Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

Management Plan – Cockatoo Island

23 June 2010

The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust acknowledges the development of this Cockatoo Island Management Plan by staff at the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, and is grateful to all those organisations and individuals who have contributed. A special thankyou is given to the members of the Community Advisory Committee and Friends of Cockatoo Island for assisting with the development of the Plan and for their invaluable comments and suggestions throughout the drafting period. Thank you also to the members of the community who attended information sessions or provided comment, and to the staff of the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage, and the Arts, who made a valuable contribution to the preparation of the Plan.

Authors:

Staff of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

Main Consultant Providers:

Government Architect’s Office, NSW Department of Commerce

Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd

John Jeremy

For full list of consultants see Related Studies section of Plan

Copyright © Sydney Harbour Federation Trust 2010.

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the

Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without

written permission from the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust. Requests

and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to

the Director Communications, Sydney Harbour Federation Trust PO Box

607, Mosman, NSW 2088 or email to info@harbourtrust.gov.au

For more information about the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust or to

view this publication online, visit the website at:

http://www.harbourtrust.gov.au

Table of Contents

Introduction

Aims of this Plan

Planning Framework

Relationship with the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan

Related Trust Policies and Guidelines

Statutory Planning Context

Non Statutory Planning Strategies

Plans Prepared for Neighbouring Lands

Site Description

Site History

Analysis and Assessment

Heritage Listings

Conservation Management Plans

Archaeological Assessments

Cultural Landscape

Natural Values

Site Contamination

Remediation and Decontamination Works to Date

Compliance with the Building Code of Australia

Structural Condition of Buildings

Condition of Services

Transport Management

Noise Impact Assessment

Heritage Values

Cockatoo Island’s Character

Summary Statement of Significance, Convict Buildings and Remains CMP

Summary Statement of Significance, Cockatoo Island Dockyard CMP

National and Commonwealth Heritage Values

World Heritage Listing Nomination

Potential World Heritage Values

World Heritage Listing - draft Summary Statement of Significance

Condition of Values

Management Requirements and Goals

Conservation Policies

Outcomes

Vision

Design Outcomes

Precinct Outcomes

Accessibility

Noise

Water Sensitive Urban Design

Remediation and Management Strategy

Ecologically Sustainable Development

Interpretation

Implementation

Monitoring and Review of the Plan

Images Acknowledgements

Related Studies

Appendices

On 21st August 2003 the Minister for the Environment and Heritage approved a Comprehensive Plan for the harbour sites managed by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust (the Trust). The plan, which was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust Act 2001, sets out the Trust’s vision for the sites under its control.

A requirement of the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan is that more detailed management plans are prepared for specific precincts, places or buildings. In addition to this the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999 requires the Trust to make plans to protect and manage the National Heritage values and Commonwealth Heritage values of National and Commonwealth Heritage Places. Cockatoo Island is identified on both the National and the Commonwealth Heritage Lists.

Cockatoo Island is also one of eleven sites that will form a proposed serial nomination of Australian Convict Sites for World Heritage listing. This plan includes measures to protect the potential World Heritage values of Cockatoo Island.

Accordingly, the purpose of this Management Plan is to guide the outcomes proposed in the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan, to satisfy the requirements of Schedules 5A and 7A of the EPBC Act Regulations, 2000 and to be consistent with the National and Commonwealth Heritage management principles.

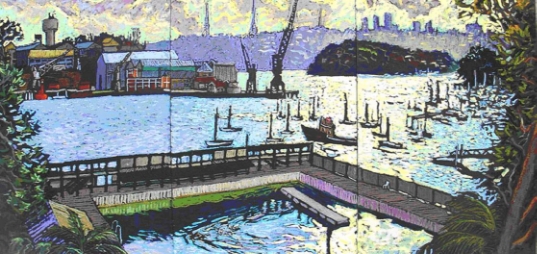

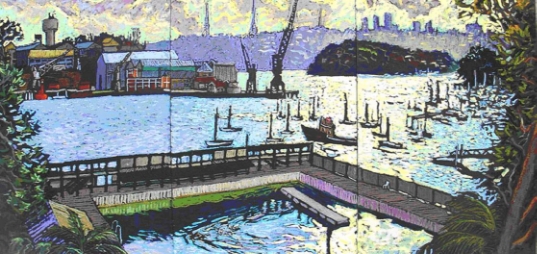

The Comprehensive Plan proposes the revival of Cockatoo Island as a working maritime site and as a functioning, active part of Sydney’s cultural life. Its heritage values are to be protected and the island is to be freely accessible to the general public. The island’s rich history will be recognised and will inspire its revival.

The island will become home to an array of complementary uses and activities, ranging from those which tap into the island’s past, such as maritime and related industries, to entirely new uses such as cultural events, short-stay accommodation and restaurants.

In keeping with tradition, existing buildings and structures will be adaptively reused. Significant heritage artefacts will be conserved and will form an important aspect of the island’s attractions as well as facilitating people’s understanding of its past. Parkland and vantage points will provide opportunities for people to enjoy the island and the harbour.

The island’s future has generated great public interest and passion. However, its planning is also recognised by many as challenging. This is due to the:

- Difficulties of transporting materials and passengers to and from it;

- Number, variety and condition of the buildings;

- Complex heritage overlays;

- Size of the island;

- Contamination; and

- Hazardous conditions (public safety).

Having regard for these complexities and the length of time during which this plan will be implemented, the Trust concluded that it is not desirable to attempt to identify detailed outcomes for the whole island. Accordingly, this plan aims to provide a long-term vision and a framework for decision making that is sufficiently flexible to accommodate new ideas and change and that is consistent with and does not adversely impact on the statutory heritage values of the place. The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust is committed to the conservation of the National and Commonwealth Heritage values of its places, and this commitment is reflected in its Act, its corporate planning documents and processes. This Management Plan, which satisfies sections 341V and 341S and of the EPBC Act 1999, provides the framework and basis for the conservation and management of Cockatoo Island in recognition of its heritage values.

The Trusts’ Heritage Strategy, which details the Trusts’ objectives and strategic approach for the conservation of heritage values, was prepared under section 341ZA of the EPBC Act 1999 and accepted by the Minister. The policies in this plan support the directions of the Heritage Strategy, and indicate the objectives for identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to all generations of the Commonwealth and National Heritage values of the place.

Commencement Date

The land covered by the Management Plan is shown by broken black edging on the plan at Figure 1. All of the land including the bed of the harbour is within Lot 1 DP 549630 and is in the ownership of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

To achieve the Trust’s vision for the island this Management Plan aims to:

- Conserve, protect and manage the National, Commonwealth, and potential World Heritage values of the island as an historic place within Sydney Harbour and facilitate its interpretation, appreciation and adaptive reuse;

- Be consistent with the National and Commonwealth Heritage management principles;

- Provide general public access to the island;

- Facilitate the transport of people and goods to and from the island by providing appropriate waterfront infrastructure;

- Revive the island by reintroducing maritime and related industry as well as a range of complementary uses including cultural, entertainment, dining, education, recreation, retail, offices and studios;

- Establish Cockatoo Island as a place of public enjoyment by providing public open space and the creation of venues for cultural events; and

- Apply the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development to the revitalisation of the island.

In doing this, it also aims to:

- Provide opportunities for visitors to understand and appreciate the rich and varied history of the island by providing for site interpretation, education and appropriate uses;

- Provide visitor facilities and amenities including safe pedestrian paths, viewing areas, lookouts and access to the convict precinct, the docks, tunnels, cranes and other historic structures;

- Realise the potential for easy access including access for the disabled;

- Enhance views to and from the island;

- Manage the flora and fauna remaining on the site and interpret the original harbour landscape;

- Improve the quality of stormwater runoff in order to reverse adverse impacts on the harbour; and

- Apply remediation strategies consistent with the range of proposed land uses while reducing any adverse environmental impact on the harbour.

This Management Plan is the middle level of a three tiered comprehensive planning system developed to guide the future of the Trust’s lands.

The other levels are:

- The Trust’s Comprehensive Plan - this is an overarching plan that provides a process for the preparation of Management Plans; and

- Specific projects or actions - actions are defined in the EPBC Act 1999 and are similar to the concept of development in NSW planning legislation.

This Management Plan has to be interpreted in conjunction with the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan, in particular the Outcomes identified in Part 5 of the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan and the Objectives and Policies in Part 3.

The Outcomes diagram in Part 5 of the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan for Cockatoo Island is reproduced at Figure 2. Conservation policies in this plan provide guidance on how these outcomes can be managed in a way that protects, conserves, presents and transmits to all generations the National and Commonwealth Heritage values.

The Objectives and Policies most relevant to this Management Plan are those relating to working harbour, tourism, contamination, water quality and catchment protection, cultural heritage, adaptive re-use of places and buildings, access, open space and recreation, and education. These Objectives and Policies were addressed during the assessment of the site and are discussed in more detail in the relevant sections of this plan.

There are a number of overarching Policies and Guidelines foreshadowed in the Trust’s Comprehensive Plan that will be developed over the lifetime of the Trust and that will also guide the conservation and adaptive reuse of the island. Current relevant policies are:

- The Trust’s Leasing of Land and Buildings Policy;

- The Trust’s policy for the Leasing of Land and Buildings to Community Users;

- The Trust Event Policy;

- The Trust’s Heritage Strategy; and

- The Trust Interpretation Strategy for Cockatoo Island

This Management Plan has regard for these existing policies. If or when other Trust Policies and Guidelines are developed this plan will be reviewed to ensure that they do not impact adversely on the National and Commonwealth heritage values.

Commonwealth Legislation

State Legislation

Sydney Regional Environmental Plan- Sydney Harbour Catchment 2005

This SREP applies to the whole of Sydney Harbour’s waterways, the foreshores and entire harbour catchment. It provides a framework for future planning, development and management of the waterway, heritage items, islands, wetland protection areas and foreshores of Sydney Harbour. Under the SREP, Cockatoo Island is included in the catchment area of Sydney Harbour, as a foreshores and waterways area and is also listed as a strategic foreshore site. The planning principles of the SREP relevant to the island include:

- Development that is visible from the waterways or foreshores is to maintain, protect and enhance the unique visual qualities of Sydney Harbour;

- Development is to protect and, if practicable, rehabilitate watercourses, wetlands, riparian corridors, remnant native vegetation and ecological connectivity within the catchment;

- The number of publicly accessible vantage points for viewing Sydney Harbour should be increased;

- Public access to and along the foreshore and waterways should be increased, maintained and improved;

- Public access along foreshore land should be provided on land used for industrial or commercial maritime purposes where such access does not interfere with the use of the land for those purposes;

- The use of foreshore land adjacent to land used for industrial or commercial maritime purposes should be compatible with those purposes;

- Water-based public transport (such as ferries) should be encouraged to link with land-based public transport (such as buses and trains) at appropriate public spaces along the waterfront;

- The provision and use of public boating facilities along the waterfront should be encouraged;

- Sydney Harbour and its islands and foreshores should be recognised and protected as places of exceptional heritage significance;

- An appreciation of the role of Sydney Harbour in the history of the Aboriginal and European settlement should be encouraged;

- Significant fabric, settings, relics and views associated with the heritage significance of heritage items should be conserved; and

- Archaeological sites and places of Aboriginal heritage significance should be conserved.

Local Government

Sharing Sydney Harbour Access Plan

In addition to its statutory plans, the State Government has prepared the Sharing Sydney Harbour Access Plan (SSHAP). This Plan identifies a network of new and improved public access ways for pedestrians and cyclists, and waterway facilities for recreational watercraft.

Cockatoo Island is identified as a site of cultural interest, which presents new opportunities for public access.

Plans and policies prepared by neighbouring land managers provide a context for this Management plan. The following are particularly relevant:

New South Wales Maritime Authority

The NSW Maritime Authority is responsible for the bed of the harbour and its tributaries, including the conservation and protection of the marine environment. The Authority is also responsible for approving (or requiring the demolition of) wharves or other structures that extend beyond the boundary of the Trust land. To assist in these processes it has prepared a number of policies that it considers when deciding whether to grant approval or not. These include:

- Obtaining permission to lodge a development application;

- Engineering Standards and Guidelines for Maritime Structures; and

- Marine Habitat Survey Guidelines.

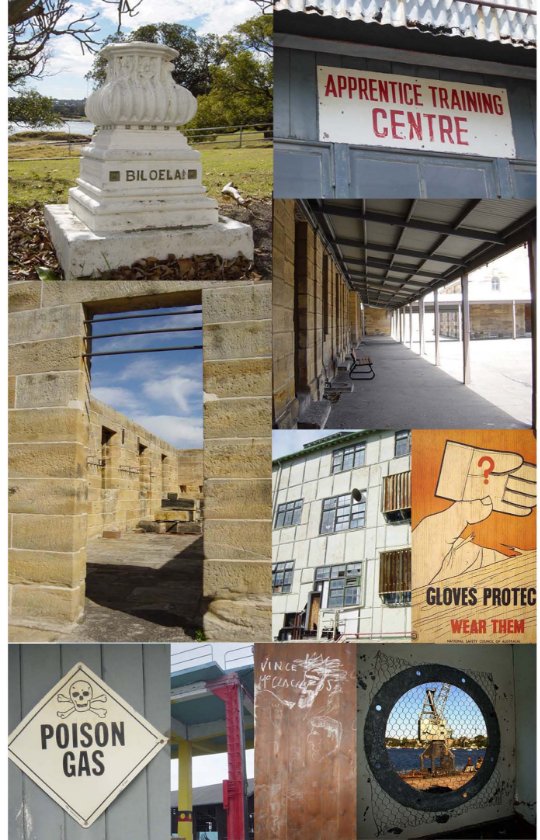

The island is characterised by a diversity derived from its incremental development over a long period of time. This diversity, combined with the topography make it difficult to perceive the island as a unified entity.

The island has been vacant since 1992 and many of the buildings have deteriorated during this time. Some areas also contain contamination and industrial hazards resulting from over a century of shipbuilding. The lower area of the island still accommodates a range of industrial buildings, concrete pads from demolished buildings, cranes, dry docks and wharf related structures. However, many buildings and wharves were demolished after the closure of the dockyard, and this has resulted in large open areas on the northern and eastern foreshores.

Figure 4 - Precinct Areas identifies the areas referred to in this management plan as the Southern, Northern and Eastern aprons and the Plateau. Appendix 1 identifies all of the locations and building numbers of existing and previous buildings and their uses.

The Plateau or upper area of the Island includes three distinct areas. At its western end there is the convict gaol and associated sandstone buildings and walls. The central area includes a row of multi-storey workshops that were built on the sites of the former convict water tanks and quarry yard. The eastern end is characterised by a group of houses whose backyards meet, forming an arrangement of lawns, garden beds, and exotic trees. Also included in this area are the convict grain silos, the WW II searchlight tower and the landmark water tower

Surrounding Lands

Cockatoo Island is the largest of the three islands that were known in the 1820s as the ‘Hen and Chickens’. The other two are Snapper which is also a Trust site, and Spectacle, which is occupied by the Australian Navy. See Figure 5- Local Area Context.

The island also has a relationship with the surrounding mainland areas, including Woolwich, Birchgrove, Balmain, Rozelle, Drummoyne and Birkenhead.

The Parramatta River foreshores of Woolwich face directly onto the Island. This includes the recreational areas of Clarkes Point Reserve and the Horse Paddock, the Hunters Hill Sailing Club and Woolwich Marina. Further up the slope the land is zoned for residential purposes and is characterised by low to medium density housing. There are also a number of restaurants and cafes and the Woolwich Pier Hotel located at the top of the ridge.

For all of these residential areas, the impacts on amenity of noise, light, traffic and parking are important. Accordingly the Trust has been careful to address these issues during the preparation of this Management Plan. See the Analysis and Assessment and the Outcomes sections of this plan.

Aboriginal Heritage

European Heritage

Arrival of the Convicts

A Dockyard and Prison

Convict labour was also used to build the fine sandstone Engineers’ and Blacksmiths’ Shop (Building 138), which still stands near the dock. This is one of the first buildings associated with the operation of the Fitzroy Dock and was built to a Royal Engineers’ design, with the Portsmouth Steam Factory in England used as the prototype. The machinery in the workshop was operated by steam until 1901 and some evidence of the original equipment remains.

Reformatory and Training

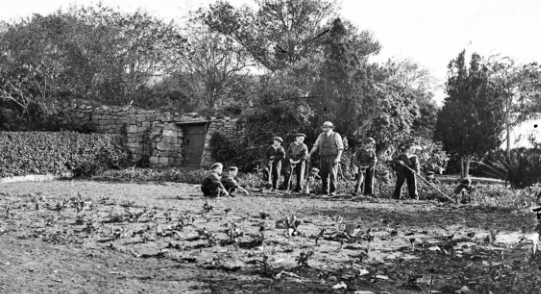

At the same time as the reformatory and industrial school were accommodated on the island, an old ship, the Vernon, was anchored off its northeast corner and was used to house delinquent and orphaned boys. In 1890 the Vernon was replaced by the Sobraon, which remained there until 1911. The Sobraon was a much larger ship and was able to accommodate 500 boys.

The boys were segregated from the girls, and, later, from the prisoners at Biloela Gaol. They were taught trades such as tailoring, carpentry, shoe and sail making and space was made available on the island for them to grow vegetables. A patch of land on the apron east of Biloela House (Building 22) was used as their recreation area (see Figure 12) and a swimming enclosure was later added. However, subsequent development on the island has removed all visible evidence of their existence.

A Gaol Again

Dockyard and Shipbuilding

Figure 15: HMS Galatea in the Fitzroy Dock, 1870. The Galatea was visiting Australia as part of an around the world tour undertaken by Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. The elegant stone building to the right of the dock is the Engineers’ and Blacksmiths’ Shop (Building 138), which was Figure 15: HMS Galatea in the Fitzroy Dock, 1870. The Galatea was visiting Australia as part of an around the world tour undertaken by Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. The elegant stone building to the right of the dock is the Engineers’ and Blacksmiths’ Shop (Building 138), which was

built by convict labour in various stages. This photograph shows the first two stages including the bell tower. The building was subsequently altered in the early 20th century by the addition of a second floor to accommodate the brass finishing shop and is now obscured by new buildings that have been erected in front of it. |

Commonwealth Naval Dockyard 1913-1933

Wartime

Privatisation

World War II

Peacetime

The Last Ships

Closure

In 2004 the Government Architect’s Office (GAO) of the NSW Department of Commerce were engaged to prepare a Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for Convict Buildings and Remains.

In the same year Godden Mackay Logan (GML) was engaged to prepare a CMP for the dockyard and industrial aspects of the island’s history. Its scope included the whole island as it relates to the history of the dockyard and related uses.

Also commissioned were CMPs for the following individual buildings:

- Building 58 (Powerhouse) - Godden Mackay Logan 2005

- Buildings 6, 12 and 13 - Conybeare Morrison Pty Ltd 2004

- Buildings 10, 21, 23, and 24 - Robertson and Hindmarsh 2003

The methodology used in the CMPs to assess significance generally follows the format set out in James Semple Kerr’s The Conservation Plan. The CMPs assessed the cultural significance of the island by examining the way in which its extant fabric demonstrates its function, associations and aesthetic qualities.

The National and Commonwealth Heritage values included in this plan were taken from the statutory listings. However, summary statements of significance from the CMPs have also been included and these assist in describing the National and Commonwealth Heritage values of Cockatoo Island.

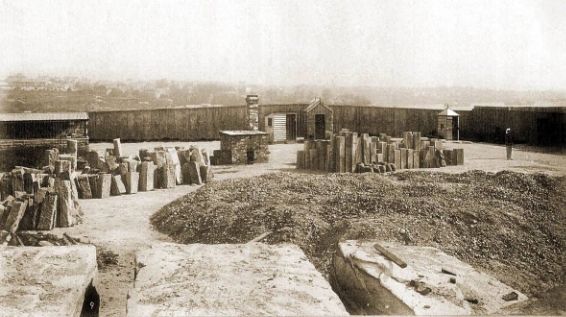

The assessment found that evidence of many additional buildings and features from the convict and institutional era are likely to be present as an archaeological resource below the current ground level. The natural rock of the island is often very close to the surface, thus evidence of features that have been cut down into the rock, like trenches, wells and pits, are likely to survive.

The draft GML CMP also included an archaeological assessment which summarises the potential and known key dockyard and industrial archaeological resources on Cockatoo Island and identifies their archaeological and heritage significance. The report determined that subsurface archaeological features and deposits relating to the dockyard and industrial uses may be present throughout Cockatoo Island, although most of the island has been subject to disturbance.

Both consultants combined to produce the ‘Cockatoo Island Archaeological Management Principles’ in May 2007 as a guideline for all future work on the Island.

In those areas identified as having archaeological potential, a monitoring program will be carried out during any sub surface exposure or removal of superficial layers. A qualified archaeologist will undertake this monitoring.

The draft GML and GAO CMPs describe Cockatoo Island’s cultural landscape as follows:

The cultural landscape of Cockatoo Island is a continuing landscape, and many of the earlier convict-built components of the site have vanished to make way for additional dockyard facilities. The industrial character of the cultural landscape of the island has developed from the interaction of maritime and prison activity and is articulated by man made cliffs, stone walls and steps, docks, cranes, slipways and built forms. The changing pattern of use of the island was to facilitate industrial production, as technology changed and as demand increased. The cessation of shipbuilding activities on the island and the clearing of buildings that occurred resulted in substantial evidence of the cultural landscape being removed, particularly to the aprons. Most of the significant vegetation on the island comprises planted ornamentals on the central sandstone area, although there are also elements such as the banks of ferns growing on the sandstone cutting beside the Turbine Hall.

The draft CMPs recommend that the cultural landscape be conserved by:

- retaining remnant natural topography, indigenous vegetation and fauna;

- retaining remnant evidence of gardens and significant tree plantings, which demonstrate different cultural expectations and aspirations in different periods and social contexts;

- Limiting vehicles on the island; and

- Retaining major land form modifications, including reclaimed foreshore areas, cuttings, walls, excavated docks, tunnels and roadways which express significant developments and events on the island.

In 2003 GIS Environmental Consultants were engaged to undertake a flora and fauna study of Cockatoo Island. See Figure 24-Environmental Considerations.

The study found that the:

- Original flora and fauna on Cockatoo Island would have been an unusual mixture of species due to an absence of fire, isolation caused by the surrounding seawater, the lack of reliable source of fresh water and the strong marine influence;

- Island would never have had a high diversity of species;

- Island is highly developed and does not provide much quality habitat for native fauna;

- Grassed areas on the lower levels provide foraging habitat for lapwing plovers, herons and starlings, but there is little cover for bush birds;

- Hard covered surfaces on the south and west sides of the island provide basking areas for skinks;

- Grey-headed Flying foxes, listed as a Vulnerable Species, forage on Port Jackson Figs on the northern slope. These figs are also a potential food source for the Superb Fruit-Dove;

- Vacant buildings provide shelter for birds, skinks and rats;

- Vegetative layers support a range of invertebrate prey suitable for insectivorous birds, mammals, and reptiles;

- Island is considered to be ideal habitat for several species of insectivorous microbats, many of which are identified as threatened species under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act, 1999. However, no microbats were detected;

- Pilings and piers extending from the south side of the island provide roosting habitat for seabirds such as Pied Cormorant, Little Pied Cormorant and Little Black Cormorant; and

- Rocky foreshore provides potential habitat for Water rats and a wide variety of marine animals and plants. In particular, the foreshore on the northern side of the island provides habitat for a colony of Silver Gulls.

The report also identified:

- Two tree species listed as Vulnerable in the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act 1999. These are the Narrow-leaved Black Peppermint (Eucalyptus nicholii) and the Magenta Lilly Pilly (Syzygium paniculatum). Both of these trees were planted as ornamental specimens; and

- Two uncommon species of fern allies, the Scrambling Club moss (Lycopodium cernuum) and the Skeleton Fork Fern (Psilotum nudum). The Skeleton Fork Fern appears in small patches along the cliff face between the Parramatta Wharf and the Turbine Work Shop (Building 150) and the Scrambling Club moss occurs near the entrance to Tunnel No 3.

The report recommended that:

- The large Port Jackson figs should be protected to provide foraging habitat for the vulnerable Grey-headed Flying Fox and the Superb Fruit-Dove;

- The Narrow-leaved Peppermint and the Magenta Lilly Pilly should be protected;

- The fern allies should be protected by ensuring spraying or clearing of plants on the cliff edge does not occur;

- The fern allies be identified with appropriate interpretive signage;

- Bush regeneration should be carried out on the weedy areas on the sides and top of the plateau;

- The maintenance of gardens should ensure that exotic species are not allowed to invade the regenerated areas;

- A vegetation management plan may be appropriate to ensure suitable species are planted in the correct locations, to ensure weeds are controlled and bushland areas will becomes self sustaining;

- Fire should not be used as a bush regeneration technique;

- A nesting area at the western corner of the Northern apron should be dedicated for a limited population of Silver Gulls to ensure the viability of the Silver Gull colony; and

- Insect killing lights (bug zappers) should not be used on the island so that a food supply for bat species is maintained.

Cockatoo Island is one of many sites in Sydney Harbour that serves as a nesting point for Silver Gulls. The population of gulls on the island are aggressive and in some areas their excrement – which is acidic- is causing damage to the building fabric. The Trust will investigate ways of controlling the population of gulls and will liaise with other relevant stakeholders in relation to this.

Understanding the history of ship building and engineering on Cockatoo Island provides a key to understanding the environmental condition of the island. Contamination on the island has resulted from the previous land filling and waste disposal practices as well as the spillage and release of chemicals and materials. Consequently, various types of contaminants have been reported in soils, surface-water, groundwater and near shore sediments. Hazardous materials are also associated with the various buildings and structures, some pavements and other building surfaces.

Extensive assessment of contamination was carried out from 1991 to 1998. The Cockatoo Island Environmental Characterisation report, prepared by the Cockatoo Island Rehabilitation Consortium (CIRC) provides a useful review of contamination on the island at that time. Since assuming ownership of the island, the Trust has commissioned Sinclair Knight Merz to conduct an independent environmental audit, and prepare a draft Site Audit Report (SAR). A remediation and environmental management strategy has also been developed based on the previous assessment reports, and the recommendations provided by the audit. The remediation strategy and other environmental requirements are to be documented in the Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for the island. A summary of this strategy is provided in the ‘Outcomes’ section of this plan. The Trust has also undertaken some building decontamination, remediation, assessment and monitoring projects, as discussed later in this section.

The following summary of site contamination is based on the previous reports:

Soils and fill

In its original state, Cockatoo Island was a heavily timbered knoll occupying approximately 13 hectares. Filling occurred from the early development of the site, increasing the island’s area to the current 17.9 hectares. From the establishment of the penal settlement, cut fill and trade wastes were disposed by addition to the Island’s foreshores. After the Fitzroy Dock was completed in 1857, the industrial component of the fill is likely to have increased. From 1910 industrial trade wastes were transported out to sea for disposal, however the disposal of building rubble and other solid wastes continued along the shorelines. By 1917, all but the north-western shoreline was completed to the present extent.

Barge disposal at sea ceased in 1940 and trade wastes were added to the rubble used for shoreline advancement up to 1960. Shoreline development was taking place only in the northwest part of the Island at that time. As a result, the fill in this area is very mixed, including sandstone, demolition rubble, slag, ash, coke, scrap metal, fibro cement and general rubbish. Contamination in these materials is predominantly heavy metals, Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and asbestos. Historical evidence also suggests that process wastes were routinely disposed in this area. These wastes have included electroplating sludge (heavy metals, cyanides) and anti-foul wastes (mainly Tributyltin - TBT).

Studies have shown that fill in other areas of the island have a higher component of natural materials, being mainly sandstone, marine sands and silt with some building rubble and process wastes. However, in addition to filling, there were other sources of contamination (or laydown mechanisms) at Cockatoo Island. The Sinclair Knight Merz draft report has listed the main types:

- Localised dumping and / or spillage of wastes associated with former operations, examples include:

- The former pipe laundry (Buildings 32 and 33) area, located at the north eastern corner of the site where chlorinated solvents were used and stored;

- Grit blast wastes containing heavy metals that remain on the surface of the southern apron and in the power house/ coal bunker area;

- Leakage of chemicals or fuels from above and below ground storage tanks, pits and associated pipe work;

- Atmospheric fallout from operations that may have impacted the exposed near-surface soils across the site, such as from the boiler house chimney, incinerator, furnace stacks etc. Atmospheric fallout is likely to have been responsible for contamination of the grassed areas of the plateau, where there were no recorded industrial operations;

- Leakage, outflows and accumulation of contaminated sediments and wastes in the sewerage and stormwater systems, including disused septic tanks;

- Discharge to soils from hazardous building materials, including lead based paints, asbestos sheeting and lagging, PCB electrical fittings and coal tar based bitumen pavements;

- Pesticide/ herbicide treatments for control of rodents and weeds;

- Contamination associated with special processes, such as the X-Ray laboratory, weapons stores etc, and;

- Migration of contaminants into the Docks and sediments in surrounding waterways.

The main contaminants of concern in soils and fill are considered to be metals and metalloids, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, organotin compounds and asbestos. However, other contaminants such as petroleum hydrocarbons, cyanides, solvent chemicals or polychlorinated bi-phenyl compounds may occur in localised areas.

In 2004 the Trust commissioned HLA Envirosciences to conduct the following soil assessments to address information deficiencies identified by the auditor:

- Supplementary soil assessment of the plateau area, and

- An asbestos in soils survey covering the island

The supplementary assessment of the plateau area was carried out so that remediation requirements could be defined for this area, particularly with respect to PAHs and depth of contamination. This assessment confirmed that metals (mainly lead) and PAHs exceed the relevant health-based criteria for the proposed uses of the site.

The asbestos in soils survey was carried out to map the distribution of asbestos based materials within surface soils, which had not been adequately addressed in previous assessments. Asbestos materials were observed and detected in various areas, mainly on the northern apron, southern apron and plateau. All visible bonded asbestos fragments identified by this assessment were removed by hand in February 2005, although some individual fibres remain. Remaining asbestos fibres are not considered to present a significant risk to users of the site as long as the soils in these areas are stable and remain undisturbed. This has been achieved in the short term in the plateau area by laying down temporary clean surface cover in priority areas consisting of topsoil/ grass or gravel. Long-term requirements will need to be considered in the remediation of each area.

There is sufficient data to indicate that soils in all areas of Cockatoo Island contain contamination exceeding one or more of the health-based criteria applicable for the land uses being considered by the Trust.

Stormwater and Sewerage System

Contaminated wastes from site operations were either disposed or washed into the stormwater and sewerage systems over the years. Much of these systems are in poor condition, with sludge and grit remaining in pits, lines and tanks. Assessment of wastes in these systems has shown elevated levels of heavy metals and PAHs, however other contaminants may also be present. This represents a potential source of ground contamination, which may become mobile under high flow conditions and migrate into the surrounding aquatic environment.

Currently, stormwater either flows directly to the harbour, or via the remaining system of pits and pipes. Some ponding and ground infiltration also occurs, particularly in areas where buildings have been demolished and ground slabs remain. The island’s sewerage system, which is no longer in use, was comprised of:

- Sewerage treatment plant (Building 56), located on the western side of the island adjacent to the Power House and Pumping Station;

- A sewerage transfer station (Building 149), and

- At least 9 septic tanks located around the site

The Trust has installed a small temporary sewerage treatment plant to meet the needs of visitors and the workforce engaged for rehabilitation of the island.

Surface and Groundwater

A number of surface water and groundwater investigations were undertaken on Cockatoo Island in the 1990s. In 2001, the Trust also carried out a program of water quality monitoring in harbour waters surrounding the island (PPK, 2001). In summary:

- Dissolved copper, zinc, mercury and organotin compounds are considered to be the main contaminants of concern in groundwater, as they have been recorded as elevated with respect to the Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality, 2000 (ANZECC). Groundwater quality has been noted to vary significantly within fill material over short distances;

- Surface water investigations carried out in 2001 identified that copper, zinc and tributyltin were the main contaminants of concern for surface waters surrounding the site. However, only zinc may be having a marginal impact on harbour water quality as copper and tributyltin were not elevated with respect to background water quality, and;

- Hydrocarbons, including volatile chlorinated compounds have been identified in groundwater (and soils) in the region of the former pipe laundry.

In 2004, the Trust commissioned the following studies, based on the auditor’s recommendations:

- Soil vapour and groundwater assessment in the Pipe Laundry area; and

- Ground and surface water monitoring program.

The Pipe Laundry assessment was carried out to determine the current extent of hydrocarbon contamination in the area. While hydrocarbon contamination had been identified in groundwater and soil vapour in this area in the past, this assessment identified that this was now not the case, and that concentrations appear to have naturally attenuated. Importantly, hydrocarbon was also not found in groundwater down gradient of the Pipe Laundry area.

Initial results (December 2004) of the ground and surface water monitoring program confirmed the previous results, with the following exceptions:

- Cadmium was recorded in ground water exceeding the relevant trigger level in the northern part of the site;

- Elevated concentrations of organotin compounds exceeding the relevant trigger levels were detected in all eight surface water locations around the site; and

- No heavy metals, PCBs or free cyanide concentrations were detected in any surface water samples.

As these waters are not currently utilised for drinking or recreation, there is limited opportunity for exposure to this contamination. However, there is potential for impact on the local harbour environment, particularly as background levels within the harbour decrease due to the removal of other sources of this contamination in the harbour. The Trust will continue ground and surface water monitoring on an initial quarterly basis, as remediation and management of the island progresses.

Near Shore Sediments

Previous assessment has shown that sub-surface sediments surrounding Cockatoo island and in the Sutherland and Fitzroy docks are contaminated with respect to the ‘Interim’ Sediment Quality Guidelines from ANZECC (2000), which the NSW Department of Environment and Conversation (DEC) has endorsed. The principal contaminants exceeding these guidelines are copper, lead, mercury, zinc and tributyltin.

CIRC (1998) carried out a review of sediment quality data immediately surrounding the island, as well as in the surrounding region of the harbour. The CIRC concluded that while elevated concentrations of contaminants were present both within the island’s boundary and nearby, contaminants in sediments remote from the island were also at elevated concentrations, and that any further investigations would need to consider the sediment data in the context of the surrounding environment.

Potential human health risks from sediment contamination may arise from the consumption of fish, or by direct contact during swimming or wading. CIRC (1998) considered that this risk was low, based on available fish tissue analytical data and the low potential for contact with sediments. CIRC (1998) did not recommend any specific remediation or management requirements for the sediments. This was largely due to the absence of a regulatory framework at that time.

The Site Auditor (SKM, 2003) also reviewed the sediment data around Cockatoo Island, and considered that:

- There was an adequate level of chemical information for most contaminants of concern in sediments, both surrounding the island and in the docks, with the exception of Tributyltin;

- This information indicated that concentrations of copper, lead, mercury, zinc and tributyltin in sediments within the docks and around the island exceeded the relevant criteria from ANZECC (2000) and background concentrations;

- Available information indicated that sediment contamination is also present in large areas of the waterways surrounding the island, and;

- It was not yet possible to assess the risks to human health and the environment from contaminated sediments around Cockatoo Island, and that further action would be required before an appropriate management and or remediation strategy could be defined.

The auditor recommended that additional information be gathered to assess the bioavailability of contaminated sediments in accordance with ANZECC 2000. The Trust’s response to these recommendations, as well as an interim sediment management strategy is discussed in the Outcomes section of this plan.

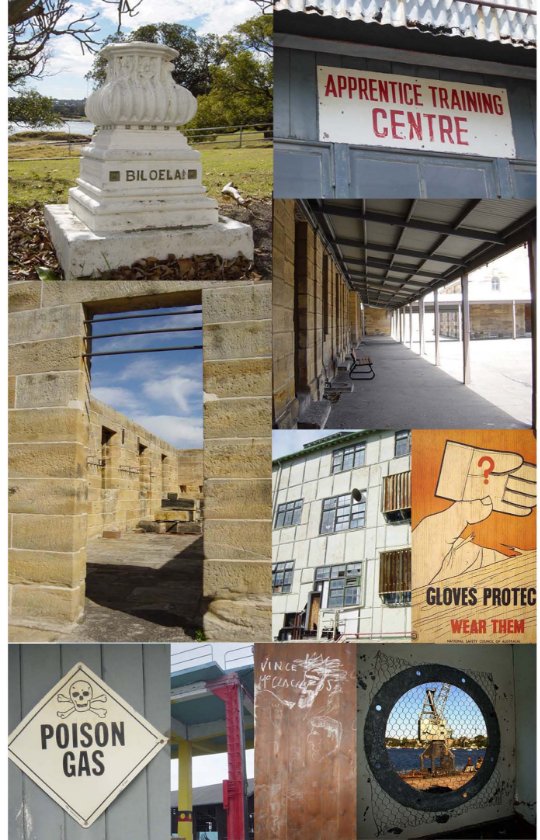

Hazardous Materials

Residual hazardous materials associated with buildings and structures may present health hazards for future use of the site, and may be a source of soil and surface contamination in all areas. These materials mainly include asbestos and asbestos containing materials, Synthetic Mineral Fibre (SMF), deteriorating lead paint systems, poly-chlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dusts and sediments on building surfaces containing lead and other inorganic and organic contaminants.

In October 1998 Woodward-Clyde and CMPS&F undertook an environmental characterisation study of Cockatoo Island for the Department of Defence. As part of this study, a hazardous materials survey of materials associated with buildings, structures and machinery was conducted. The Trust has also conducted further detailed surveys of buildings in order to prepare hazardous materials abatement plans for implementation prior to building refurbishment, demolition or lease. In summary:

- Small amounts of friable asbestos materials remained on the site at the start of the Trust’s occupation. These include asbestos insulation on small furnaces, boilers and pipes, asbestos seals and gaskets, asbestos cored fire doors and globe supports. Most of these materials have or are being removed. The majority of the remaining asbestos materials are in the form of asbestos cement products, such as corrugated asbestos cement (AC), and flat AC sheet walls and ceilings. Other minor materials include asbestos backing boards and arc shields in electrical cabinets and AC fragments in some locations. Materials have been found to be in generally good to fair condition, and do not provide an unacceptable immediate health risk while they are undisturbed.

- SMF exists in several buildings in the form of roof insulation batts and insulation around hot water pipes. These materials are generally in good condition, and do not pose a health risk while they are undisturbed.

- More than 50% of the sample capacitors associated with light fittings contained elevated levels of PCBs, which will require management as Scheduled PCB wastes. Electrical transformers remaining on the island may also contain PCB contaminated oil.

- Paint samples collected from building surfaces have shown generally all paint systems on the island may be considered to contain lead, ranging up to 26% w/w, plus other heavy metals. The majority of the lead-based paint systems identified show signs of deterioration and in many areas, paint systems were blistering and peeling. During any refurbishment of buildings, paint debris should be handled and disposed of according to applicable standards and guidelines. Demolition of buildings does not require removal of paints from surfaces.

- Samples collected from the interior of buildings reported elevated lead concentrations, which may be attributable to deteriorating paint surfaces. Dust samples collected from the Powerhouse contain elevated concentrations of mercury, which are likely to be due to past spillages. Accessible dusts are to be removed from within the buildings to be retained prior to permitting public access.

- Other miscellaneous hazardous materials include small volume chemicals, oily and aqueous liquid wastes in tanks and pits, electrical wastes (batteries, transformers and switch boards), metal swarf and general rubbish.

It is the Trust’s policy to undertake hazardous materials survey, removal and abatement programs prior to building refurbishment or demolition. To date this has been carried out for southern apron buildings, eastern apron buildings (including the turbine and machine halls buildings) as well as the plateau workshops and convict precinct. Any remaining hazardous materials in these areas, such as AC sheeting in good condition, is to be managed in accordance with hazardous materials register and management plan prepared for the site.

It is understood that the metal trades and fabrication shops on the northern apron were demolished in 1978. The remaining trades’ shops were demolished some time later, but before 1992. Buildings on the northern apron, including the plate shop, offices and amenities were also demolished in this period. Most of the machinery, equipment and wastes associated with the Co-Dock operation were removed with the decommissioning of the island. However some significant machinery remains. Most significant of these are the 38 cranes (11 external) from various periods of the island’s development.

In 1999/ 2000 Thiess Environmental Services carried out the following works for the Department of Defence, under the direction of the CIRC:

- Decontamination of Building 117 in ground pit associated with the electroplating facility;

- Demolition of Building 117 - electrical assembly building in December 1998;

- Demolition of Building 121 – Laggers Shop in January 1999;

- Demolition of Building 89 – Camber Wharf muster station

- Removal and disposal of eight known underground storage tanks;

- Demolition of Wharf crane C301;

- Demolition and removal of the Old Plate Wharf, Cruiser Wharf, Destroyer Wharf, Ruby Wharf and steps and the Camber Wharf. Timber from this activity was piled in the Turbine Hall (Building 150); and

- Sea wall reconstruction in selected areas.

Concrete material stockpiles on the northern apron were recycled from clean building demolition materials generated during this period.

In 2002, the Harbour Trust carried out rehabilitation of the eastern apron and entry plaza areas, incorporating the area between the Parramatta Wharf and Buildings 137/124, to allow for public open space and short term events uses. This work included:

- Installation of new electricity and services infrastructure;

- Minor demolition of concrete footings, bolts etc. to provide an even surface in existing hardstand areas;

- Management of excavated clean and contaminated materials;

- Installation of new concrete of bitumen hardstand in localised areas;

- Placement of a clean separation layer over modified unsealed areas. This has generally comprised of a geofabric marker under clean crushed concrete, topsoil and turf;

- Preparation of an environmental completion report for this work;

- Survey, removal or abatement of hazardous materials to allow for building conservation and repairs on the southern and eastern aprons; and

- Decontamination of the stores tunnel to allow for public access.

In 2004, the Trust completed the decontamination of the Turbine and Machine Shops, and carried out a project for recycling and disposal (where appropriate) of mixed wastes on the northern apron.

In 2005, as part of preparations for the Cockatoo Island Festival, the Trust carried out:

- Decontamination of the plateau area workshops and convict buildings;

- Removal and disposal of visible asbestos fragments and other gross wastes across all surfaces;

- Non-sealed areas of the plateau were stabilised with clean topsoil and grass or rolled VENM (Virgin Excavated Natural Material) gravels, considered protective for short-term visitation;

- Surfacing of part of the northern apron with clean materials as a commencement to capping of these areas; and

- Further recycling and removal of wastes from around the island.

Many aspects of the buildings on Cockatoo Island have a range of features that do not comply with the current Building Code of Australia (BCA). Principal among these are stairs, handrails and balustrades but there are also issues of access and mobility for people with disabilities. The existing buildings and structures on the site are to be upgraded or refurbished, to enable occupation.

Preliminary BCA assessments have been undertaken to facilitate public access for specific events such as the Cockatoo Island Festival. The key aims of these assessments were to:

- Identify potential risks for example occupational health and safety, structural, fire;

- Assess the relevant buildings in relation to the Building Code of Australia;

- Ensure that any recommendations do not compromise the heritage and aesthetic values of the island; and

- Minimise the need for the removal or adaptation of the existing fabric.

Identification of more specific building compliance issues will be carried out once individual building uses have been determined. The heritage values of the site will need to be recognised throughout the assessment process and will be an important consideration in the development of appropriate solutions.

The buildings on the island have been disused since 1992 and there had been no repairs or maintenance carried out until the Trust began undertaking repair and stabilisation works in 2001. Work undertaken by the Trust includes:

- Repairs to the Parramatta Wharf to allow safe ferry and assisted disabled access;

- Renovation to the Administration building (Building 30) to accommodate a temporary educational facility;

- Provision of toilets and essential services;

- General building repairs including painting, decontamination, waterproofing; and

- Grounds maintenance and garden restoration.

Notwithstanding this there is still a considerable amount of basic repair and maintenance necessary. The current condition of the wharves, sea-walls and related structures is similar to the condition of the buildings on the island. The majority have been disused since 1992, with little or no maintenance being carried out until the Trust began undertaking repair and stabilisation works in 2001.

In 2002, the Trust commissioned PPK Consulting to undertake a detailed survey in order to establish the extent and condition of site services. The study looked at electricity, telephone, water, fire, sewerage and stormwater services and made a number of recommendations to rationalise and upgrade the services. The study concluded that most of the services require significant repair and upgrading.

Stormwater

Currently all stormwater from Cockatoo Island discharges directly into the harbour and floor drainage from many of the buildings has historically drained into the stormwater system. Surface run-off from other potentially contaminated areas also enters the stormwater system.

It has been recommended that the existing drains should be either sealed off or cleaned of contaminated sediments to prevent future discharge into the harbour. Where future activities such as boat building will produce industrial wastewater, the surface water will need to be separated from other areas using bunds, and run-off from these areas will need to be treated separately in order to comply with NSW environmental requirements.

Sewerage

Since the Dockyard ceased operations in 1992, the island's self-contained sewerage system has been unused. The Trust has installed a temporary sewerage treatment plant for the short term, however, this will need to be improved as the occupation of the Island increases.

Sewage treatment should be consistent with the Trust's ESD objectives and could involve the recommissioning & upgrading of the existing treatment plant, the provision of a new eco-friendly system or the connection of the island to a nearby Sydney Water sewer main. Investigations to determine the appropriate treatment strategy will be undertaken.

Relining of most the existing main sewer lines commenced in early 2007. By utilising current relining technologies it has been possible to renew most main sewer lines without the intrusive impact of total pipe renewal. This has been particularly relevant in areas of high heritage value. The Trust anticipates completing the balance of sewer line rehabilitation in 2008.

Water Supply and Fire Services

The island is connected to the mains pressure supply direct from the mainland and although the water reticulation system is in reasonably good condition the pipes may need relining and progressive replacement.

Testing of the fire services infrastructure has indicated that the original sprinkler system is in reasonable condition, however repairs and maintenance will be required for the service to meet current BCA requirements. Provision of suitable fire services will be dependant on the future use of the buildings and spaces on the island, and may involve repair, augmentation or replacement of the existing system.

Mechanical, Power and Telecommunications Services

There are no significant operational mechanical services infrastructure remaining on the island such as ventilation, hoisting equipment or the like.

At the time of the island’s closure internal and external lighting was generally inoperable except for some general area lighting and the lighting of the island’s perimeter. However, the electricity system has recently been reinstated with the installation of a new AC power ring main.

The current telecommunications system to the island includes only 200 copper lines, allowing a low quality data transfer. The possibility of improving this system will be investigated.

The provision of new services and distribution will be tailored to future requirements.

In 2003 the Trust commissioned Kellogg Brown and Root Pty Ltd to prepare a Transport Management Plan (TMP) for Cockatoo Island. The aim of the TMP is to manage the demand for travel to and from Cockatoo Island through the:

- Identification of optimum land bases for the transfer of goods and people to the Island;

- Identification of required Island-based transport/transfer facilities; and

- Recommendation of a package of transport and land use management measures, designed to manage water access effectively and minimise the impacts of land bases for their surrounding areas.

Suitable Land Bases

The report identifies a number of potential land bases suitable for transfer of goods and services to the island during the island’s construction and operation periods. See Figure 25 - Land Bases. It identifies bases for everyday use and bases that would only be used occasionally. The every day land bases were selected on the basis that they could include Roll-On/Roll-Off ramp facilities, secure storage, including refrigerated storage, vehicle turning space and a limited amount of parking space. The occasional use sites have been selected primarily for their close proximity to Cockatoo Island and either have a currently available ramp or easy future access. Although the Trust site at Woolwich has been used occasionally for this purpose, the ongoing use of this site for access should remain ‘occasional’ and other land bases need to be identified.

The most suitable land bases identified are:

Everyday use (Roll-On/Roll-Off Access) -

- Common User Berth, White Bay;

- The Crescent, Rozelle Bay;

- Glebe Island Bridge West Rozelle; and

- Millers Point.

Occasional use (including construction access) -

- Horse Paddock, Woolwich;

- Woolwich Dock;

- Drummoyne Sailing Club;

- Drummoyne Boat Ramp; and

- Birkenhead Point.

Passengers

The report recommends that visitor access to the island could be by either passenger ferry or private boat. There are a large number of existing passenger ferry services that could be diverted to stop at the island as demand for travel increases. See Figure 24. The report found that during a typical weekday there are 134 ferry services that pass the island in either direction and that these services provide a total capacity of approximately 25,000 passenger ferry seats each day during the week. Although census data reveals that ferry demand is growing, there is currently spare capacity for extra passengers traveling in the counter-peak direction at off-peak times.

Key locations for visitor access by passenger ferry have been identified as:

- Circular Quay;

- Darling Harbour;

- Gladesville Ferry Wharf.

Both Circular Quay and Darling Harbour are popular tourist destinations and are served well by connecting public transport. Birkenhead Point and Gladesville Wharves were also recommended as they are both well served by ferries that currently pass close to Cockatoo Island, are served well by other public transport services and are relatively close to the Island.

On-Island Facilities

The report recommends that for operational purposes the island provide two passenger wharves and two Roll on/Roll off ramps for receiving goods and visitors. The report identifies infrastructure suitable for upgrade or redevelopment to provide access to Cockatoo Island for freight and passengers. These are:

Roll-On/Roll-Off Ramp:

- Adjacent to former Fitzroy Wharf (Southern Apron); and

- No. 2 Slipway (Northern Apron).

- Parramatta Wharf (Eastern Apron); and

- Reinstated Camber Wharf (Southern Apron).

Since this report was prepared passenger access the Bolt Shop Wharf (located on the eastern side of the island) has been upgraded and is also capable of accommodating large ferries such as the Manly Ferries.

The report also suggests that the Sutherland Wharf is suitable for craning materials on and off the island from barges or ferries.

The recommendations of this report have been incorporated into the Outcomes section of this report.

The island’s function has been highly varied, ranging from incarceration, heavy shipbuilding and engineering; to small boat construction and design, fine joinery and cabinet making. This diversity of activity is reflected both in the buildings - their materials, scale and pattern of windows - as well as the spaces created between them and their articulation by industrial infrastructure such as rails, slipways, docks, wharves and cranes. It is a place of cuttings: the hillsides cut to form cliffs and broad aprons, two docks nose to nose, rail tracks, tunnels, slipways and the grain silos cut by hand into the top of the sandstone plateau.

The island’s evolution has been accretive as it has been modified and adapted as required - to fulfil a particularly large contract, or to accommodate changes in ship size and building technology. An important character of the island derives from this reworking of existing buildings and facilities.

The island was ‘off-limits’ as a gaol and as a naval dockyard, contributing to its sense of mystique. It was also a place of innovation and learning through apprenticeship training.

- The quality of isolation inherent in the island. This was one of the main reasons for its selection as a convict prison and one appreciated by today’s visitors;

- The layering of uses and history;

- The hard-edged industrial character;

- The bleakness of the stone convict compound and associated buildings;

- The values and examples of innovation and ‘making do’ evident in many of the dockyard buildings; and

- The tradition of adaptation associated with the dockyard.

The following statements of significance have been taken from the draft Conservation Management Plans prepared for the island by Godden Mackay Logan (Dockyard CMP) and the Government Architect’s Office (Convict Buildings and Remains CMP).

The following summary statement of significance is taken from Government Architects Office, Conservation Management Plan, 2005.

Cockatoo Island is the only surviving Imperial convict public works establishment that retains most of the major buildings and works from its early construction campaigns. In combination, the physical and documentary record provides a rare opportunity to understand the system of life and work in a place of secondary convict incarceration. It appears to be the only place in the convict system that was established specifically for the purpose of hard labour. It was also unusual in its establishment close to a major centre of population.

The use of the Island for the construction and repair of maritime vessels has remained an important aspect of its use throughout its history. Substantial evidence of this use during the convict period exists in Fitzroy Dock and the associated workshop buildings. Fitzroy Dock was the first dry dock planned in Australia, constructed using advanced engineering technology and techniques. The development of the dock reflects rapidly changing applications of steam technology to shipping and ship repair and the rapid spread of information, ideas and technology among the network of professional engineers throughout the British Colonies.

Other buildings on the site, particularly the mid nineteenth century Steam Workshop complex and Biloela House, exhibit high quality stone construction, detailing and features.

Cockatoo Island has a range of archaeological resources, including rare evidence that has the potential to yield information not available from other sources, about life and work within a place of secondary punishment. They represent elements of the system of life and work on the Island not represented in extant buildings and ruins. The archaeological resources of Cockatoo Island therefore have the potential to substantially contribute to understanding of this period of Australia’s history. They also have the potential to provide a tangible experience for visitors to the Island and a direct link to the people who lived there. Later evidence relating to institutional use of the Island for the care and reform of children, contributes to the ongoing story of Cockatoo Island as a place of work and incarceration.

The development and history of Cockatoo Island is intrinsically linked to several Governors of NSW, and noted engineers and military figures, including Governors Gipps and FitzRoy, Major George Barney of the Royal Engineers, Gother Kerr Mann, and Sir William Denison.

The Island was closely associated with the Nautical Training Ships Sobraon and Vernon and is likely to contain the only surviving physical evidence of this highly successful scheme. Its use as a girls’ industrial school and reformatory also reflects a lack of adequate financial support for purpose built accommodation for juvenile care for girls in the later nineteenth century. These later uses contribute to the significance of the place but are not in themselves of outstanding heritage significance, particularly as physical remains from this period are minimal.

Cockatoo Island is a cultural landscape of State and National Significance by virtue of its location, manipulated landform, collection of buildings, works and potential archaeological resources from a significant period of Australia’s history. Cockatoo Island has outstanding heritage value to the Nation due to its early use as an imperial convict public works establishment, its ongoing use for construction and repair and the extensive evidence of these important uses that remain on the island.

Cockatoo Island’s previous dockyard, industrial, maritime and Defence uses, and the surviving physical evidence of those previous uses, are of Commonwealth and National cultural heritage value and significance.

The Island retains an outstanding and unique, geographically and functionally related ensemble of elements. Its layout, buildings, landscape elements, works, machinery and archaeological resources together reflect, illustrate and embody its former use and premier strategic role in Australia’s maritime, industrial and Defence history. It demonstrates the changes to maritime and heavy industrial processes and activities in Australia from the mid-nineteenth century. All elements contribute to the heritage value of Cockatoo Island as a whole and have heritage value and significance in their own right.

Cockatoo Island’s current layout and street pattern, the two sandstone docks in their dramatic, created escarpment setting, reclaimed waterside ‘working platforms’, and the form and previous function of most of its buildings and landscapes, in particular, are testimony to the physical dominance and influence of the long period of dockyard industrial, maritime and Defence uses. This physical dominance is the surviving result of the long term national, international and State and Federal Government investment in, and understanding of, the economic and strategic importance of Cockatoo Island’s dockyard, industrial, maritime and Defence uses for Australia.

Parallel with, and related to, its premier position in Australia’s dockyard, industrial, maritime and Defence history, Cockatoo Island operated as an engineering enterprise which developed and implemented standards of excellence which set best practice benchmarks throughout the country. It was Australia’s largest post-World War I Commonwealth employer, and the complexity of its union and guild membership, and the history of its demarcation and industrial disputes, catalysed the Federal Government to establish the first Federal wage and conditions award in Australia and apply it to the Island. The Federal award established to consolidate and organise Cockatoo Island was the model for many subsequent Federal awards which have operated alongside various state award systems in Australia until very recently.

Cockatoo Island’s dockyard, industrial, maritime and Defence use history reflects through its retained form and fabric, the Federalisation of previous state activities and enterprises, an occurrence that was experienced throughout Australia after Federation.

Formerly state land and the location of mixed state/ private activities; the island was resumed by the Commonwealth under emergency provisions in a time of national need.

This was due to its strategic location, established uses, valuable improvements and skilled labour force. The Commonwealth retained its ownership of those enterprises following the World War I and, by that retention, ensured it had the primary and central determining role in large engineering and maritime industries in Australia throughout the twentieth century. Retaining that primacy was an essential part of ensuring Australia’s defence needs were properly met according to Commonwealth, not state or private, priorities. This priority status became critical during the Pacific War effort from 1942, when Cockatoo Island was used to repair and re-fit various ships and vessels for the RAN, Royal Navy and the US and was, at different times, the location for the construction of HMAS Sydney and HMAS Melbourne.

Cockatoo Island’s dockyard, industrial, maritime and Defence uses were developed for the nation and in the national interest and were of vital importance to Australia for over 100 years. The surviving elements of those uses on the Island today, in particular the docks, remnant equipment, warehouse and industrial buildings and a range of cranes, wharves, slipways and jetties which illustrate the materials, construction techniques and technical skills employed in the construction of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities, remain important to Australia as an integral and irreplaceable part of its national cultural heritage.

When listing a place on the Commonwealth and National Heritage List, the Australian Heritage Council makes an assessment of the place and advises of the values that the place holds. Places on the National list have demonstrated outstanding heritage values against one or more of the criteria; places on the Commonwealth Heritage List are places managed by the Commonwealth and been found to have significant heritage values against one or more criteria.

The following table shows how the attributes of the place – either tangibly in the physical fabric or intangibly in the associations and uses – make up the National and Commonwealth Heritage listed values of Cockatoo Island. The text is taken from the citations published by the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts at the time of listings.

National Heritage Listed Values | Commonwealth Heritage Listed Values |

|

Criterion a: Events, Processes Cockatoo Island is a convict industrial settlement and pre and post Federation shipbuilding complex. It is important in the course of Australia’s cultural history for its use as a place of hard labour, secondary punishment, and for public works, namely its history and contributions to the nation as a dockyard. Fitzroy Dock is outstanding as the only remaining dry dock built using convict and prisoner labour and it is one of the largest convict-era public works surviving in Sydney. The dock was the earliest graving dock commenced in Australia and was one of the largest engineering projects competed in Australia at that time. Convicts excavated 580,000 cubic feet of rock creating 45 foot (15m) sandstone cliffs that extended around the site just to prepare the area for the dock, a huge technical achievement in itself. The dockyard’s lengthy 134 years of operation and its significance during both world wars, and in Australia’s naval development and service as the Commonwealth dockyard, all contribute to its outstanding value to the nation. It is the only surviving example of a 19th century dockyard in Australia to retain some of the original service buildings including the pump house and machine shop. The powerhouse, constructed in 1918, contains the most extensive collection of early Australian electrical, hydraulic power and pumping equipment in Australia. The surviving fabric relating to convict administration which includes; the prisoners’ barracks, hospital, mess hall, military guard and officers’ room, free overseers’ quarters and the superintendent’s cottage. Evidence of convict hard labour includes the sandstone buildings, quarried cliffs, the underground silos and the Fitzroy Dock. Cockatoo Island’s dockyard, through its contribution to Australia’s naval and maritime history, demonstrates outstanding significance to the nation. Fitzroy Dock is the oldest surviving dry dock in Australia operating continuously for over 134 years (1857-1991). The dockyard has direct associations with the convict era, Australia’s naval relationship with its allies (particularly Britain during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) and Australia’s naval development, especially during the First and Second World Wars. Cockatoo Island’s development into Australia’s primary shipbuilding facility and Australia’s first Naval Dockyard for the RAN (1913-1921) further demonstrates its outstanding importance in the course of Australia’s history. | Criterion a: Events, Processes Cockatoo Island is important for its association with the administration of Governor Gipps who was responsible for the establishment on the Island of an Imperially funded prison for convicts withdrawn from Norfolk Island in the 1840s. The establishment of maritime activities during the 1840s culminating in the construction of Fitzroy Dock 1851-57 under Gother Kerr Mann, one of Australia's foremost nineteenth century engineers; and the construction of twelve in-ground grain silos following a government order that provision would be made to store 10,000 bushels of grain on the island. The subsequent development of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities has clearly been in response to Federation in 1901, when the New South Wales government took over management of the island; the formation of the Royal Australian Navy in 1911; and the Commonwealth Government's purchase of the island in 1913. The first steel warship built in Australia, HMAS Heron, was completed on the island in 1916. During World War Two Cockatoo Island became the primary shipbuilding and dockyard facility in the Pacific following the fall of Singapore. Post war development of the facility reflects the importance of the island facility to the Commonwealth Government.

|

Criterion b: Rarity N/A | Criterion b: Rarity Cockatoo Island is the only surviving Imperial convict public works establishment in New South Wales. Individual elements of the convict Public Works Department period include the rock cut grain silos, the Prisoners Barracks and Mess Hall 1839-42, the Military Guard House, the Military Officers Quarters and Biloela House c1841. The range of elements associated with the shipbuilding and dockyard facility date from the 1850s and include items of remnant equipment, warehouse and industrial buildings and a range of cranes, wharves, slipways and jetties which illustrate the materials, construction techniques and technical skills employed in the construction of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities over 140 years. Individual elements within the dockyard facility include Fitzroy Dock and Caisson 1851-57, Sutherland Dock 1882-90 the Powerhouse 1918, the Engineer's and Blacksmith's Shop c1853 and the former pump building for Fitzroy Dock.

|

Criterion c: Research There has been considerable archaeological investigation on Cockatoo Island by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust. This has indicated that it has significant research potential in terms of enhancing the knowledge of the operation of a convict industrial site and a long running dockyard. The surviving archaeological elements of now demolished or obscured structures and functions of the dockyard, in particular the remains of the docks, equipment, warehouse and industrial buildings and a range of cranes, wharves, slipways and jetties, have potential to illustrate and reveal the materials, construction techniques and technical skills employed in the construction of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities that are no longer available through other sources in Australia. The archaeological resources also have importance in demonstrating changes to maritime and heavy industrial processes and activities in Australia from the mid- nineteenth century. The dockyard contains the earliest, most extensive and most varied record of shipbuilding, both commercial and naval, in Australia. This is supported by extensive documentary evidence in the National Archives. | Criterion c: Research N/A |