the collections of the National Archive of Australia, National Library of Australia and the National Museum of Australia. Additional images of the building have been provided by Eric Martin and Associates.

National Film & Sound Archive

Heritage Management Plan 2021 to 2026

Prepared by

Eric Martin and Associates

For

National Film & Sound Archive

10/68 Jardine St KINGSTON ACT 2604

Ph: 02 6260 6395

Fax: 02 62606413

Email: emaa@emaa.com.au

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) requires that a Heritage Management Plan (HMP) should be prepared for all assets on the National and Commonwealth Heritage Register and that they be updated within every 5 years.

The National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) commissioned this update to check that no new material is to hand, to review and change details as may be required and reconfirm policies. As a separate exercise the NFSA also commissioned an update of the Heritage Strategy.

Since the previous HMP the Theatrette has been refurbished, the South Gallery has re-opened for public exhibitions, the Library and Front Room have been re-purposed for public programs or exhibitions, the Director’s Residence has been leased utilised for researchers and conservation of stonework and courtyard render completed and roof repairs undertaken.

Main Building

The main building is symmetrically placed on a block and is set within a landscape which incorporates the former Director’s Residence as a separate building and car parking and roads. It is in an area surrounded by national institutions such as ANU and Australian Academy of Science (Shine Dome).

The main building is a two-storey masonry building with a full basement. It is clad in Hawkesbury sandstone and features an Australian stripped classical style with Art Deco details.

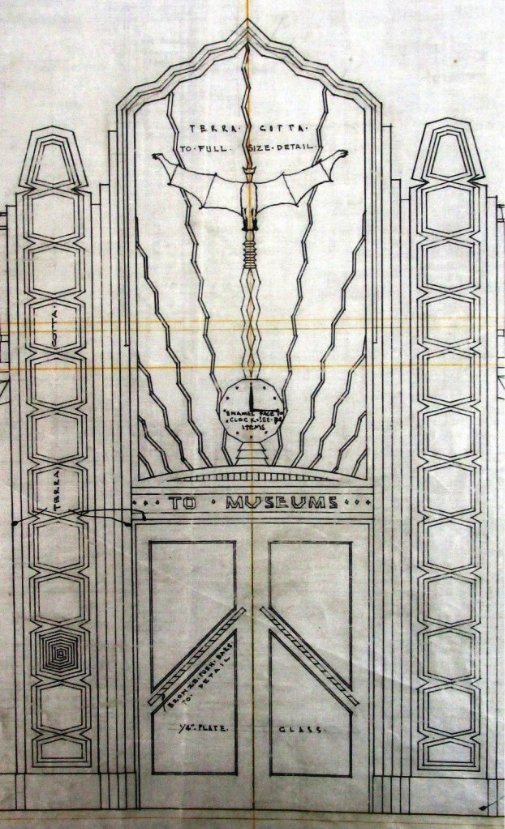

The main façade features a central slightly protruding curved entry portico, which is accessed by a flight of granite steps. Either side of the entrance, the façade is modulated by full height sandstone faced fluted panels and windows. The head of the columns has an engraved panel featuring lizards. Between the panels and windows is a bay of windows at each floor level. The spandrel panels below the windows are decorated with ornate glazed terracotta tiles featuring a deco design.

At each end of the main façade, the walls are modelled with protruding profiled panels of sandstone at the ground floor level and a circular projecting stone at the upper level. This same detail carries through to the side façades, which are generally flush sandstone, with high level steel framed windows (into the galleries).

A large sandstone dish is located on either side of the main entry with a light pole located in the centre. These were originally designed as flower beds.

Some sandstone sills and string courses were replaced in 1986-87 and some patching of sandstone has previously been undertaken.

The sandstone has generally deteriorated with some joints opening up and spalling. This has been investigated and has been recently conserved and protected.

The roof is a flat roof, originally a membrane but with metal roof over the galleries. This was recently repaired. The rainwater heads and downpipes are copper.

There are some lower level windows that provide light on the basement which are of ribbed glass block. Some of the original blocks have been removed and replaced by louvres. There are ventilating holes to the basement on the east and to the upper level on the north and south.

Windows adjacent the main entry include decorative bronze grilles.

Window frames are bronze coloured.

The north and south sides have no ground floor window (as they are a theatre, library and galleries) but the upper windows have internal and external windows with a 200mm gap. The original glass was “tapestry” obscured glass which appears to remain, except for those damaged in the January 2020 hailstorm.

Other elements include a goods hoist installed in 1986-7 to the south side for basement access, a nitrate bunker to the south which is a concrete building with earth mounded on three sides and a concrete and steel balustrade access ramp to the north (infrequently used).

The Annex

The Annex was constructed in 1998. The two-storey building (with plant and services in located in the large basement) has a flat projecting copper roof with copper rainwater heads and downpipes similar to the main building.

Walls are sandstone or sandstone coloured precast concrete. The west side has a pattern of panels and windows with coloured spandrels not unlike the pattern to the east side of the main building. Windows are bronze coloured aluminium. The north and south sides are mainly bronze colour aluminium louvres to plant areas.

The main entry to the west is glazed and includes granite stairs and a granite ramp.

The Residence

The Residence is a two-storey rendered brick cottage with tiled roof. It is generally in quite good condition except for the internal cracking which is quite extensive and damage to the tiled roof due to hail in February 2020. The 2004 advice from John Skurr, structural engineer, made the following comment:

- the overland flow of the surface stormwater was not satisfactory in itself and is also concluded

as the most likely cause of the general cracking in the external and internal brick walls.

b. cracked internal and external brick walls especially in the stairwell area.

c. Floor joist and bearer spans appear to be designed for office loads rather than domestic floor loadings, these proved to be marginally satisfactory.

In 2006 the building was underpinned and drainage around the building improved. The building is externally sound, however internal cracks remain.

The Residence has been used by ANU as a research centre and offices in recent years. This has been achieved without alterations to the plan of

the building.

Externally the building is rendered and painted with stepped detailing to bay windows, main room window and entry. The top of the chimney is also finely detailed. The roof is a hipped terracotta tiled roof with metal gutter and downpipes.

The garage has been converted into a bike shed with a concrete slab floor, asbestos cement ceiling, rough rendered and painted masonry walls. The door is a ledged and braced timber door with D handle.

The laundry now joins with the house and is similarly finished to the residence. It has a painted panelled door with knob handle. The infill to the house includes an electrical distribution board and hot water cylinder.

A woodshed exists adjacent to the garage and is a flat sheeted building with cover strips and a concrete tiled gable roof. The timber door is metal clad.

Other details include a clothesline, brick paving around the house with plastic covered drain and concrete paths that extend to adjacent buildings.

An air conditioning unit is on the east side.

Condition throughout all buildings is reasonable, except for recent hail damage, but internal cracks are extensive and asbestos cement sheeting remains. Rear fly screen is broken.

The main building is in quite good condition especially with the courtyard render repair underway.

The Annex is in quite good condition.

The former residence is in reasonable condition, except for the recent hail damage, although a large number of cracks exist internally.

The NFSA buildings are significant for their original role in housing the Institute of Anatomy. The collection housed became a significant record of Australian fauna and aboriginal life. The Institute also played a role in researching various aspects of national health. The present role, in displaying and interpreting the NFSA audiovisual collection, maintains a high level of national significance for the building.

The setting of the building in an open landscape, the front entrance address to the McCoy Circuit axis and symmetrical planning provides a strong aesthetic appeal to the whole place.

The main building is an outstanding example of inter-war stripped classical with Art Deco detailing comprising a strongly symmetrical plan and elevation treatment. The fenestration has a strong vertical composition, with simply detailed columns. More detailed elements are restricted to spandrel panels and doorways. External detail shows Art Deco influence with a distinctive Australiana character. The interior of the buildings (principally the main building) are fine examples of substantially intact quality Art Deco style interiors.

The NFSA site has strong associational links with significant people involved in its design, development and administration.

Design Architect | > W Hayward Morris. |

Other Architects | > J S Murdoch oversaw design process; |

> E M Henderson design and documentation involvement for interiors & joinery. |

Landscape Designer | > A E Bruce. |

Administrators | > Sir Colin McKenzie, founding director and the driving force in creating the Institute; > Sir John Butters, Chairman FCC had a strong influence on the development of the V shape plan; and > Sir Neville Howse, Minister for Health & Defence at the time was Instrumental in getting Cabinet approval to construct the building. |

The usage of the Innes Bell Hollow Block system in construction of the ground floor is indicative of the use of a technique which was technically advanced for its time. The building is a rare example of the use of this technique which was a predecessor to the modern waffle slab.

The building has strong social links with the community through its original occupancy as the Institute of Anatomy and currently as the headquarters for the National Film and Sound Archive.

The NFSA, its site and buildings are Commonwealth Heritage Listed significant elements of our Australian cultural heritage and retain a high degree of integrity from their original construction. The objective of the following conservation policies is to manage the heritage significance of the place in a manner appropriate to conserve and protect the official listed values and heritage significance associated with the building and site, and thereby its significance. At the same time the building and site need to continue to be used as an archive, exhibition and office facility.

Conservation Objective 1

To ensure that any actions which will impact on the official listed values and heritage significance of the place are in compliance with the EPBC Act, in reference to the Burra Charter and in consultation with professional heritage conservation planning experts.

Policy 1.1

The statement of cultural significance and list of items set out in Section 4.7 should be accepted as the primary basis for future planning work and management of the building and site.

Policy 1.2

The future conservation and development of the NFSA Buildings and site should be carried out in accordance with the EPBC Act and principles of the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance (Burra Charter). Actions to always be consistent with the requirements of the EPBC Act.

Policy 1.3

The policies recommended, and options discussed throughout this document should be endorsed and followed when considering future planning and work associated with the NFSA Buildings and site

Policy 1.4

The principles of protecting and conserving the building to retain the significance and protect official listed values as outlined in Section

4.7 to be adopted.

Policy 1.5

Any potential action that may affect the official listed values of the NFSA need to refer to the EPBC Act and referrals, especially those are that have a low tolerance for change.

Conservation Objective 2

Ensure ongoing use conserves and protects the official listed values and heritage significance of the place and the associated values and meanings.

Policy 2.1

The main building should retain a predominantly exhibition function. Smaller spaces within the building could retain an office, display, storage or meeting function. The residence could be returned to a single residence or continued as office space.

Policy 2.2

The NFSA buildings be conserved, protected and adapted in a manner that does not compromise their official listed values and heritage significance and in a way consistent with the policies set down in this Heritage Management Plan.

Policy 2.3

The displays and resources in the main building are to remain accessible to the public.

Policy 2.4

In order to conserve and protect the official listed values and heritage significance, including the landscape setting, any works (such as site development for roads, car parking and buildings) need to be considered in reference to the EPBC Act with major works needing to be referred to the Minister for Environment.

Policy 2.5

Prepare a landscape plan to guide management of the landscape setting of the place to protect official listed values and heritage significance so that replacement of trees that are posing a danger or require replacement for other reasons and with reference to the EPBC Act.

Conservation Objective 3

To retain the existing and historical forms, details and character of the place and significant elements while allowing ongoing effective use as conference/meeting venue. Changes to the buildings and site can be permitted if essential for the ongoing conservation for the place provided the impact on official listed values and heritage significance as per the EPBC Act is nil or minimal.

Policy 3.1

An additional building on the site could be permitted provided it does not affect the official listed values and heritage significance of the site and it meets the requirements of the EPBC Act.

Policy 3.2

Further extensions and alterations to the main building are not supported.

Policy 3.3

Further extensions and alterations to the residence are not supported.

Policy 3.4

Alterations are to be sympathetic to official listed values and heritage significance and are not to be intrusive.

Policy 3.5

Changes to meet statutory requirements as defined by the National Construction Code Volume 1 (Building Code of Australia), Australian Standards or Authorities shall be considered in the context of the Policies 3.4, 4.1 4.3.

Policy 3.6

Repairs and maintenance are essential to heritage conservation and will ensure ongoing conservation and protection of the official listed values and heritage significance.

Conservation Objective 4

With reference to the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter and the EPBC Act, ensure the proper conservation and protection of the official listed values and heritage significance of the NFSA and site, where the various components contributing to its cultural significance are maintained and interpreted.

Policy 4.1

Items of exceptional significance (official listed values) are to be conserved and protected including through monitoring.

Policy 4.2

Items of considerable significance are to be conserved and protected. Intervention in the items or fabric can occur as long as it complies with the EPBC Act and in reference to the Burra Charter and protects official listed values.

Policy 4.3

Items not official listed elements or the items of lower significance, such as those of moderate or some significance in clause 4.7 should be retained but could be altered, removed, adapted or remodelled to allow for the conservation of elements of greater significance, or for operational requirements but only after consideration

of alternatives that minimise any intervention or impact and

appropriate recording. Any actions will need to comply with EPBC ACT.

Policy 4.4

The items considered intrusive in Clause 4.7 can be removed at any time, subject to advice from a heritage specialist and photographic recording.

Conservation Objective 5

Ensure processes are in place to record the place before change occurs to maintain an historical record.

Policy 5.1

Original details and finishes must be recorded prior to any major refurbishment or modification. Recording should be undertaken by a heritage specialist and the record retained by the NFSA and included in reports to the Minister in accordance with the EPBC Act.

Conservation Objective 6

To provide a management framework that includes reference to any statutory requirements and agency mechanisms for the conservation and protection of the official listed values and heritage significance of the place.

Policy 6.1

Existing registers be updated with the details contained within this report.

Policy 6.2

In accordance with the EPBC Act the HMP must be reviewed within every 5-year period. The review is to check that no new material is to hand, to review and change details as may be required and to reconfirm policies.

Policy 6.3

A clear management structure and system needs to be maintained by NFSA to ensure works occur in a correct way, and Conservation Policies are applied.

Policy 6.4

Interpretation of the site should be promoted in accordance with the Interpretation Plan.

Policy 6.5

A furniture study be undertaken to identify all items of loose furniture that were part of the original Institute of Anatomy. The furniture is to be conserved and protected and used within the existing building in conjunction with the NFSA collection management policy.

Policy 6.6

All original documentation for the building should be retained by the National Archives of Australia (NAA) and NFSA.

Policy 6.7

Procedures for divestment (in accordance with the EPBC Act), sale or lease of the property must consider potential impact on official listed values and heritage significance and put in place methods to conserve and protect heritage significance and be referred to the Minister for the Environment.

Policy 6.8

Access to the building needs to be controlled so the collection is not placed under threat or concern.

Policy 6.9

Sensitive material to be identified and access to it controlled by management policies.

Policy 6.10

Stakeholder consultation to occur as per EPBC Act. Additional consultation with stakeholders or interested groups can occur at the discretion of the NFSA.

Policy 6.11

Management of sensitive information to be implemented in ways that are not inconsistent with the EPBC Act.

Policy 6.12

Unforeseen discoveries or disturbances require special attention.

Policy 6.13

Professional conservation advice to be sought when necessary.

The NFSA is responsible for overseeing works carried out to all properties in their ownership including those demonstrating official listed values. This includes funding, review and monitoring the HMP and conservation works. Future works and enhancement works will need to meet EPBC Act requirements. Ongoing and regular maintenance is required.

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) requires that a Heritage Management Plan (HMP) should be prepared for all assets on the National and Commonwealth Heritage Register and that they be updated within every 5 years.

The National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) commissioned this update to check that no new material is to hand, to review and change details as may be required and reconfirm policies. As a separate exercise the NFSA also commissioned an update of the Heritage Strategy.

Since the previous HMP the Theatrette has been refurbished, the South Gallery has re-opened for public exhibitions, the Library and Front Room have been re-purposed for public programs or exhibitions, the Director’s Residence has been leased to the Australian National University (ANU) and conservation of stonework is underway.

1995 Conservation Plan Volumes 1 - 3, Philip Cox Richardson & Partners Pty Ltd

2009 Heritage Management Plan, Eric Martin & Associates

The National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) requires the Heritage Management Plan to be reviewed in accordance with Policy 6.2 of the existing plan.

“The Heritage Management Plan must be reviewed within every

5-year period. The review is to check that no new material is to hand, to review and change details as may be required and to reconfirm policies.”

The methodology is based on the methods set out in JS Kerr The Conservation Plan, Australia ICOMOS guides and technical notes and the Environment Biodiversity and Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) requirements.

It includes:

> Update and expansion of documentary evidence and bring it up to date to 2020.

> Detailed inspection of the building to update the description and condition which will also benefit from work, maintenance records and reports undertaken since the last HMP.

> Reassess the significance through a comparative analysis, assessment against criteria and a review of the statement of significance.

> Preparation of detailed opportunities and constrains arising from the statement of significance, NFSA requirements, statutory controls, regulations and other stakeholders.

> Preparation of detailed conservation policies and explanation of what they mean to NFSA and then establish the management required for ongoing conservation of facilities. This will establish and define the requirements of the schedules in the EPBC Act and provide a practical basis for ongoing management and a schedule of works in priority order.

The assessment includes the site, landscape, buildings and relevant details and considers the past HMPs and Heritage Strategy.

The draft document went out for public review before being finalised.

The public consultation included:

> Notice to Friends of the NFSA;

> Letters to National Trust of Australia (ACT) and Australian Institute of Architects; and

> Advertisement in the Canberra Times and The Australian.

3 Friends of the NFSA requested copies.

No comments were received.

This HMP has been prepared by:

Conservation Architects | Eric Martin & Associates | Eric Martin AM |

| | Bronwynne Jones |

Historian | | Dr Brendan O’Keefe |

Landscape Architect | Redbox | David Moyle |

Archaeologist | DiPetaia Research | Dr Peter Dowling |

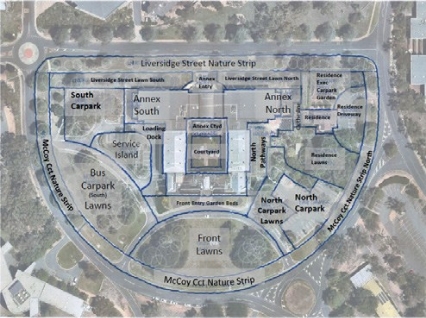

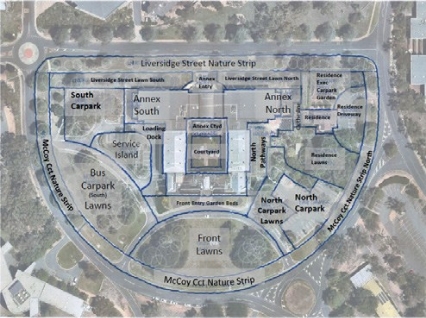

The study area includes the whole block bordered by Liversidge Street and McCoy Circuit, Acton (refer Figure 1). The area includes the NFSA main building and Annex, the residence, and the associated roads, parking, paths and landscape.

Figure 1: Location Plan, 2018 (Google Earth 2018)

NFSA is situated on Designated Land. This is Territory land in the ACT where the National Capital Authority exercises planning control. It is recognised with the following listings heritage listings:

> Institute of Anatomy (former) McCoy Cct, ACTON ACT, Commonwealth Heritage List, Place No 105351 22 June 2004.1

> Institute of Anatomy (former) McCoy Cct, ACTON ACT, Register of the National Estate, Place ID 13261 dated 21 October 1980 (note this register is no longer active).2

> National Film and Sound Archive (Australian Institute of Anatomy), The Australian Institute of Architects, listing dated 9 October 2010.3

> Institute of Anatomy/National Film and Sound Archive, National Trust Register of Classified Places1981.4

The Main Building was removed from the ACT Heritage List as the National Capital Authority (NCA) has planning control.

The condition report is general and does not include a room by room detail and references other reports. Condition assessment was limited to a visual inspection.

The HMP considers the building and setting only and does not consider the Institute of Anatomy collection that existed in the building or the current NFSA collection which is managed under the NFSA Act and relevant collection management policies.

The access to information, the site and previous details has been greatly assisted by Craig Revell of NFSA whose assistance and cooperation has been greatly appreciated. Other NFSA officers assisted in providing access and information which is also appreciated.

Archaeological investigations in the ACT have revealed a Pleistocene antiquity of Indigenous occupation in the Southern Highlands of Eastern Australia, centring on the Murrumbidgee River and tributaries. Excavations at Birrigai rock shelter in Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve have produced evidence for relatively discrete phases of occupation of the shelter dating to back to c.25,000 BP5. A first phase of occupation beginning in c.25,000 BP was of low intensity use of the site which was maintained through to c.3,000 BP when occupational intensity increases dramatically. This increase in Indigenous occupation is reflected in many other places in the southern highlands. Around c.100 BP the evidence for occupation, such as charcoal from fires and artefact density, decreases. This period sees the onset of European impact on the landscape and the subsequent impacts on Indigenous cultural and economic practices.

The archaeological investigation at the Birrigai Rock Shelter has therefore revealed a deep antiquity for human use of this area of the highlands and more specifically to the Canberra region. It should be noted, however, that the c.25,000 BP date should not be seen as the earliest arrival of Indigenous people into the ACT region but as the earliest radio-carbon date so

far obtained in an archaeological sequence. The actual antiquity of human occupation in the area almost certainly goes back to a much earlier time.

Apart from Josephine Flood’s work in the 1980s, recent excavations at sites in the Namadgi Ranges of the ACT6 and theses by several ANU students, there has been little detailed archaeological research undertaken in the ACT. Our knowledge of the period from the Pleistocene to European arrival is sparse. Most subsequent archaeological work in the ACT has been development driven, consisting mainly of non-intrusive surface surveys. The results have, however, revealed many areas, especially in the lower valleys, that have great research potential. This knowledge vacuum is an extraordinary situation, given the known antiquity of human occupation and the scope for further rigorous scientific investigation. Additionally, the ACT has some of the most important wetland areas in Australia that can provide invaluable data regarding the palaeoecology of the region.7

Information derived from existing radio-carbon dates of cultural deposits dating to the early to mid-Holocene have provided some evidence that people were active in the high country during the last 9,000 to 6,000 years when climatic conditions were suitable for a hunter-gatherer economy.

An increase in active occupation and use of the area appears to have peaked at around 2,000 BP. But recent excavations have revealed, an apparent decrease in cultural evidence dating to between 4,500 and 2,000 BP, which is in contrast to major population shifts seen in other archaeological sites in southeast Australia. Whether this reflects an actual behavioural trend uniquely relating to the highland areas of the ACT is still unclear and will require further investigation.8

But, notwithstanding the need for more research, it can be reliably assumed that the National Film and Sound Archive is located on the traditional lands of the Indigenous people who have inhabited this area for at least 25,000 years. Their descendants continue to live in Canberra and the surrounding region and consider it their ancestral Country. Cultural, historical and archaeological evidence suggests that the Canberra region was an area traversed and occupied by several socio-linguistic groups (Ngarigo, Ngambri, Ngunnawal, Ngunawal, Walgalu) and an important place for meetings and ceremonies. This concept is today firmly held by the living descendants of the Indigenous groups and contributes to the foundation of their current cultural history and beliefs.

5 Flood, J., Magee, D. & English, B. 1987, ‘Birrigai: a Pleistocene site in the south-eastern highlands, Archaeology in Oceania, 22:9-26; Flood, J. 2010 Moth Hunters of the Australian Capital Territory, J.M. Flood, Canberra; Theden-Ringl. F., 2016 ‘Aboriginal presence in the high country: new dates from the Namadgi Rangers in the Australian Capital Territory, Australian Archaeology, Vol 82:1 pp. 25-42, (http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs

/10.1080/03122417.2016.1163955 accessed January 2018),

6 Theden-Ringl, ibid.

7 Brockwell, S. & Dowling, P., The Archaeology of the Australian Capital Territory. A strategic region for understanding cultural and natural landscapes in south eastern Australia over the last 20,000 years, paper delivered at the Australian Archaeological Association conference, 2010.

8 Theden-Ringl, 2016, ibid.

A 2013 review of ethnographic, linguistic and historical sources relating to traditional Aboriginal associations to Country for the broader ACT region, concluded that,

the Canberra area before European settlement would have had highly complex systems of associations with the land found elsewhere in Australia but that those systems broke down early in the colonial historical piece. It is clear that

the combined effects of massive demographic stress, alienation from country, forced adjustments and necessary engagements with European settlers led to an early breakdown of original relationships to land and landed identity.9

In 2012 a heritage study of the ANU campus consulted the Representative Aboriginal Organisations (RAOs)

on the cultural significance of the campus and wider areas along the Molonglo River corridor (Lake Burley Griffin), Sullivans Creek corridor and Black Mountain. Although the NFSA boundary is outside the ANU campus area it is immediately adjacent

and intimately connected with the natural and Aboriginal cultural landscape.10

The following observations about the ANU campus and surrounding area were made by the individual representatives from the ACT’s

RAOs and included in the heritage study. Most observations were made independently between the groups, indicating a generally held common understanding of the place. Some observations have been paraphrased and abbreviated due to the sensitive nature of the material provided

by some of the representatives.

The meanings and values associated with the material have not been changed. Parts of the ANU campus with cultural significance include:

- The biodiversity corridor along Sullivans Creek and into Acton Ridge is important. It reflects the fact that Sullivans Creek was an important water course and resource zone that will have contributed to the attractiveness of the place as a meeting area. The conservation of this zone is considered important.

- The whole of the campus is significant due to the high usage of the area by Aboriginal people prior to the arrival of Europeans. It was part of a well-used zone for meetings and trading and was located in close proximity to important ceremonial areas, including the corroboree site near the entrance to the Botanic Gardens. The intensity of use of the area is attested to by the historical observations about the number of campfires along Sullivans Creek.

- Despite its recent modification, Sullivans Creek itself is identified as a feature that embodies the significance of the campus as a meeting place as well as a resource-rich zone. The conservation of this feature is important. The rehabilitation of the northern section of this waterway for natural water filtering is also considered to be an important proposal.

- Acton Ridge is part of a track that connected a series of important landmarks: Mount Rogers, Black Mountain and Capital Hill—the latter being a sacred site.

- Surrounding features with associative cultural significance:

> Black Mountain is an important landscape feature with connections to other landscape features.

– In particular the connection between Mount Rogers, Black Mountain and Capital Hill is very important.

– Black Mountain with Mount Ainslie formed a pair of landmarks also used for navigation and landscape recognition. They were seen as being representative of women’s breasts.

> More than one corroboree site was identified during this process: one where the entrance to the Botanic Gardens now stands (noted above), one just to the south of Black Mountain Drive and one further to the south, now submerged under the lake. None of these are directly affected by works on campus.

> Black Mountain was part of a longer and more substantial walking/tracking route up the east coast of Australia. Now parts of that walking track have been incorporated into the ‘National Trail’.

Archaeological evidence has shown that the Molonglo River, Ginninderra Creek and Murrumbidgee River corridors were important Indigenous resource zones that attracted a considerable level of hunter-gatherer occupation. The importance of these zones has been demonstrated by archaeological surveys where several hundred Aboriginal sites including open camps sites, stone quarries, scarred trees and ceremonial sites have been recorded. The proliferation of stone artefact sites, their geographical locations and densities have indicated that human activities were focused on the gentle slopes, spurs and alluvial flats bordering the riverine corridors where access to water and food sources were readily available. The NFSA site, is located in such an area on high ground above the former Molonglo River and would have been a focal area of subsistence activities and movement for several millennia.

9 Kwok, N. Considering Traditional Aboriginal Affilliations in the ACT Region, draft report to Australian Capital territory Government, Canberra, 2013, (http://www.cmd.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1031698/Documents.pdf, accessed 31 January, 2018).

10 Godden Mackay Logan, 2012, ANU Heritage Study Acton Campus, vol 1, Report prepared for The Australian National University.

An archaeological assessment of the Murrumbidgee River Corridor within the ACT was undertaken in the early 1980s.11 The general survey findings indicated that there were Aboriginal sites throughout the Murrumbidgee corridor environment, with both riverine and non-riverine oriented economic activities being reflected. However, the survey showed a strong positive association between the concentrations of sites with distance from water sources. Higher concentrations of sites were common in close proximity to water sources (for example the Murrumbidgee and Molonglo Rivers). Such an association is indicative of a high economic exploitation of resources within river valleys and permanent water sources.

In 1919, on a visit to the site of the new Australian Capital, Henry Percival Moss, the Commonwealth Chief Electrical Engineer, found a stone axe head in the vicinity ‘quite close to the Acton offices. In 1925 an examination of the surface

of a ‘sandy ridge’ between Old Parliament House and the Molonglo River resulted in the discovery and collection of several stone scrapers and points. At around the same time another axe head was located during the laying out of the laws in front of Old Parliament House. During 1929 and 1930 and succeeding years Moss made several surveys of the City and Acton areas. He identified particular areas of focal occupation along the Molonglo corridor:

> The site of the Institute of Anatomy and the peninsula running from it around to Lenox Crossing near the Acton offices.

> The long sandy spur running down from Black Mountain towards the Forestry School.

> The western slopes of Mount Russell or Mount Pleasant at Duntroon and possibly the eastern slopes also, which have been built over since 1911.

> An area between Duntroon and Scott’s Crossing on the north bank of the Molonglo.

> An area between Scott’s Crossing and Lennox Crossing including the area around Provisional Parliament

House (now the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House).12

Moss continues:

[In 1931 and 1932 the area bounded by the Institute of Anatomy and Sullivan’s Creek and the Hospital yielded a large grinding stone and two pounding stones. This grinding stone is well adapted for resting on a man’s knees while he sharpens the edge of an axe or other tool.

One or two chips were also found and during the same period Mr. Kinsella, of Sydney, found a fine axe-head in the same locality.13

Moss collected over 300 stone artefacts in the area now defined as Acton and Canberra City, some of which were first exhibited in the Institute of Anatomy and then later formed the Moss collection of stone artefacts at the National Museum of Australia. Moss concludes that:

While much material was collected on ridges exposed to the four winds of heaven as well as the blasting heat of summer and the freezing cold of winter, a considerable amount was recovered from depths ranging from two or three to six feet [0.6 or 0.9 to 1.8 metres] below the surface and had thus been protected against weathering.14

> Sullivans Creek 1: a corroboree site recorded in the Canberra Archaeological Society database from information provided by Bluett in 1954. The site is listed as destroyed, but location data indicates that it was close to the lower reaches of Sullivans Creek.

> Institute of Anatomy Site: a hatchet found in 1934 by Kinsela. The location of this artefact was recorded as 100m west of the Institute of Anatomy, near Sullivans Creek. The details of the location are unknown, but it is considered to have been destroyed.15

Sites on the eastern side of Black Mountain:

> BM1: Isolated artefact recorded in 1985 (no description details) located just off Black Mountain Drive.

> BM2: Artefact scatter comprising three artefacts also recorded

in 1985 (no description details). Located on a small terrace on a ridge running down the eastern side of Black Mountain towards the southern end of Sullivans Creek.

> BM3: Isolated artefact recorded in 1985 (no description details) but located nearby on the same ridge as BM2.

> BM4: Artefact scatter and Potential Archaeological Deposit (PAD) recorded in 1985.

Comprises 19 artefacts, including quartz, quartzite, and chert pieces. Artefact types include

two cores and the rest flakes.

> BM5: Scarred tree of probable Aboriginal origin in 1995.38 Located up the northern side of Black Mountain to the west of CSIRO.

11 Barz, R.K & Winston-Gregson 1981 Murrumbidgee River Corridor. An Archaeological Survey for the NCDC, National Capital Development Commission, Canberra (unpublished report ACT Heritage Library).

12 H.P. Moss, ‘Evidences of Stone Age occupation of the Australian Capital Territory’, Report of the Twenty-Fourth Meeting of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, 1939, pp. 163-166.

13 Ibid, p. 164.

14 Ibid, p. 165.

15 Godden Mackay Logan, 2012.

> BMF9: Isolated artefact recoded in 2003.39 No description details provided. Located to the west

of BM5.16

Vicinity of the International Sculpture Park and Old Canberra House:

> Black chert core recorded in 2018

– well worked, 38.5 x 29.5 x 19.5

with 20% remaining.

> Silcrete flake recorded in 2018

– retouched edge.

Both these artefacts were located at the base of a slope which has undergone extensive erosion of the topsoil.17

ANU Campus:

> 5 scarred trees situated throughout the campus.

The land on which the Institute of Anatomy was eventually built formed part of the first European settlement of the Canberra district. In late 1823, stockmen employed by Joshua John Moore, a clerk to the Judge-Advocate in Sydney, arrived in the district with a herd of cattle and occupied a tract of land between Mount Ainslie, Black Mountain and the Molonglo River. The stockmen erected huts and stockyards on the land, specifically on the site of what later became the Royal Canberra Hospital. In October 1824, Moore obtained a ticket of occupation for the land and just over two years later took up an option to purchase an estate amounting to 1,000 acres. During the 1830s, Moore had a cottage erected on the property – also on the later site of the hospital – even though he did not reside there.

The economic depression of the early 1840s seriously damaged Moore’s financial position, forcing him to sell his ‘Canberry’ property in 1843. The purchaser was Lieutenant Arthur Jeffreys, an officer of the Royal Navy who married one of the daughters of Robert Campbell of Duntroon. Jeffreys named the property ‘Acton’ and, although he and his descendants did not live there, the Jeffreys family was to retain ownership of the land for almost eighty years. Arthur Jeffreys himself leased the cottage on the property to the Church of England, which used the building as its local rectory. This arrangement continued until 1873 when the Church erected a new rectory building. The Jeffreys family then leased the property to Arthur Brassey who used the property as a grazing run. Brassey remained in occupation right up until the Commonwealth resumed the land for the federal capital in 1911, giving Brassey the dubious distinction of becoming the first grazier to be displaced by the government’s acquisition of the Federal Capital Territory. The resumption was contested by the Jeffreys family, but the dispute was settled in November 1912.18

Preparations, meanwhile, were being made for the establishment of the new federal capital. In May 1912, Walter Burley Griffin’s scheme had been chosen as the winner of the design competition for the proposed city. In Griffin’s design, the site on which the Institute of Anatomy would later be built lay on the eastern extremity of the area designated for the city’s university. Although the original plan showed a building on the site, the proposed structure was merely an unnamed component of the university complex.

The subsequent departmental plan for the city, drawn up after criticisms of Griffin’s design, moved the site of the university eastward, placing the future location of the Institute of Anatomy near the city’s hospital. In the event, this plan was overturned by Griffin’s modification of his original design. This ‘preliminary’ plan restored the university quarter of the city to its original location and displayed McCoy Circuit in much its present shape and location. This plan, which became the working design for the city, showed the centre of McCoy Circuit occupied by an unnamed building which again formed part of the university group.19

The driving force behind the establishment of the Australian Institute of Anatomy was Dr (later Professor Sir) William Colin MacKenzie, known as Colin. MacKenzie had been born of Scottish immigrant parents at Kilmore north of Melbourne in 1877. He later studied medicine at the University of Melbourne, graduating in 1898. A year after his graduation, he became the senior resident medical officer at the Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, a position he was to hold for two years. It was probably during this time that he first developed the interest in childhood diseases that would later play a significant part in the setting up of the Institute of Anatomy. Leaving the Children’s Hospital at the end of 1901, MacKenzie entered private practice as a general practitioner and, at the same time, obtained an appointment as an honorary demonstrator in anatomy at the University of Melbourne.20

16 Ibid

17 Brett Chalmers,2018. ANU Aboriginal heritage Assessment Sullivans Creek & Heritage Trail, report prepared for ANU Heritage.

18 L.F. Fitzhardinge, ‘Old Canberra and district 1820-1910’, in H.L. White (ed.), Canberra: A Nation’s Capital, Canberra, ANZAAS, 1954, pp. 16, 29; L.F. Fitzhardinge, Old Canberra and the Search for a Capital, Canberra, CDHS, 1975, pp. 4-5; Lyall Gillespie, Canberra 1820-1913, Canberra, AGPS, 1991, pp. 8-9, 17, 21, 39, 266.

19 Gillespie, Canberra 1820-1913, pp. 278, 280, 289-90, plates 19, 24, 25; facsimile of Walter Burley Griffin’s design for federal capital, 1911, Clareville Press, Torrens, ACT.

20 Anon., ‘MacKenzie, Sir William Colin’, Australian Encyclopaedia, Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1958, vol. 5, pp. 434-5; Monica MacCallum, ‘MacKenzie, Sir William Colin’, Australian Dictionary of Biography [hereafter ADB], vol. 10, p. 306.

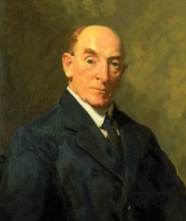

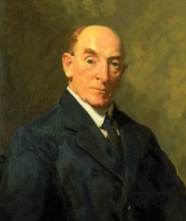

Figure 2: Professor Sir Colin MacKenzie by William B. McInnes, 1928–1938 (National Museum of Australia)

According to MacKenzie’s own testimony, the origins of the Institute of Anatomy lay in the epidemic of infantile paralysis that afflicted Melbourne in 1908. Infantile paralysis was the classical form of poliomyelitis in which the virus invaded the spinal cord and caused weakness, paralysis and wasting of muscles, often with resulting deformity.; During a visit to Britain and the Continent in 1903–4, MacKenzie had studied orthopaedics, the treatment of deformities arising from disease or injury of the bones and joints. With the outbreak of the 1908 poliomyelitis epidemic, MacKenzie found his orthopaedic skills in demand from patients who wanted effective treatment. Basing his work on methods he had learned both in Australia and overseas, he gradually evolved his own unique technique for treating the disease. The treatment involved making use of the patient’s remaining muscle power to promote movement and minimise deformity.21

In the course of his clinical work, MacKenzie began to develop his own idiosyncratic theories about the scientific basis of muscle function and pathology. In his view, the pathological changes to tissue seen in such diseases as poliomyelitis could not be understood by comparison with tissue samples taken from humans who were apparently undiseased. This was because the human race, according to MacKenzie, had been physically corrupted ‘over centuries’ by alcohol, syphilis and other poisons, to such an extent that one could not reliably obtain from any one individual a sample of normal, pristine tissue. In like manner, valid comparisons could not be made with so-called ‘normal’ tissue from commonly-used laboratory animals – dogs, rabbits and guinea pigs – because they had been so denaturalised by domestication. MacKenzie believed instead that the complexities of the human body, and especially muscle function, could only be properly understood by studying the relevant anatomical parts in their simplest and purest form. Such parts were only to be found among the native Australian mammals which had lived in a natural, unpolluted environment for millions of years. As MacKenzie saw it, these mammals were the ‘key animals of the world’ in their potential for playing a crucial role in the solution of human muscle problems. From these somewhat esoteric beliefs, the Institute of Anatomy was later to acquire its distinctive architectural embellishments of figures of Australian fauna.22

As MacKenzie also believed that the native Australian mammals were doomed to extinction within a very short time, he began to assemble from 1912 a massive collection of dissected specimens of these animals. When war broke out in 1914, according to his own account, he realised that his collection could be of benefit to the treatment and rehabilitation of wounded soldiers. At the instigation of the distinguished Scottish anatomist, Sir Arthur Keith, MacKenzie decided to transfer his vast and unique collection to the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in England. The material was despatched overseas in 80 tins and eight tanks. MacKenzie himself proceeded to England in 1915, where he remained for approximately three years. During this time, he helped Keith catalogue specimens of war wounds and assisted in the editing and publication of textbooks on surgical anatomy and muscle function.23

On his return to Melbourne in 1918, MacKenzie was determined to carry on with his orthopaedic work and with collecting specimens of native Australian mammals. As there was no space available for him at the University of Melbourne, he purchased an eleven-room house at 612 St Kilda Road and rapidly began to fill it with his dissected specimens. Soon afterwards, in 1920, he obtained at a peppercorn rental from the Victorian government. This was a lease on an 80-acre tract of land at Badger Creek, Healesville, where he established a reserve for, as he put it, ‘live specimens’. The reserve is still in existence. MacKenzie formally registered the St Kilda Road property and the Badger Creek reserve under the title of ‘The Australian Institute of Anatomical Research’.24

21 Professor Sir W. Colin MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume of the History of Australian Institute of Anatomy, Canberra’, c. 1930, Commonwealth Record Series [hereafter CRS] A2644, item 70; MacCallum, ADB, vol. 10, p. 306; A.J. Proust, ‘Sir Colin MacKenzie and the Institute of Anatomy’, Medical Journal of Australia [hereafter MJA], 4 July 1994, pp. 60-1.

22 MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works [hereafter PWC], ‘Report together with Minutes of Evidence relating to the Proposed Construction of Buildings and Formation of Reservation at Canberra for the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, p. iii.

23 MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; PWC, ‘Report … relating to the Proposed Construction of … the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, p. iii; Australian Encyclopaedia, vol. 5, p. 435.

24 MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; PWC, ‘Report … relating to the Proposed Construction of … the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, p. iii; Australian Encyclopaedia, vol. 5, p. 435; MacCallum, ADB, vol. 10, p. 307.

In the ensuing years, MacKenzie received offers for his collection of dissections from overseas museums, including at least one substantial offer from an American institution. He refused, hoping instead that the Australian government would acquire his collection for the nation. It appears that, during the early 1920s, MacKenzie pressed the government to take this course of action, possibly using the overseas offers as a lever on the federal authorities. Whatever the case, by late 1922 the government had agreed, at least privately, to acquire the collection; the decision was announced prematurely in the British Medical Journal in January 1923. The Australian government duly announced its intentions in March, stating that it deplored the fact ‘that the Commonwealth had no central museum of specimens of its own’ and ‘that it would be wise before already rare specimens became extinct to secure specimens of them for such a collection …’ MacKenzie formally donated his collection to the nation, by way of the Minister for Home and Territories, Senator George Pearce, in June 1923.25

The donation came with conditions. Under the terms of the agreement with MacKenzie (dated August 1924), the Commonwealth undertook to erect buildings and enclosures in Canberra to house his collection of animals, both live and dead. For this purpose, it agreed to reserve one or more sites in the new federal capital. For the first three years from the date of the agreement – that is, until August 1927 – MacKenzie agreed to maintain the collections in Melbourne at his own expense; thereafter, all costs were to be met by the federal government. MacKenzie himself was to be appointed Director of the proposed museum, with the title of ‘Professor of Comparative Anatomy’ and an annual salary of

£600. He took up the appointment on 1 January 1924, preceding by eight months the formal signing of the agreement with the Commonwealth. On his becoming Director of the museum, MacKenzie was compelled to relinquish his lucrative orthopaedic practice in Melbourne.26

It seems quite certain that, in making the agreement with MacKenzie, the federal government did not fully comprehend or foresee what it was committing itself to. Clearly, the government expected that, by the end of the three-year period stipulated in the agreement, it would have buildings ready in Canberra for MacKenzie to occupy, although this was not actually what the agreement specified.27

Unfortunately, MacKenzie also interpreted the agreement in this way, a fact that later led to friction between himself and the government. As it was, the government was not well-placed in the period 1924-27 to erect a major museum building in Canberra or, for that matter, anywhere else. With its commitment to transferring the seat of power to the new federal territory, the government was already heavily engaged in a major building program in Canberra, notably the construction of Parliament House. Funds and labour were not readily available for the building of the proposed museum. The scale of the project, moreover, was rather greater than it first appeared, involving not just the construction of a museum building, but the erection of residences for MacKenzie and his staff who were to accompany him from Melbourne. In addition, it included the laying out of a sizeable reserve for his live specimens, complete with animal houses, enclosures and ponds of various kinds. The whole project promised to be quite an expensive undertaking.

It may be asked why the government decided to take on a task of this magnitude at such an inconvenient time. Certainly, the threatened loss overseas of a unique and irreplaceable collection of specimens of Australian fauna was a powerful motivating factor in the government’s initially agreeing to acquire and house MacKenzie’s collection. Indeed, the original title of the proposed institution, the ‘National Museum of Australian Zoology’, was probably a reflection of the government’s primary assessment of the collection’s value as a comprehensive assemblage of specimens of Australia’s native animals, as distinct from the collection’s supposed value to research on human health problems.

Beyond that assessment, however, the government had other considerations in mind. For one thing, it wanted to make Canberra not just the country’s administrative capital, but also the national centre for Australian culture, education and science. Virtually at the same time as he agreed on the Commonwealth’s behalf to acquire MacKenzie’s collection, Senator Pearce secured Cabinet approval for the building, at a cost of about £13,000 per annum, of an observatory on Mount Stromlo. The government was already committed to the establishment of a national library in Canberra and, rather more vaguely, to the eventual foundation of a university. With institutions of this character destined for Canberra, it was singularly appropriate that the national capital should also house the nation’s foremost collection of specimens of native animals. As the British Medical Journal pointed out in hailing the government’s decision to establish a museum of Australian zoology, ‘the new Commonwealth Capital at Canberra … will then become the world’s centre for the study of

25 Australian Encyclopaedia, vol. 5, p. 435; MacCallum, ADB, vol. 10, p. 307; minute, MacKenzie to Acting Prime Minister, 5 November 1930; and MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; British Medical Journal, 17 January 1923; information from Monica MacCallum, Dept of the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Melbourne.

26 ‘Zoological Museum Agreement Act 1924’, CRS A6269, item E1/30/51; MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70.

27 Memo, Home and Territories Dept, ‘Article in Melbourne “Age” of 22/7/27, regarding the delay in constructing the buildings for the National Museum of Australian Zoology at Canberra’, 25 February 1927, CRS A431, item 59/450.

Australian fauna.’28

The other main consideration that the government had in mind was the collection’s potential research value in helping to improve the health of Australia’s people. The nation’s health was of unusual concern to the Australian government and to community leaders in this period. This concern was in large measure born of an acute awareness of Australia’s small population and hence of the continent’s vulnerability to foreign invasion. There was a very widespread belief that national security depended on the maintenance of a high standard of health and fitness in the nation’s small population. During the war years, the nation had been shocked by revelations of the extent to which syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases were rampant in the community, and by the generally poor standard of national health revealed in the rejection rate for army recruits.

It was partly as a result of these concerns that the Commonwealth government, in March 1921, had established a federal Department of Health under Dr J.H.L. Cumpston, an individual who was later to have a major influence on the Institute of Anatomy. In 1924, the government also set up a Royal Commission to inquire into the state of the nation’s health. In the meantime, Walter Massy Greene, the Minister for Defence, had added the new health portfolio to his responsibilities, a remarkable combination of ministries that has only ever been repeated once in Australia’s history, and by Sir Neville Howse later in the same decade. The combination was an expression at the highest administrative level of the relationship the government of the day saw between the nation’s health and its security.29

In this climate of anxiety about the health of the Australian people, MacKenzie’s belief in his collection’s value to the understanding and treatment of diseases that particularly affected children was especially welcome. Thus, it is probably highly significant that the person to whom MacKenzie made the offer of his material was Senator Pearce. Pearce had been Minister for Defence for the duration of the war and, much more than most, would have appreciated the need to improve the nation’s health for security reasons. The potential for Mackenzie’s collection to serve this purpose would have not have escaped his attention.

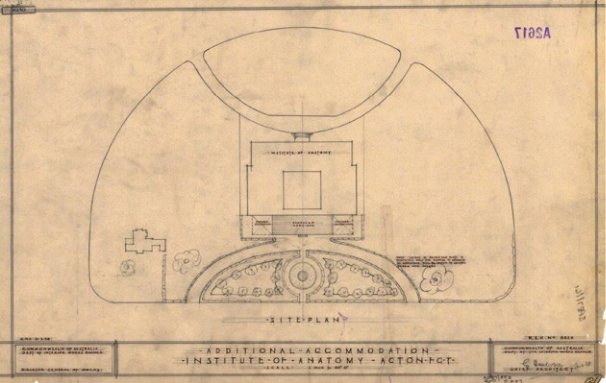

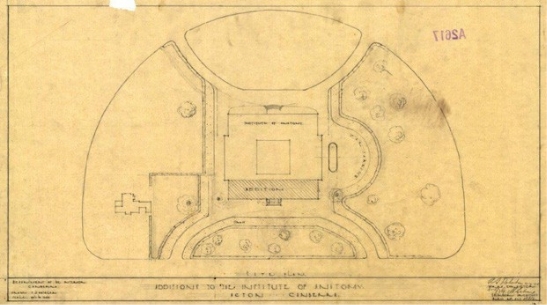

Some time after the Act creating the National Museum of Australian Zoology received formal assent and in October 1924, MacKenzie visited Canberra to select sites for the museum and for the reserve for his live specimens. For the museum, he fixed upon a semicircular plot of land of about 5.75 acres in extent, situated close to the reserve for the city’s proposed university. The choice of location was not accidental: it was envisaged that the zoological museum would eventually form part of the university campus. The selection of a site for a reserve for MacKenzie’s live animals proved a little more problematic, but eventually MacKenzie settled on an 80-acre site about three kilometres west of the city at Westridge on the southern side of the Molonglo. All interested parties had concurred in the selection of both sites by mid-1925, though C.S. Daley, then Acting Secretary of the Federal Capital Commission [FCC], pointed out that Griffin had specified a site for zoological gardens for the city on the northern side of the Molonglo, near proposed

botanical gardens, an aquarium and various museums and galleries. The Commission, nevertheless, had no real objection to MacKenzie establishing another zoo for his own research purposes.30

28 Jim Gibbney, Canberra 1913-1953, Canberra, AGPS, 1988, pp. 73, 159, 167, 258; British Medical Journal, 17 January 1923.

29 Dennis Shoesmith, ‘“Nature’s Law”: the venereal disease debate, Melbourne 1918-19’, ANU Historical Journal, vol. 9, December 1972, pp. 19-23; Michael Roe, ‘The establishment of the Australian Department of Health: its background and significance’, Historical Studies, vol. 17, 1976, pp. 176-92.

30 Minute, C.S. Daley to Secretary, Home and Territories Department, 12 June 1925, CRS A431, item 59/450; PWC, ‘Report … relating to the Proposed Construction of … the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, pp. iv, vi; Second Annual Report of the Federal Capital Commission for the period ended 30th June, 1926, p. 9.

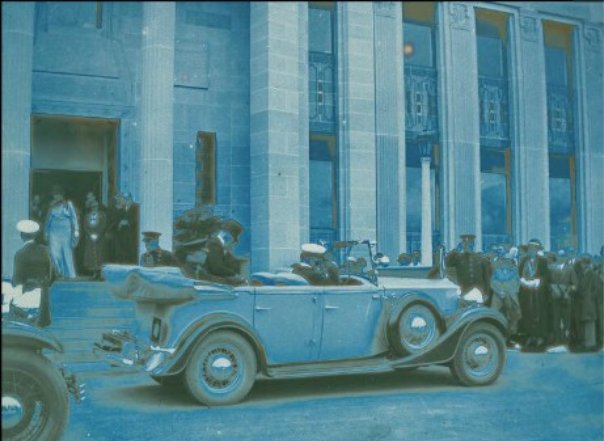

Figure 3: Early site of Institute of Anatomy, Acton, Mildenhall Collection 1901–1948 (National Library of Australia, 2018)

Figure 4: Site of the Institute of Anatomy with notice board for the National Museum, 1927 (National Archives of Australia, 2018)

In July 1925, the Department of Works and Railways was given responsibility for preparing, in consultation with MacKenzie, preliminary plans and cost estimates for the project. MacKenzie himself produced sketch plans in March 1926 for the Department’s architects to work with. A.S. Robertson, a departmental architect, began to work up detailed plans and specifications, completing them by mid-1926. At this point, the Chief Commissioner of the FCC, Sir John Butters, who was probably being pressed by MacKenzie for an early start to the building program, informed the Minister for Home Territories that the FCC could not possibly embark on the work until other more urgent projects had been completed. Taking Butters’s advice, federal Cabinet decided in September to defer work on the museum.31

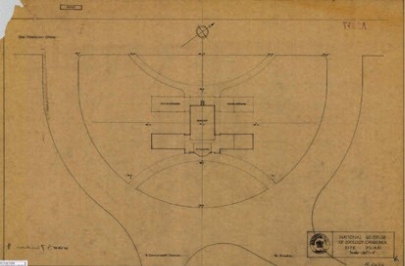

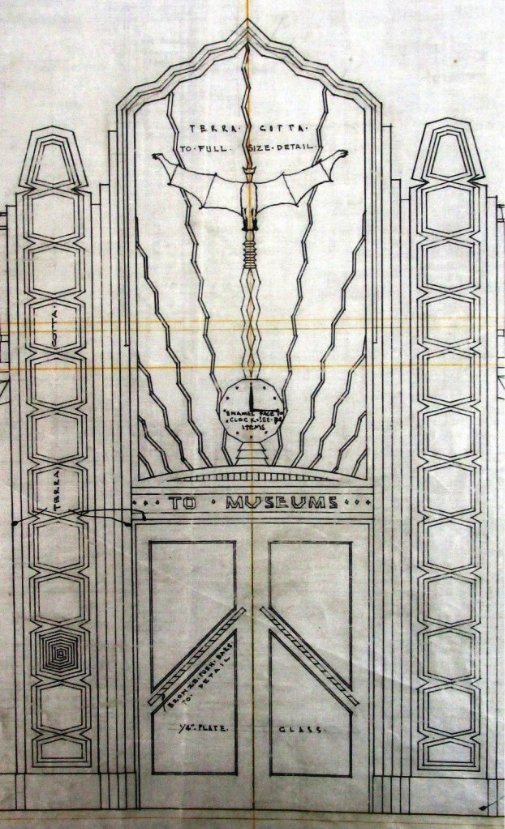

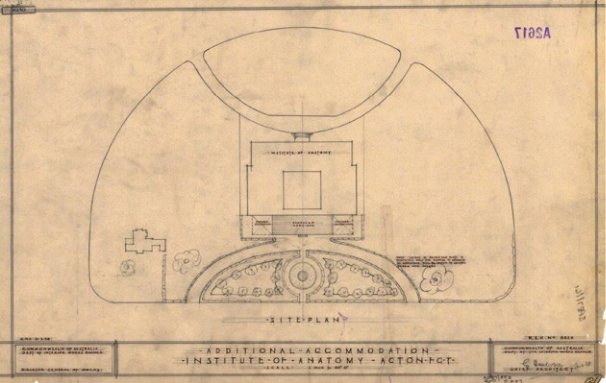

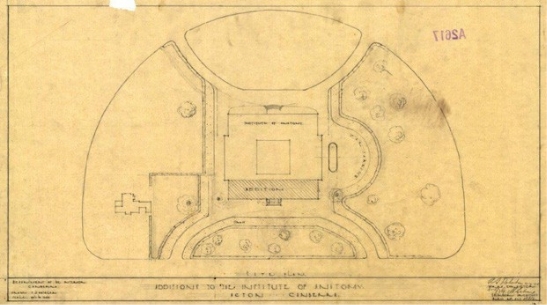

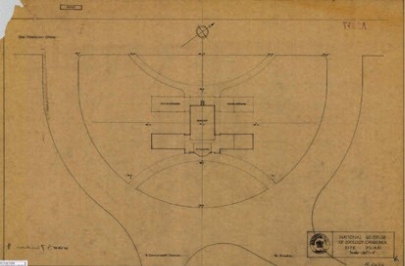

Figure 5: Site plan showing the entrance from both McCoy Circuit and Liversidge Street, 1925 (NFSA 2018)

While Butters was informing the government of the FCC’s inability to start work on the museum,he was also beginning to have misgivings about the design that the Department of Works and Railways had produced for the building. He raised with the Minister for Home and Territories ‘the general question of the policy to be adopted in carrying out buildings such as this, which I hope will be of a somewhat monumental character.’ One way to achieve the character he desired for the building was, as he pointed out to the Minister, to hold a design competition, the sort of approach favoured by the Federal Institute of Architects. But while such competitions had already provided an economic bonanza for certain architects, it had proven a very expensive exercise for the federal government. The alternative was to have government architects prepare the designs for Canberra’s buildings. Butters had no great faith in this method, however, as he believed that there was a ‘danger of monotony’ appearing in the designs.32

Butters soon enlarged on his views before the Public Works Committee. Because the FCC had indicated to the government that it could not even properly consider the current proposals for the museum until April 1927 at the earliest, the government decided as a time- saving measure in February that the Public Works Committee should examine the plans drawn up by Robertson of the Works and Railways Department. Robertson’s scheme was for a single-storey museum building surrounded by a gallery twelve to fifteen feet wide, with an entrance from what is now Liversidge Street. The project was to include a small lecture theatre, and single- storey administration and research blocks were to be placed at the front and sides of the museum building at its McCoy Circuit end, creating a T-shaped complex. There was to be another entrance from McCoy Circuit. The buildings were to be built of brick or concrete, with part of the exterior of the complex faced with ‘some sort of stone’.33

Appearing before the Committee to give evidence, Butters savaged the Works and Railways’ design. He stated that the museum, occupying as it did a dominant position in the city and located near the proposed university, should be ‘of a permanent and impressive character’. He strongly opposed the Works and Railways’ proposal to construct the building in brick and concrete, recommending that the whole building be redesigned ‘to give it a more imposing appearance’. In the face of Butters’s forcefully expressed opinions, the Committee determined on some major design changes for the building. Acting on suggestions put forward by Butters, and with MacKenzie’s concurrence, the Committee recommended that the two wings of the building be

31 Memo, ‘Construction of Buildings for National Museum of Australian Zoology at Canberra. Resumé of Action taken’, February 1927; and minute, J.H. Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, p. 1, CRS A431, item 59/450; memo, A.S. Robertson, ‘Scheme for National Museum of Zoology, Canberra. Notes to Accompany Drawings’, 21 October 1927, CRS A6269, item E1/30/51.

32 Minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘National Museum of Zoology and Zoological Park’, 14 July 1926, CRS A6269, item E1/30/51.

33 Minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, pp. 1-2, CRS A431, item 59/450; PWC, ‘Report … relating to the Proposed Construction of … the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, p. iv.

shortened and made two storeys high. This alteration, the Committee felt, would provide the same floor space at the same cost, but would enhance the design of the structure. The Committee also proposed that the front of the lecture theatre be faced with Fairy Meadow limestone and that the rest of the building be built of high quality Canberra bricks, with base mouldings and other architectural embellishments also rendered in Fairy Meadow limestone. By way of ‘excellent examples’ of what it wished to achieve by this mixture of brickwork and stone, the Committee cited college buildings in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane and even Cardinal Wolsey’s Hampton Court Palace in England. The mixture would also, the Committee hoped, keep costs down. As it was, the total cost estimate for the project, including the development of the animal reserve and the construction of three residences, amounted to £87,080.34

Following the report of the Public Works Committee, Parliament voted unanimously on 24 March 1927 to proceed with the construction of the museum. The FCC, however, was still too heavily engaged in other projects to undertake the work and, as well, did not have on its staff at the time what it considered a ‘first class designing architect’ to draw up the new plans required for the building. Just as significantly, Butters, though he had won some important changes from the Committee, was still far from satisfied with the design. He felt that ‘the layout of the building left much to be desired’ and that ‘a building with only a comparatively small stone feature in the front and the rest of plain brick work was losing a valuable opportunity in Canberra from an architectural point of view.’ Butters was particularly unhappy with the proposed width of the museum (66 feet) and of its surrounding gallery. He wanted both

reduced, but especially the gallery, an alteration that he hoped would allow the ‘objectionable columns’ to be eliminated. The entrances to the museum also bothered him, as he considered that they lacked ‘architectural character’. As an example of the sort of design he had in mind, he put on file an article dealing with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.35

The problem of a lack of a top-class designing architect, as the FCC saw it, was overcome in November 1927 when Walter Hayward Morris, just returned from a visit overseas, was appointed as the FCC’s Principal Assisting Designing Architect. Butters immediately assigned him, as his first job with the Commission, to the museum project. Before the month was out, Morris, armed with the scheme approved by the Public Works Committee and with Butters’s criticisms of it, was dispatched to Melbourne to discuss the new proposals with MacKenzie. MacKenzie readily agreed to Butters’s proposals to reduce the size of the museum and to eliminate one of the two entrances. This latter change, in fact, allowed the inclusion in the design of a small research room, a literature room and a room for the hall attendant. But MacKenzie also proposed some alterations of his own. These were: the provision of a small strong room, a basement workshop, a waiting room next to the Director’s office and an elevator from the basement to the first floor; an increase in the size of the lecture theatre to accommodate an audience of 150 as against 114; the combining of the spaces reserved for the artist and photographer into one room and the creation of a separate dark room; and the omission of all windows and addition of a gallery to the library to allow greater wall space for shelving and to allow for ‘the possibility of lighting from the roof’.

At Morris’s suggestion, MacKenzie later sent him five sketches of Australian animals – the kangaroo, koala, echidna, platypus and reptiles – to serve as models for Art Deco figures that Morris had in mind for the exterior of the building.36

It is extremely likely that Morris’s inspiration to adorn the exterior of the building with fauna and flora figures derived from the Sydney Technical College at Ultimo in Sydney. Built in 1891–93, the building’s exterior featured sandstone sculptures of native Australian animals and plants. The use of such distinctively Australian ornamentations was strongly influenced by the French- born artist Lucien Henry, who was a teacher at the temporary premises the college occupied before the Ultimo building was erected. Henry was a fervent advocate of the incorporation of nationalist elements such as representations of native fauna and flora in local art and architecture.

The actual precedent for ornamenting the exterior of buildings with figures of animals and plants was set by the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London, which opened in 1881. Drawings of the building by its architect, Alfred Waterhouse, had been displayed at the Sydney International Exhibition in 1879 where they excited much local interest and admiration, notably from Henry. When Morris came to design the Institute of Anatomy decades later, he could scarcely have been unaware of the sculptures of Australian animals and plants that graced the exterior of Sydney Technical College as it was, of course, the place where he had studied architecture and where, moreover, he had won the Kemp Memorial Medal named in honour of its architect, William Edmund Kemp.37

34 PWC, ‘Report … relating to the Proposed Construction of … the National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 1927, pp. v, vi, vii.

35 Third Annual Report of the Federal Capital Commission for the Year ended 30th June, 1927, p. 12; MacKenzie, ‘Brief Resume …’, c. 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, p. 2, CRS A431, item 59/450; extract from the Literary Digest, 16 April 1927, on the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in CRS A6269, item E1/30/51.

36 Minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, pp. 2-3, CRS A431, item 59/450; letter, MacKenzie to W. Hayward Morris, 16 July 1928, CRS A6269, item E1/30/51.

37 http://sydneytafe.libguides.com/SydneyTAFEHeritage/ArchitectureDesign ; Joan Kerr, ‘The architecture of scientific Sydney’, Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 118, parts 3 and 4, March 1986, p. 190; Kirsten Orr, ‘The realisation of the Sydney Technical College and Technological Museum, 1878-92: aspects of their cultural significance’, Fabrications, vol. 17, no. 1, 2007, pp. 46-67 (especially pp. 52-4 and 57-60).

While Morris worked on detailed plans and specifications for the revised design, MacKenzie’s patience with the government was wearing thin. In January 1928, he wrote to Howse, who was a Minister without portfolio in the Cabinet and the Australian Army’s former Director of Medical Services in France during World War I. MacKenzie pointed out to him the importance of his research to military medicine and urged the government to get on with the building of the museum. The representations to Howse brought an immediate response. Howse took the matter to Cabinet the same month and secured its approval for the construction of the museum to be given top priority; the FCC was duly instructed to regard the building of the museum as ‘of urgent importance’. Cabinet agreed as well to transfer responsibility for the museum from the Department of Home and Territories to the Department of Health, both of which portfolios Howse was about to take over. The transfer was effected on

1 February. Finally, Cabinet also gave Howse leave to consider a change of name for the institution. It was undoubtedly Howse’s role in getting the project moving that led to the erection of the portrait-in-relief of him that still exists in the southern museum hall.38

Even before the transfer to the Department of Health took place, the need for a change in the institution’s name was becoming evident. Apart from his zoological specimens, MacKenzie was accumulating a substantial collection of Aboriginal skeletal remains. As MacKenzie intended to house this material in his museum, the name ‘Zoological Museum’

was clearly no longer appropriate. In August 1928, MacKenzie and the government signed an agreement changing the name to the ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’. The change was formalised in the Australian Institute of Anatomy Agreement Act of 1931.39

The name change was appropriate for another reason as well. In 1926, the government had acquired the extensive ethnological collection that had been assembled by Dr Horne and his niece Miss Bowie, and soon afterwards had been promised the Edmund Milne ethnological collection of Australian Aboriginal material which was the largest private collection of its type in the world. With the acquisition of these two collections, the Australian government found itself under an obligation to provide proper museum accommodation for them.

This need to house the collections soon became bound up with proposals to establish a National Museum in Canberra. In September 1927, federal Cabinet affirmed the principle of establishing such a museum, but decided not to proceed with it immediately. A year later, a government committee that had been appointed to consider the question of the museum reported that the need for a national museum was, in its opinion, ‘not great’, largely because excellent museums already existed in each of the Australian states. During its deliberations, however, the committee suggested that the Institute of Anatomy might, in time, be constituted as the first unit of the proposed National Museum. In the meantime, there remained the problem of providing suitable accommodation for the Horne-Bowie

and Milne collections. The Institute of Anatomy was an obvious location and, in this way, the building came to be a repository for ethnological material, in addition to its anatomical specimens. It was probably this new ethnological aspect to the Institute’s functions that led to the inclusion of the Aboriginal-style motifs that adorn the exterior of the building.40

Morris completed his plans for the building in mid-1928, at which point Butters submitted them for review, along with the two earlier schemes devised by Robertson and the Public Works Committee, to the Committee of Public Taste. This was a body of five leading Australian architects chaired by G.H. Godsell. On examining the various plans, the committee found that it could not recommend the Robertson or Public Works Committee schemes, but that Morris’s design was acceptable with some alteration. The substance of the desired alteration was the conversion of the building from a T-shaped to a U-shaped structure, with provision for eventually closing in the end of the ‘U’ to create an internal quadrangle. MacKenzie, when told of the proposed alteration, would not agree to it at all, even though the new U-shape would give him two museum halls instead of one. As the Committee of Public Taste would not budge on the issue, Butters organised a meeting involving MacKenzie, Morris and the committee, and here they succeeded in talking MacKenzie around to the idea.41

38 ‘Copy of letter’ (MacKenzie to Sir Neville Howse), January 1928; and minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, p. 2, CRS A431, item 59/450; Cabinet Agenda No. 72, ‘National Museum of Australian Zoology’, 18 January 1928; and letter, Acting Secretary, Dept of Home and Territories to Director General, Dept of Health, 31 January 1928, CRS A1928, item 695/2.

39 Letter, Claude Nevins to MacKenzie, 10 June 1927, CRS A1, item 27/20249; indenture between the Commonwealth of Australia and William Colin MacKenzie, 16 August 1928, CRS A432, item 1931/1837; ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy Agreement Act 1931’, CRS A2863, item 31/44. See also CRS A1, item 29/1896.

40 Dr Helen Wurm, ‘The Institute of Anatomy Ethnological Collections’, address to residential school entitled ‘Canberra – Our National Capital’, ANU, Canberra, 24-30 May 1964, p. 2; minute, MacKenzie to Acting Prime Minister, 5 November 1930, CRS A2644, item 70; Minister for Home and Territories, Cabinet Agenda, ‘Establishment of National Museum at Canberra’, 16 April 1928, CRS A1, item 32/514; ‘Report of Committee of Enquiry appointed to advise on the General Question of a National Museum at Canberra’, October 1928, pp. 2-5, CRS A485, item AJ120/6.

41 ‘Notes taken at the first meeting of the Committee of Public Taste in Sydney’, 1928, CRS A6269, item E1/30/51; minute, Butters to Minister for Home and Territories, ‘Australian Institute of Anatomy’, 14 September 1928, pp. 1-2, CRS A431, item 59/450.

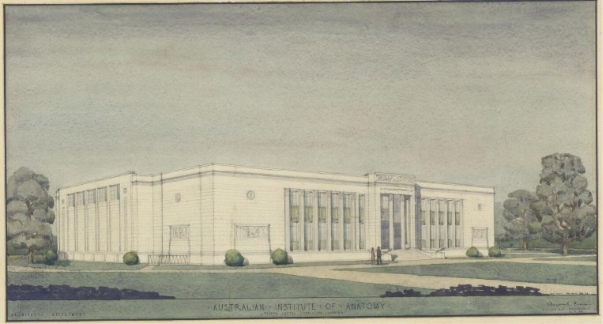

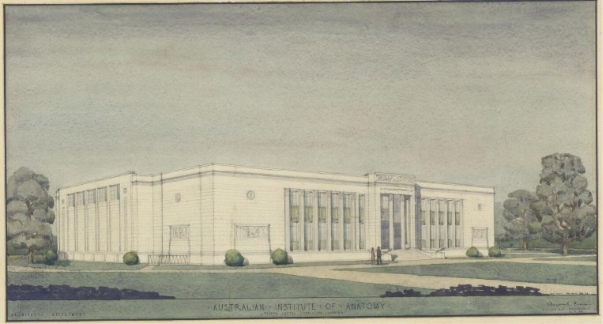

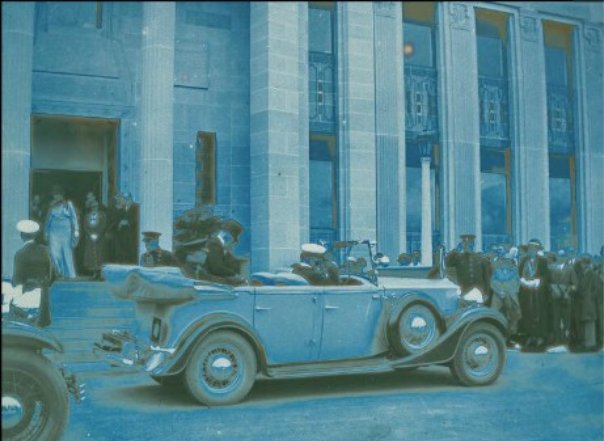

Figure 6: Australian Institute of Anatomy by W. Heyward Morris, 1929 (National Library of Australia 2018)